When I saw that the Classic TV Blog Association was having a blogathon about horror movie hosts, I knew I would have to get involved. The whole reason this blog exists is because of a horror movie host.

Let me transport you to a long-ago time in the early 1970s. TV stations stopped broadcasting at 2 or 3 in the morning. Cable TV was almost unheard of. Infomercials did not exist. In a big market, there were maybe 5 or 6 stations that you could watch. In the evening, after the news, you could either watch Johnny Carson or an old movie. That’s about all there was.

In those days, we didn’t have the cultural illiteracy about old films that we have today. Films were literally suffused into the air. We saw them all the time. It was nothing to see a film 30 or 40 years old, even in prime time. Black and white? No problem. We knew the Marx Brothers, WC Fields, Bob Hope, Bing Crosby, Boris Karloff.

Since films were so commonplace, there was some need for brand recognition. In the 50s, when Screen Gems released the first package of Shock Theater to television stations, someone hit on the bright idea of having a horror film host. I don’t know who it was. Someone will tell you it was Vampira, others will say it was someone else. It doesn’t really matter.

By the 1960s, almost every market had one. In Indianapolis, my home town, it was Sammy Terry. (You get the joke? It’s a pun on “cemetery.” OK, subtle it isn’t.) By the mid-70s, most of these had died out, but a few survived. Elvira and Svengoolie are two of the more known ones that have made it all these years.

Sammy Terry worked for WTTV, our local independent station. WTTV was something of an anomaly. It was technically a Bloomington station (about an hour south of Indianapolis), but they sneaked the transmitter northward to hit Indy. That could be the subject of a blog entry in itself. WTTV’s transmitter never worked quite right. There was always snow in the picture, in a predictable pattern. As a kid, I always suspected that it was my dad’s makeshift antenna that didn’t work, but when we got cable, I noticed that WTTV still didn’t come in quite right!

In those days, a TV section came every week in the local newspaper. It was important. TV wasn’t endlessly repeated, and there was no way to record it to watch later. If a movie or a show came on that you wanted to see, you’d have to schedule your life around it. WTTV, lacking both ratings and network affiliation, was like a window into the past, using outdated equipment and techniques well after the other stations had moved on.

One day, I was scanning that section and I saw that Sammy Terry was running the 1931 Frankenstein with Colin Clive and Boris Karloff. Now, in those days they marked all the black and white shows with a B/W sign. Just why they did it, I didn’t know, but at least you knew if a movie was black and white or color.

I noticed that Frankenstein was not listed as a black and white program! Could it be? Did they even have color film in 1931? I had no idea. The whole concept fascinated me. Luckily, I had someone to ask.

My grandmother was staying with us at the time. She was profoundly overweight, in ill health, and she had cataracts that needed surgery. In those days, cataract surgery was a big deal. You had the surgery and it took 6 weeks to recover, and there were all sorts of problems with it. Today you’re in and out and stapled in half an hour.

Grandma was not able to live by herself (which she normally did) during the recovery period. I knew if anyone would know about color films of the time, she would. She and I were really the only people in the family interested in the arts and movies. Grandma loved the movies.

She’d seen Frankenstein, but she couldn’t remember if it was in color. I asked her if it could have been in color. She said it was possible, because there were some early color processes at the time, but she didn’t remember.

Well, that was all I needed. I went to ask my mom if I could stay up and watch Frankenstein that weekend.

Well, mom was harried. She was under a lot of stress taking care of grandma, and she did one of her typical stall tactics. “Well see,” she said. “If you behave.”

This is code for NO.

In all honesty, I can understand where she was coming from. It was on late, and she didn’t want to deal with all that hassle, and worse yet, I was a sensitive kid who scared easily. The idea of me staying up late was ridiculous. She knew I’d have a fit if she outright said no, so she tried to stall me.

It didn’t work.

I behaved myself admirably all week. I wasn’t going to give her an out. I was planning to shove it back in her face on Friday night. And that didn’t work either.

“Eric, you have to go to bed. It’s late, and I don’t want you staying up that late. You’ve never done it before.”

“You said I could if I behave, and I did.”

I knew the battle was lost, but intervention was around the corner in the form of my grandmother.

“Sister,” she said (she often called mom “sister” because she is part of a set of twins.) “I heard you tell Eric if he behaved that he’d get to stay up. He’s been talking about this all week. You should let him see it.”

“Mother,” countered my own mother, “I need to get to bed. I can’t stay up with him and watch it.”

“That’s fine,” Grandma said. “I’ll stay up with him.”

Remember, I said that grandma was the only other person in the family who really “got” movies. That was great.

Mom reluctantly agreed, laid a lot of ground rules, but the hour was late and she was tired. She didn’t have the energy to fight. HAHA! It was going to work.

Grandma sat on our green couch and cautioned me that if I got overly upset about this then she’d send me off to bed and that would be it. She folded her hands over her giant belly and waited for the movie to start.

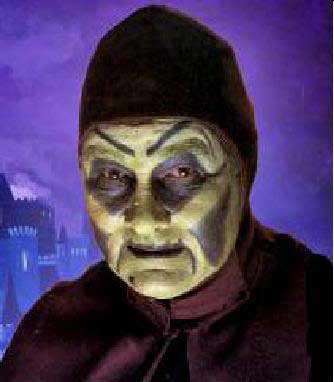

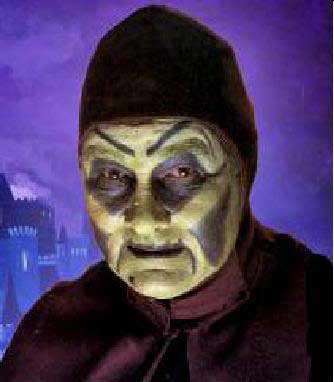

I think I had seen parts of the Sammy Terry intro before, because it looked a little familiar. Sammy wore a cowl and was made up with greasepaint, looking a bit like Conrad Veidt in The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari. Played by local performer Bob Carter, there was always something avuncular and silly about Sammy, and he didn’t scare me at all.

I still remember this after all these years. I’d worked myself into a tizzy about seeing this, wondering if it could actually be color. I knew the time was nigh. Sammy (or someone) had fashioned a poster for Frankenstein, done very cheesily in a hand-drawn way. At the bottom someone had penciled in this tag line: “In Horro-Color!”

WOW! Could it be?

It was my first Sammy Terry intro and I just wished he’d shut up and run the movie. I don’t think my grandmother even lasted through the first 10 minutes of the show. By the time the film started, she was gently snoring, with her hands still folded in front of her.

Well, as you probably know, the film was in black and white after all. (Of course, this sparked a lasting level of curiosity in me, because I have a long demonstration about the history of color in the movies that’s one of my most popular shows.) I eagerly sat through the movie, color or not. I was delighted. The film had a weird rustic feel that I found to be really cool. I sat quietly through the end of the picture, woke grandma up, and we both went to bed.

She created a monster.

I was hooked. I wanted to keep watching Sammy Terry and see more of those films. I had to. Grandma gamely stayed with me on most of them, still usually falling asleep. She had one eye done, 6 weeks recovery, and another eye, 6 more weeks recovery. By that time, I was a hopeless addict. She went home, but I kept watching Sammy.

I discovered that my parents didn’t care too much as long as I didn’t make a lot of noise to wake them up.

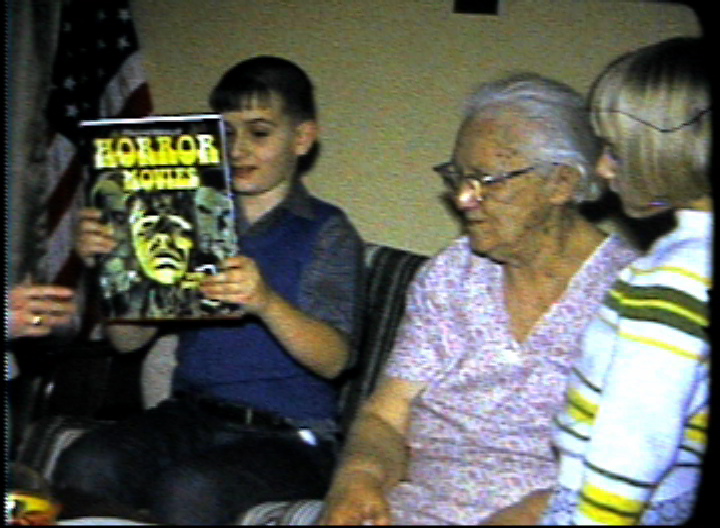

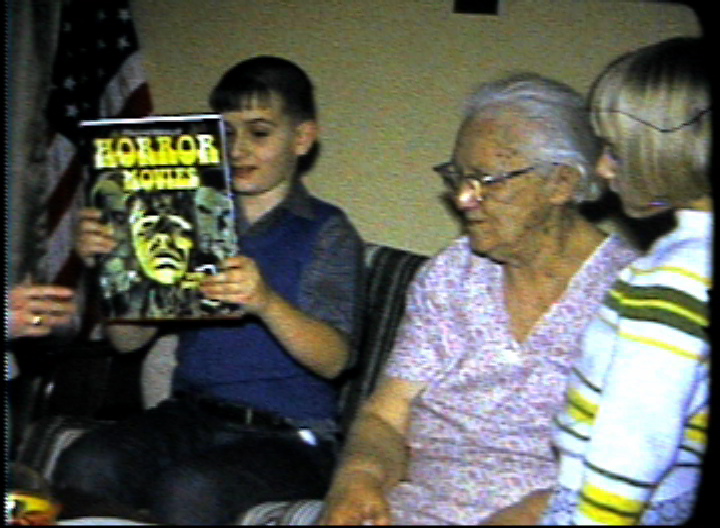

I discovered that the local bookstore had a new book by film historian Denis Gifford that gave a great history of these movies. Mom had picked it out, and she had it wrapped “From Grandma” for Christmas that year. I recently found the 8mm home movie of that Christmas, showing me unwrapping the present. I still have the book.

That’s me (on the left) with my grandmother and sister, Christmas 1973

I seldom missed Sammy Terry, and I went on to catch the Saturday night offering on WTTV, which was called Science Fiction Theater. In the summertime, WTTV had another film host showing Summer Film Festival which consisted of more mainstream films. I loved it too. WISH Channel 8 had host Dave Smith with another show called When Movies Were Movies. I loved it too.

It got so that in the summer I was up until 3am most every night.

Sammy was still a special favorite. I loved his silly jokes and weird introductions, his hairy spider (named George) who interrupted the proceedings periodically. I even loved the stupid gaffes that we’d never see today. The Sunday paper listed one film as Sammy’s show for the week, but the Friday paper listed another film. That night, Sammy’s intros were for the film in the Sunday paper, but they ran the film listed in the Friday paper! OOPS.

My grandmother died in 1975. She was a special woman and I miss her to this very day.

WTTV canceled Sammy Terry in about 1976. I was outraged. I started a petition to put him back on the air. But the times had changed and they didn’t want to go back.

They finally relented and brought him back in the early 80s. The film package wasn’t as good as it had been, but it was still fun to see Sammy back again. There were fewer Karloff and Lugosi pictures and more gut-laden Hammer films.

Then, in the mid-80s the world changed again. When cable became widespread, the studios discovered that they could make more money from a cable film showing than from the local stations, so they pulled all the old films. As historian Jim Neibaur has said, it was like they decided to make one station the repository for all the old films and they filled the rest with infomercials.

Sammy Terry was gone. Bob Carter continued to play the character at live shows and in the occasional special. I met him a few times. He ran a music store close to where I lived. Seemed like a nice guy, but it was never more than a passing encounter.

Mr. Carter has been in ill health for the past few years, so he has not been so active. His son is carrying on the Sammy Terry tradition. I haven’t seen him yet, but I wish him well.

Of course, I started to miss that late-night experience I had so loved. I collected videotapes of my favorite movies. Then 16mm film. Then 35mm film.

I’m not on TV (not yet, at least), but I carry film projectors to run film shows wherever I’m wanted. I got to run a movie with WTTV’s cartoon show host, Cowboy Bob, and WFBM’s Three Stooges host, Harlow Hickenlooper. It was freezing cold, and with the two of them there, including me and an assistant, I think we had 6 people in the audience. Oh, well. I had fun anyway.

And that still doesn’t bring the story to a close.

One of the things that dogs me about new technology is how we throw out the whole of the old to embrace the new. We often don’t fully appreciate the magic of what we had until it’s gone.

The old horror hosts and the movie hosts in general helped us appreciate films made before we were born. It was just part of who we were. Now, all you have to do is channel hop over Turner Classic Movies and you’ll never see them at all.

It’s no disrespect to Robert Osborne or Leonard Maltin to say that they’re not the same as the guys from the old days. They are preaching to the converted. You don’t watch them unless you specifically want to see an old film. There’s nothing wrong with that, but sometimes we look at old films as either obsolete relics or unapproachable HIGH ART.

There is little appreciation for film as an art form today. That’s why I created Dr. Film. It’s a deliberate throwback to the old hosted-film format. Dr. Film isn’t specifically for horror films, although we will show them. It’s got the poverty-induced sets and goofy jokes that all the hosted-film shows had.

What’s different about Dr. Film is that its purpose is to subtly educate (and I hope it is very subtle). I hope it’s just strange enough to catch an errant viewer asking, “What the heck is THIS?” before he flips the remote one more time.

No, this doesn’t mean I regard the new Sammy Terry as competition, because he’s not doing the same thing. Nor do I regard Svengoolie or Elvira as competition. I embrace them all (I’d particularly like to embrace Elvira in that tight dress, but I digress.)

I always think that a rising tide floats all boats. And I think that the movie host is something we’ve lost and that needs to return. I think we all miss them, even if we don’t know it.

Dr. Film isn’t really competition for anyone, because the show hasn’t made it to the airwaves. In all honesty, it probably never will. But I’m still in there trying, because I’m trying to save a part of our past that I miss.

Instead of tilting at windmills, I’m saving film. I might just as well be trying to save Fizzies, Burger Chef, and handmade chocolate sodas. Hey, maybe it’s a lost cause, but someone has to do it.