Category: Dr. Film’s Pocket Rants

Current (10/26/20) Kongo Status

I cover a lot of this on my Facebook page, but not all of it. I know a lot of you don’t see Facebook, so here is the detailed, long-winded, accurate rundown of what is happening with King of the Kongo:

I now have two assistants helping me to get this done and I am spending grant money to get them faster machines. The rendering was so slow on the machine I had that I thought it was worth spending the grant money on the faster systems and getting some help. We’re really going full smoke here: 12-core, 3.46Gz, 128GB RAM. Even then some of it is slow.

Just so you understand some of the jargon here: each chapter is two reels (except for Chapter 1, which is three reels). R1 is Reel 1, R2 is Reel 2. A slug is a piece of black leader inserted into the film. This was done to repair film breaks in order to maintain the length of the picture, because otherwise the sound would get off sync.

Chapter 9:

I started with this chapter since it looked the worst of any material I have seen so far, and I had to devise economical ways of addressing the decomposition in it.

R1: (see video)

There was fairly heavy decomposition all through this and there were three or four shots that looked awful. These have been improved immensely. One shot was completely decomposed and was replaced from 16mm.

R2: In progress. The negative has a fair amount of decomposition in it but not as bad as R1. Fortunately, unlike R1, we have a backup R2 from an edited print. It’s been stabilized and graded. The gorilla assault at the end of the reel may have to be switched out with the print if we have it.

Chapter 10:

I did this chapter second because we only have a print. There are several slugs in this one. The nitrate print was weaving to the left and right in the scanner (it was shrinking), and is presenting a stabilization problem. I’ve run 5 passes to stabilize it so far and it’s about there.

R1:

There were two sequences that were edited out of the print. The first was the entire gorilla assault that ends Chapter 9. It’s unfair to replace this with the footage from Chapter 9 because this is shot with a different camera and is edited differently. I replaced the footage from the National Film Preservation Foundation grant project in which I restored Chapter 10 from 16mm. The footage isn’t that great, but it’s all there, and we’re talking about a minute’s worth or so. There’s another sequence that was also cut, that of Lafe McKee and Harry Todd confronting a dinosaur, and I replaced that from 16mm as well.

I may try some frame interpolation to get the missing frames back (ironically, this print is the source print from my 16mm, and the missing frames in it are also missing in this 35mm!), and I am also going to try to remove some of the uglier artifacts toward the end of the reel. Someone put cue marks in the reel so they could do a changeover and the marks are ugly and historically incorrect. Before you ask, the missing frames were lost in during projection in 1929 and the edited sequences (which are in my 16mm) were cut for stock footage many years later. The history of these prints is archaeology in itself.

R2:

This reel is in better shape (considering splices) and worse shape (considering projector wear). I’ve done a fair amount of cleanup and stabilization on it already. Steve Stanchfield is working on de-flickering it for me. I’ll take all the help I can get!

Chapter 8:

We have a negative for R2 and a print for R1 and R2. The negative has not been scanned yet, so is in unknown condition. The print is in decent shape with a few splices and slugs. We have sound for R2.

The cliffhanger in R2 was edited out, and, interestingly, was floating around unidentified in the collection. It was run at the Library of Congress’ Mostly Lost convention a few years ago, and I identified it as either the cliffhanger of Chapter 8 or the resolution in Chapter 9. Turns out it is Chapter 8 and will be reunited with the source print. I’m receiving a copy of the scan today to get it restored.

Chapter 8 has been contrast corrected and is awaiting stabilization.

Chapter 7:

R1 has been contrast corrected and is awaiting stabilization. We have also found a “spare R1” that is proof that there was a silent version of Kongo. I have yet to see a contemporaneous ad that doesn’t advertise this being “in sound.”

Inspection of the rest of the prints:

At this point, we still have no material on Chapter 1,2 and 3. This is due to COVID and the schedule at Library of Congress. I haven’t engaged in much work on any other chapters. Chapter 5 and 6 have tinting and that will be reproduced.

SOUND:

We have complete sound for Chapter 5,6, and 10. We have one reel each for Chapter 4,7,8,9. That means we have no sound for Chap 1,2,3 at all and only half the sound for Chapters 4,7,8,9. We have the original scripts for this.

David Wood has done restoration work on 5,6,10 and also a nearly finished Chap 9, R1. We’re doing some more experiments on cleaning this up a little better.

I have been saying I hope to get this out by end of 2020. It won’t be finished by then, but I’m trying. I’ve been working on this since late October 2019 and so far have gotten just 5 reels with any significant progress. That sounds worse than it is, because a lot of that time was upgrading computers, training people how to use software, and mostly figuring out how I could do this technically!

On Marvel and Snobbery

First off, let’s take this on a micro level. On the level of individuals and individual taste.

There’s been a lot of huff lately because Martin Scorsese has been on record saying that he thinks Marvel movies “aren’t cinema.” Francis Ford Coppola has backed him up. The backlash is that people are now saying that anyone who doesn’t like the Marvel films is a snob.

Wait a second. We’re all snobs. And we have to be. It’s self-defense.

All you have to do is scroll through Netflix and see the endless movies that are on there, and realize that it represents only a fraction of the movies produced and the ones that are available. If you sat and watched them all day, you’d never get to the end of it. You have to be your own filter.

You have to say, “I like this kind of film, and I don’t like that kind of film.” It’s that simple. It’s the way we eliminate things. It’s stereotyping, and it’s inherently unfair. And it’s snobbish.

And before you say, “Stereotyping is always bad,” remember that stereotyping has probably saved your life today. We all do it. We do it to save time and energy. You’re out driving and you think, “that van driver is an idiot. He’s weaving badly,” and you avoid him. A minute later and he veers into your lane, and you were right. You stereotyped him as an idiot, it was probably unfair, and you saved your life because of it. You may not have even been aware of it. Movies are the same way.

I filter movies in the same sort of way, and you probably do, too. I hate seeing the same thing over and over again. I hate getting 2/3 of the way through a movie and knowing how it’s going to end. You know the drill:

The killer monster isn’t REALLY dead, and he’s coming back for you…

The guy we thought was the cattle rustler isn’t really the cattle rustler, and the bad guy is actually a good guy.

James Bond gets out of a deadly situation because the bad guy comes up with some convoluted plan instead of JUST SHOOTING HIM.

The gangster is an emotionally constipated guy who is ruthless and deadly, and eventually causes a violent gang war in the last act of the film…

I hate movies like this. If I think they’re going to be completely predictable, I will skip them. My definition of a good movie is something that has me guessing by the last act. Charlie Kaufman films are good movies in my book. Sometimes I don’t even know what the hell they’re about even after I’ve left the theater.

So I have to confess that I’m not a big fan of Marvel Comics movies. They’re cookie-cutter movies, following the rules of Save the Cat, and I’d rather skip them. I know people will yell at me about this and tell me that I’ve never seen any of them, so how would I know?

Well, that’s kinda the point. I actually have seen some of them, in parts. I saw part of one of the Spider-Man movies by Sam Raimi. I like Raimi as a filmmaker, so I thought I’d give it a shot. The movie was not only predictable, but the CGI effects were idiotic and ruined the entire picture. They were so idiotic that I thought the animation in the old Filmation Spiderman shows was superior. That’s not a compliment to Filmation.

And now, they’ve rebooted it, what, twice? No, thanks. I assume the CGI is better now, but it needs to be a lot better and the plots a lot more interesting before I’m in.

Have I always been against superheroes? Well, no. I cut my teeth on the old George Reeves Superman shows, and I loved the old Batman shows with Adam West. Those were done in the accepted old way where we said, “Hey, these are comics, we can’t take it seriously, and so let’s be silly with it.” And the serious comic fans hated that (the Batman series much more so than the Superman series.)

In 1978, there was a reboot of Superman with Christopher Reeve. Reeve was a magnificent actor, and he did a lot with the part we hadn’t seen before. Moreover, they took the tone somewhat more seriously—it played more like a James Bond picture. There’s no coincidence there: the screenwriter was Tom Mankiewicz, who had written some of the Bond pictures in the early 70s.

It wasn’t until 1989 that the superhero movies piqued my interest. It was Tim Burton’s reboot of the Batman character. It wasn’t patterned after the comics, but it was reworked as a film noir/German Expressionist kind of film. It was a complete departure from what had been done before. Sign me up. Let’s give it a shot. I wasn’t the only one: lines were around the block just to see the trailer for this one. We all thought it would be a joke with comedic actor Michael Keaton in the lead, and we were wrong.

In 1992, he followed it up with a better version of the story, making it even MORE German Expressionistic (I’m a sucker for that), and we had a character named after 1920s German actor Max Schreck. I’m on board. But Burton’s vision was too dark for Warners, so they hired director Joel Schumacher to take over, and he camped it up again. Yawn.

Since then, the now-rebooted-twice DC universe has been in a race to be as dark as possible and as kid-unfriendly as it can be. The dark tone gets ridiculous because it’s so overdone. I generally like Christopher Nolan’s movies, but his Batman epics are, in my opinion, unwatchable. Too much cut-cut-cut spastic editing, too dark, and no characterization. Not interesting.

So I’ve written off both the DC universe and the Marvel universe. I guess the reasons are slightly different, but I still don’t care.

But that’s OK. I write off lots of stuff. I think Martin Scorsese is a great director, but I don’t like gory violence in movies, and I think gangster movies are so clichéd that I can’t stand them. Scorsese’s non-gangster movies (like Hugo or The Aviator) are excellent, but once I see DeNiro in the cast, I start to wonder if I want to see it.

I know a lot of people love gangster movies, but I have always thought the best one was The Public Enemy in 1931, which set the limits for every one to follow, and still has the most brutal ending of any gangster movie I’ve ever seen (even though they couldn’t show spurting guts in color, it’s still brutal.)

The pattern is always the same: Young upstart takes over the underworld, he’s emotionally constipated, can’t relate to anyone, very cold, and he fights, claws, and kills his way to the top. At the end, there’s a gang war and he’s either triumphant or is killed, depending on this slight variation.

The Godfather films are a nicely made version of this, and we have two characters in the films who play this plot out. Then there’s Goodfellas and Casino and The Departed and… I didn’t watch them. If they’re substantially different, then someone tell me and I’ll skip past the spurting guts.

Someone told me about The Sopranos and I thought, WOW, this must be finally the new wrinkle in the gangster stories I’ve hoped for. With the introduction of the psychologist character and a gangster who has emotional issues, I thought it might be something new. It was, but only for a while. They finally decided that Tony Soprano was a sociopath and was going to keep killing people anyway. And that sucked, because why would a sociopath seek counseling? They think they’re better than everyone else from the start… they would never talk to a counselor. I skipped the last couple of seasons.

So, if you’re keeping score, I’ve just written off the Marvel universe, the DC universe, and a lot of Scorsese and Coppola. I must be a super snob. I’ve spent about 1300 words defending my positions for disliking all these films and I’m now ready to completely refute my argument. Well, maybe not refute it, but I’ll definitely reframe it.

Because now, we’re going to transfer ourselves into the macro universe. The big picture, where we talk about cinema itself, the audience, and the direction of art. Not about individual preferences.

It doesn’t matter what I think.

It doesn’t matter what you think.

It doesn’t particularly matter what Scorsese and Coppola think.

Here’s the problem: whether you like the superhero films or not, they are cinema. They may be cinema we don’t like, but they’re cinema. The problem is that the superhero movies are crowding out everything else from theaters. This is by design. They see teenagers as ones who will buy merchandise (they make more money from that than tickets), and they see anyone outside that demographic as irrelevant. It is by design that I’m turned off by too many superhero movies.

I spoofed this in one of my podcasts where Dr. Film went to the multiplex to see Stan and Ollie and everything playing there was a superhero movie. (Incidentally, the reason I positioned the Dr. Film character as a film superhero was just to spoof this kind of thing. The podcast episode has me turning into a superhero to complain about superheroes. It’s a joke on a joke. Sorry I had to explain that!)

And this points up a bigger problem: what the hell is the world of cinema coming to when Martin Scorsese can barely get a film into the multiplex? Coppola can’t do it, either.

We’re at a point were Netflix is controlling the world of movies (they financed Scorsese’s latest picture), and Netflix has yet to decide whether they’re only a streaming service or a theatrical distributor AND a streaming service.

Meryl Streep has complained that we’ve catered films to teenage boys because they are the most reliable audience for theatrical movie. She’s right, and gee whiz, what did we get? Superhero movies.

We don’t have a wide audience going to movies because we’re catering to teens. The teens don’t know how to behave in movies, so they’re rude. They drive out the older folks. Add that to badly maintained projectors and theaters, and we have a microcosm of what’s wrong with movies today.

I don’t hate superhero movies. I don’t particularly want to see them, and that’s by design. The trouble is that we need variety back in theaters. We need the voices of Scorsese and Coppola. Hell, even Roger Corman. I’d rather see them come back than one more reboot of Spider-Man.

Aaaaand, I answer your questions…

Q1: It’s been a long time since you’ve written a blog. You’re still on Facebook periodically. What are you doing?

I’ve been working on things. I’m hoping to get King of the Kongo going someday soon, but it’s been a problem. I’m working on some other projects too. I’ve hit a ton of roadblocks, and I’m even hitting some now. It’s been frustrating. (If you’re a newbie, King of the Kongo is a project I’ve been working on since 2011. It’s the first sound serial, and I restored three chapters of it before I discovered that there is better material out there and it can be upgraded.)

Q2: What’s the deal with King of the Kongo? Why not just release what you have?

I was on the cusp of doing just that last year when Steve Stanchfield convinced me to make one last run at the 35mm. There’s a 35mm at the Library of Congress, which is kind of a mess, but mostly complete. I’ve looked at it and it’s really nice for the most part. There’s even a lot of original negative in it. The 35mm has what’s called a donor restriction on it, meaning that the donor regulates who has access to it, even though it’s held at the Library. Confusing? Welcome to my world.

Q3: Well, we’re your supporters. Do a Kickstarter and get it out there.

It’s not that simple. Doing a quick budget run on it made me realize that it was going to cost more than I could raise on Kickstarter. We needed to pay the donor at Library of Congress a large access fee and that was a bugaboo. She named a fee and then I had to scramble to find ways to raise that money.

Q4: Did you find some?

Yes, the Efroymson Fund very kindly awarded me a grant last year, but then I had trouble raising the donor and then I’ve had trouble with some of the intricacies at the Library of Congress. They’re great, but it’s a process. There’s been lot of red tape I’ve had to get through in order even to start this. I was considering starting another Kickstarter to raise even MORE money.

Q5: Are you going to?

Not right now. It’s not just super easy to do this work. You have to get a lot of people on board, you have to get grant agencies on board, etc. There’s no way that I could recover the production costs of King of the Kongo without getting grant money or Kickstarter money to do it. It just doesn’t make sense. If some of the arrangements I’ve made fall through, then yes, I will do another Kickstarter, but we’ll see.

Q6: Well, there’s another organization that’s wanting to release it, and they’ve been putting out flyers…

Yes, I know about that. It’s one of those things that bugs me. I would have liked to work with these guys, but they seem to think I’m the bad guy for some reason, and that I want lots of money. I can’t imagine why anyone would think I want lots of money for a project like this, but they seem to. It’s sad, really.

Q7: Well, why not pool resources and work with them, just swallow hard and do it for the good of film preservation?

I’d like to, and I did try, but the response I got was being trashed personally and professionally in letters and public forums. I cut people a wide swath, and I don’t care if you trash me personally to my face, but when you take it public, and you damage my reputation in ways that cost me money, I draw the line. I actually get criticism for being TOO WILLING to work with some people, but these guys, no. I can’t. I honestly wish things were different.

Q8: So when it Kongo coming out?

I have no idea. It will come out when it comes out. I’m right now waiting for some scans to start trickling in. This has become a really epic project that seems to have a life of its own. The good news is that, unless we find more sound, this will be probably close to the end of it, because we found a lot of original negative.

Q9: What other projects are you working on?

Well, I was trying to get a disc out with some of my really rare animation films on it. I’ve been working on that since the first of the year. The project seems to have stalled and I’m not sure when it will come out, if at all.

Q10: Kickstarter?

Maybe. But I can’t do a Kickstarter until I know that I can actually do this project. Otherwise, I risk raising funds for a project I’m not sure I can deliver.

Q11: Anything else?

Yes, I’m working on getting some Lupino Lane films ready to release. I’ve been working on some scans I got from Library of Congress. Thad Komorowski has been doing some work for me even this week on it. I’ve got to get some technical hurdles fixed on this one before it comes out, too. Otherwise, it won’t be good enough.

Q12: Why not just release what you’ve got?

I may have to, but I really try to make these things look as nice as possible. One of the problems I have is that I’m willing to take on projects that are a little less commercial and where mint condition materials do not survive. (I’m attracted to these projects, because I know if I don’t do them, then no one else will.) This opens me up for criticism about doing sub-par work. The Lupino Lane films, by and large, survive in choppy 16mm 1920s Kodascopes and copies of choppy 1920s Kodascopes. They will never look fantastic, but they should look a lot better than they do.

Q13: Why do you care about the criticism? Just do the work!

I have to care about it somewhat, because people jump in and trash you and then you have the reputation for turning in 3rd-rate work, which hurts your sales. In a lot of cases that I work on, perfection isn’t an option, and it’s not even close to an option. Little Orphant Annie has sections in it that look kinda soft. They always will. There are a couple of shots where I have to cut to inferior material right in the middle of a scene, because footage was missing in every other print. But it’s complete and in order, and I’m proud that we were able to get that accomplished. It’s as good as that film can look now. I still have 400 copies of Annie sitting in my living room and I can use the space, so I need to worry about the criticism a little bit.

Q14: Why do you do a long blog occasionally instead of what Seth Godin says, doing a short blog often?

Seth Godin would faint at my marketing practices. I write blogs when I can (right now I’m inspecting a print of The Front Page as I write this), and it’s in chunks. I also have a visceral reaction against the flippant, now, now, now, short, short, short mentality we’ve developed as a culture. I like to take my time and develop things. That’s why I love the folks who’ve read this far. Thank you. (BTW, you can listen to the podcast and hear us spoof ourselves and Seth Godin a little bit.)

Q15: Speaking of Annie, why haven’t you sold it to TCM? Wouldn’t that help you?

I don’t think it’s going to happen, guys. It was in the hopper a bit over a year ago, but it dropped off the radar when Filmstruck died. I’d talked to them about a number of other projects, too. It was just the wrong time. And I’m not sure the right time is going to happen again. I’d like to be wrong on this.

Q16: Why haven’t you tried getting funding for King of the Kongo through TCM or releasing it through Kino?

Who says I haven’t? Kino was very positive about this project and wanted to help, but the numbers just didn’t make sense. TCM was just plain not interested. I suspect that if I can get it out there, then TCM may perk up, but right now I’m a super-niche releasing guy and I have only one major title in my hopper. I’m beneath their notice, and, frankly, I probably should be. I’ve got to get more product out there in general, and I just haven’t. (I’m not averse to going through places like Kino in general, and they released my prints of two major titles last year for their Outer Limits sets. They’ve been winning awards, too, including the Rondo and Saturn awards. However, unlike me, Kino is not just plain nuts, and they can’t go releasing projects willy-nilly that no one will buy!)

Q17: Didn’t you say something about a blu-ray of Ella Cinders and some restored footage?

Yes, it’s in the hopper. I’ve located multiple prints of the Kodascope and we should be able to create stunning material on it, and there will be no cut footage, but maybe stills. If I had a staff of 5-6 people and a budget for scanning, I’d be on that right now. There’s script for the complete film and an original score that survives. But I can’t get to it just now.

Q18: Well, we support you! We know that it would be easier to get more films out of you if you had more cash coming in. Why don’t you do a Patreon so we can support that?

I’ve been considering this, but the bugaboo I have is that I need to provide something monthly or quarterly to Patreon subscribers, and I have no idea what that would be. These things are like earthquakes. You may not have any action for years, and then suddenly everything breaks loose. If any of you have ideas on how to do a Patreon successfully and keep subscribers happy, I’d love to hear it!

I honestly love you guys for the support I’ve had. We’re in a best of times, worst of times Dickensian conundrum these days. In terms of the access and technology to present these films, it’s the best of times. In terms of the marketability of the films, it’s pretty awful. Markets are drying up faster than we can fill the void. That’s why I love you guys so much. You’ve supported my work through a failed TV pilot, into a blog and now into a weird podcast and restoration work. It’s been a wild ride!

The Romance of “Bad” Cinema

One of the things I get asked frequently is if I’ve seen the worst film ever made. The given answer, since The Golden Turkey Awards came out, is that the worst film ever made is Plan 9 from Outer Space (1959). That’s not a great picture, but the worst?

Being a film historian, I’m also supposed to know the greatest film ever made, and I don’t know what that is either. There’s no such thing as a perfect film. They all have problems. For example, the worst cutting continuity I’ve ever seen is in The Ten Commandments (1956), which is considered a classic. There are more mismatched cuts in that film than I’ve ever seen. It leaves Plan 9 in the dust, and Plan 9 isn’t very good.

I’ve often said that Plan 9 isn’t even the worst Ed Wood film. It’s not the worst Bela Lugosi film. There are films with special effects that are not as good. It’s not particularly ambitious and it manages to miss most of its goals, but it hangs together as a film.

The most charming thing about Plan 9 is the tin-eared dialogue that Ed Wood manages to infuse in the proceedings. It’s the kind of dialogue that an actor can’t read at all, even though it may look OK on the page. It forces the performances to be wooden and strange, and it makes them funnier than they should be.

(Aside: Filmmaker Larry Blamire is an ace at imitating and spoofing Ed Wood-style dialogue, and people have criticized him for it. I’ve read numerous clueless reviews that accuse his films of trying to be bad. They are not trying to be bad. They are spoofing the style of movies from the 1950s. They’re taking it a notch higher and making it funny. I can’t understand why people get this with Airplane! (1980) which spoofed the deadpan over-the-top style of airport disaster movies, but they often miss it with Blamire’s films. End long aside.)

Plan 9 is basically trying to be a mixture of The Day the Earth Stood Still and a zombie/walking dead film. It contains the dire warnings from the aliens and the ghoul trappings from other pictures. The special effects are bad, the dialogue is bad. The editing is world-class terrible, but not the worst I’ve seen. (See the article I wrote on this years ago). But the script itself isn’t too bad. The concept is OK. The actors do a decent job, although not spectacular (Mona McKinnon is a special exception… she’s awful.) The sets are passable, although they look cheap, because, well, they are.

But if you want to see a worse Ed Wood film, watch Glen or Glenda. There are large swaths of it that don’t even make sense. You could cut Bela Lugosi’s scenes out of it and never know they were gone. If you want to see a film with worse acting in it, geez, there are a lot of them. If you want to see a film with worse special effects, how about Robot Monster (1953), which has a few shots of the “space platform” that are truly laughable? Or maybe The Lost City (1935) with a few shots of a model ship that wouldn’t fool a five-year-old.

The thing I admire about Ed Wood, and I truly do admire it, is that he got these films made. He got them released. It’s a difficult thing to do that. For every one film that is made, there are a hundred that were started and not finished. For every one not finished, there are probably 10,000 that were never started. There’s a big part of me that scoffs at people who say they could have made a better film than Ed Wood. My answer is the same as what I often say when people criticize my own work: “Yes, but you didn’t.”

I’m not trying to defend Ed Wood here. His films are pretty bad, but he made it through meetings with stupid producers, financing people, editors, actors, cinematographers, lighting guys, studio renters, effects guys, and all the other people you have to deal with, and he did it. And not only did he do it, but he did it with almost no money. It’s an admirable thing that he could do it at all.

I’ve been going through the work of director Bud Pollard lately. (Full disclosure: I’m considering doing a Blu-ray of his Alice in Wonderland [1931] and the surviving footage of The Horror [1933].) Bud’s films are every bit as bad as Ed Wood’s. The acting is, in general, worse. The sound recording is worse than Wood’s. The makeup is inexcusable. The cinematography ranges from decent to terrible. But Pollard did this 25 years before Wood did, and he got all of this done when it was a lot harder technically to make a sound film at all. On one level, you’ve got to respect the achievement.

Alice is, however, still laughably bad. The lead actress has a wig that would embarrass even William Shatner… one person ran out of the room screaming when I ran it and another told me it gave him a headache. But still, Pollard got this made. For what it’s worth, The Horror or at least what survives of it, is much worse and has even more problems… and it’s not entirely clear whether that was released or not.

The bottom line is that all of these films are entertaining. They may not be classics, but they’re fun to watch. It’s enjoyable to see what these guys did with no money and how they worked with it. I respect this immensely. I love to sit through a “bad” film now and then just to see how they’re put together. It’s one of the reasons I restore things like King of the Kongo. I know no one else will touch them.

Then there are the films that are made with a cynical intent to cash in on something. The 1967 Casino Royale is a fun mess, but a misfire intended to exploit on the James Bond craze. 1950’s Rocketship XM loses points with me for being an attempt to seize the publicity around Destination: Moon. It’s a decent enough picture, though. Then there are things like Weird Science and My Science Project, both intended to ride the wave of PR that was to be generated by Real Genius (1985). Real Genius tanked because those two films preceded it into release and made everyone think it, too, was junk.

Another case in point: Bela Lugosi Meets a Brooklyn Gorilla (1951). This movie is terrible. I mean, it’s really, really terrible. Apparently, the motivation was to use these two guys (Duke Mitchell and Sammy Petrillo) who had an act imitating Dean Martin and Jerry Lewis and to put them in a faux Martin/Lewis film. The hope was that Paramount and Hal Wallis would see the film and pay to have the negative destroyed, which it wasn’t. I’ll admit that I’m not a big fan of Martin and Lewis. Their comedy seems a little desperate and forced to me, and I know it’s a minority opinion. I like the way their movies are made, and I respect the performers a lot, but I just don’t find them especially funny.

Mitchell and Petrillo, on the other hand, are painful. Petrillo looks almost like a clone of Lewis, but he’s nowhere near as talented on any level. Mitchell is a decent singer. I can give him that, but he has no comic timing at all. Poor Bela Lugosi looks sick and doesn’t understand what he’s doing in the film. Frankly, I don’t either. The bottom line is that this is a train wreck. It’s not really even entertaining. You just watch it with your mouth open.

But, for me, the bottom of the barrel are these films that should really be tons better than they are. A lot of people will tell you that Ishtar (1987) is terrible, which it isn’t. It was handled by a director (Elaine May) who was used to shooting lots of footage of ensemble players, and when she had to do that with a picture that required action and had two expensive stars in it, the movie went over budget. But still, there are a lot of laughs in Ishtar. It’s full of good moments and clever repartee.

How about The Island of Dr. Moreau (1996)? This is an awful film. With uneven special effects, and terrible performances, topped off by in incomprehensible script. The 1932 Island of Lost Souls is pretty good. The 1977 remake Island of Dr. Moreau isn’t very good, but it’s light years ahead of the 1996 version. The newer film stars a bloated Marlon Brando having an attitude attack about being in a film at all, with Val Kilmer having an attitude attack about being upstaged by Brando. The film had a troubled production history, with bickering stars and directors, finally being helmed by none less than John Frankenheimer, who should have known better. You’ve got a boatload of top talent in this film, and it adds up to a complete mess.

Another total loss: Battlefield Earth (2000). OK, this movie is awful. I suppose the special effects are decent-ish, but John Travolta and Forest Whitaker are over the top in the worst possible way. The script is a total disaster, full of improbable coincidences and plot holes you could pilot the Titanic through. Director Roger Christian has had an undistinguished career as a director (although he’s a top art director), but I get the feeling that this film was going down the tubes before they ever called him.

And ultimately, I find these less excusable than Ed Wood’s pictures. These guys had everything. Money, actors, cinematographers, screenwriters, top studios, and they still couldn’t make a decent film. You wonder what Wood could have achieved with similar funds. It certainly couldn’t have been worse, and maybe it would have been entertaining.

I’m going to be discussing a bit more about this in some upcoming blogs. It’s easy to make fun of a bad movie, but it’s really hard to make one. It’s like those painful assignments you used to get in social studies class. You’re thrown together with people who have to work in a group (in this case, it’s all the actors and behind-the-camera people you need to do the work.) If you happen to get a group of all of the smart kids, you can do well. But if you get one kid who screws up and doesn’t do his job, the whole group can look bad. Even then, sometimes the smart kids make a bad project, and the kids who sit in the back and sleep come up with a winner once in a while. You just never know.

Cinema at a Crossroads

I think we’re seeing the death of classic cinema. I really do. You’ve heard me rant about this before. We’re seeing that the only 5 great films that everyone wants to see are Casablanca, Singin’ in the Rain, Gone With the Wind, Citizen Kane, and Wizard of Oz. After that, the Godfather films are OK, and then Cinema begins with Star Wars.

I don’t know what to do about this. I don’t know what can be done. One of the main arguments, which I absolutely hate, is that these movies are no longer culturally relevant and are such relics of the past that they should no longer be seen, because no one cares. Nor should they care. The 5 movies listed above (I refer to them as the Holy Quintet) are exceptions because they have passed the cultural litmus test of history.

I hate that. I know I said that, but I wanted to accentuate that I hate it.

You can argue that TCM keeps cinema alive, and to an extent, they do. But they only keep some cinema alive, and they only have 24 hours a day. I have also complained, with some validity, that they show Casablanca too much, whereas they could show a lot of other stuff and do classic cinema a lot more service.

But then if I owned Casablanca, I’d show it a lot, too. It’s a fine picture, but it’s got to bear the burden of representing most films made before 1977.

There’s a vast array of silents (TCM only shows silents 4 times a month, at midnight on Sundays), B pictures, cartoons, serials, short comedies, and such that never get seen. That never will be seen. Stuff that’s fun, entertaining, and would even, dare I say it, “educate” people. The collectors have some, the archives have some, and the studios have some.

There’s always archive.org. I don’t like it. 90% of it is junk with terrible compression rates and bad quality. It fosters the idea that all old movies look bad. Then there’s YouTube, which, well, is pretty much the same. That’s not to mention the fact that piracy on both sites is rampant. I had to alert Kino to a site that was bootlegging Seven Chances with Bruce Lawton’s commentary and my color restoration on it. YouTube took it down, but the same guy got a new address and put it right back up. He put ads in it.

But it’s free!

Netflix isn’t the answer. Why? Because increasingly it takes movies (and I mean even recent ones) off the server and replaces them with binge-watching TV shows. They started off kinda cool, but died away quickly.

I had a lot of hope for Filmstruck (and, full disclosure, I was working on a deal to supply them with some silents and other materials), but AT&T killed it. Why? It wasn’t making enough money. (And, yes, that means that the deal is off.)

You see, no one sees classic films.

So no one watches classic films.

So no one buys Filmstruck.

So AT&T cancels it.

The saving grace about TCM is that it was stipulated in the sale to Warners that TCM had to stay on the air as a commercial-free classic film network. And that keeps it on.

This is causing me to want to ramp up a service that I’ve wanted to do for some years. I think of it as a public service, because it would provide a venue for NON-SUCKY transfers of films that TCM doesn’t show, which, let’s be honest, is about 80% of everything.

And I know you’ve heard me talk about this before, too. But I back-burnered it because I was busy with other projects, like Little Orphant Annie and King of the Kongo and the Milan High School games.

TCM has kind of the right idea with its educational program advocating The Essentials (again, full disclosure: I don’t have cable, but I travel extensively [I have a collection of half-used hotel soaps to prove it] so I see them on the road fairly often.) But I see TCM as almost a graduate-school of film with the very top echelon of films. They don’t offer a lot of things that people don’t know anymore.

What were the major studios? What’s a cartoon? What’s a serial? How were they shown? Why did these get made? When did color start? Did silents always have music? These are questions that people ask constantly.

How do I know? I hear these questions all the time. People are interested. I’d love to have a streaming service that housed forums where historians talked about things like this. It’s not out there. It’s going away.

I used to complain that when I worked at classic film houses, they would run all fifties all the time. Then, the boomers got old and stopped coming, and we skipped the 60s and 70s, so it’s all 80s all the time. One place I know shows Ferris Bueller and The Goonies several times a year. They say it’s “hipster-friendly.” But the hipsters don’t know any older films, so why the heck would they come to see them? A lot of them don’t have cable, and so they only see bad quality on YouTube, if they even have knowledge enough to search for it.

I would have started my streaming service a couple of years ago, but I had another problem. I do a lot of tech, but I can’t do it all myself, and I have a tech guy who needs paid. I have a grant writer who is trying to move into other things and won’t return my calls or emails, so basically I have to find another grant writer or be rude and obnoxious to the one I have.

This project is too big for just me; I’d love to have it as a cooperative among film collectors, archives and even studios that will play nice (accent on the play nice.)

But I need $ to get it going, and it’s a chunk too big for Kickstarter. I’d like this to be a public interest 501c3, because, increasingly, I believe that classic film is being culturally neglected and needs a champion out there to make it accessible. I’d like to have a free section and a paid downloads section.

Actually I have a pretty detailed plan for it, if I could just get anyone to care. I’m notoriously bad at marketing (as I’ve pointed out many times), but I really think we’re at a time when culturally we NEED something like this.

Or else it will go away. Like Filmstruck did.

Anyone got any ideas? Let me know. My email is up at top, and the comments will be open for a while, plus you can always start a discussion in the Dr. Film group.

I have a lot of failed, or to put it charitably, incompletely successful projects (if you don’t believe me, I have 400 copies of Little Orphant Annie to sell you), but I don’t want this to be one of them.

What Does “Restored” Mean?

Sometimes ignorance bugs me. I just can’t help it. And I try to let it go, but I can’t do it, because it just builds up and gets worse, so I have to confront it.

Several years ago, I was at the Syracuse Cinefest (now defunct) premiering King of the Kongo, Chapter 5. There were some students in the crowd who came in late and missed my scintillating introduction, and I happened to bump into them on the way out, and I heard their conversation.

“Dude, like I don’t understand what the big deal was on that serial thing. It wasn’t even like restored.”

OK, well, I knew what the big deal was. It was the first time the soundtrack had been heard with the film for something like 80 years, which was cool, and the picture was restored. A lot. But, rather than be a whiner boy, which no one likes, I pursued his reasoning. I asked him what he meant by restored.

“You know, it didn’t look real good. Have you seen the Blu-Ray of Casablanca? They really restored that. This one didn’t look like that. He should have restored it.”

My further contacts with people have cemented the idea that most people have. To be restored, a film has to look like the Blu-Ray of Casablanca. This, apparently, is the gold standard of restoration. Anything less is sub-par.

Further, since digital restoration techniques are magic, this means that if one were willing to put in the time and money on it, all movies that are restored could look like Casablanca, and they all should. It’s simply laziness on the part of restorers who have not put in the required resources to clean up the film.

I heard this again earlier this year with some films I didn’t work on. Universal (bless them) restored several Marx Brothers films, including Cocoanuts, Animal Crackers, and Horsefeathers. Now, Universal had been lagging the field in doing restorations, but their work for the last 5-6 years has been astounding, so I’m a huge supporter of their efforts. But apparently I’m not in good company. I started to see people dogging Universal’s efforts right out of the gate:

“Cocoanuts is not restored. There were always sections of picture that looked bad, and these sections still look bad. They lied when they said they restored it.”

And worse yet:

“How dare Universal claim they restored Horsefeathers! There is a splicy section that’s been there since the 1930s and it’s still choppy! They didn’t restore it at all!”

Wait, what?

So let’s back up. Cocoanuts had several reels where dupe sections were made badly in the 1940s because the negative was rotting, and they had only poor copies. Those reels have not been replaced with better ones, but Universal did what they could to clean up said reels, rebalance the contrast, and match what they could.

Horsefeathers was censored for reissue, and certain things were considered too risque for post-Code audiences. Paramount, who then owned the film, in its wisdom, took the censored footage out of the original negative. In order for this to be found, someone would have to find an original issue 1932 nitrate print of Horsefeathers that is in good enough shape to use. It’s not impossible, but unlikely. Universal cleaned up the footage as best they could, but the missing footage remains. (Let’s give Universal credit and admit that they found a great deal of missing footage from Frankenstein that they diligently restored from discs and alternate prints sources for years. For some time, you could pick up a new issue of Frankenstein, and they’d patch in a scene of Maria getting dumped in the water, or Frankenstein yelling in the lab, or Edward Van Sloan injecting the monster, etc.)

On the other hand, someone did find original nitrate material for Animal Crackers. Apparently the BFI had a near-mint dupe negative of the film that contains about 4 minutes of footage that was also censored for reissue. And, to top that off, it’s about two generations better than what Universal was working with for this title, so the picture is greatly improved. There was nothing but praise for Universal on this one, which was quite deserved.

But why trash them for the other films? They did the best they could.

I know I sometimes sound like the Monty Python 4 Yorkshiremen sketch, but when I first got to be a movie fan, the prints we often had were terrible, and we felt lucky to have them. The studios didn’t care, the foreign archives didn’t care, and the only people who did care were the collectors, who were being raided all the time by the studios and the archives.

I get a little more confused when I consider that every 18 months, it seems like a new restoration of Metropolis takes place. Each time, footage is inserted that hasn’t been seen in years. The last restoration incorporated some footage from a South American 16mm dupe print that looked like a steam roller flattened it, and then sandpaper was run over it for cleaning. No one seems to complain about this, but poor Universal gets the lynch mob called on them for not finding 5-6 minutes of footage. How is this fair?

The idea that I can see Animal Crackers with 4 extra minutes of footage is enchanting to me, but so is the idea that I can see detail in Horsefeathers and Cocoanuts that I’ve never seen before. OK, I’d like to see better material, but it just plain doesn’t exist.

Let’s hit some of the myths here:

MYTH 1: Digital restoration techniques are like magic. If you spend enough time and effort on something it can look like Casablanca.

FACT: This is completely untrue. It’s also putting an unfair burden on Casablanca as the standard-bearer for restoration. The original negative for Casablanca still exists, and backup copies of it, made carefully over the years, are stored around the world. Not to trash the people who did the restoration (which is excellent), but they had a lot more to work with than the Universal did with, say, The Cocoanuts. There was one print of that made as a backup, poorly, in the 40s. That’s it.

Digital techniques are wonderful, but they can’t bring back stuff that isn’t there. When detail is lost in a copying process, it’s gone. I can take dirt marks out, some degree of scratching, splices, and I can rebalance the contrast a little, but if the sharpness is gone, it’s gone.

MYTH 2: The original negatives of just about all the films ever made are stored safely in a salt mine in Kansas or New Jersey, and the studios are just too lazy to go get them.

FACT: There are some salt mines that do have BACKUPS in them, but not original negatives.

I’m working on a restoration of Little Orphant Annie (1918) right now, and it’s going to look worse than King of the Kongo did. With Kongo, we had a 16mm duplicate print, which was copied from a deteriorating and splicy 35mm positive.

With Annie, we have a 16mm Kodascope that’s been censored (they took out some of the scarier scenes), but is more-or-less complete. We have reel one and three of a second Kodascope, which is much darker. We have a 35mm that was about shot when it got scanned, and we have two different reference prints on video from various sources.

And you know what? I assembled a rough cut of all the footage in the film, and I had to use scenes from every one of these prints. Each one had a shot that was different or in the wrong place. I will never, ever get these to match seamlessly. It can’t happen.

On the other hand, you’d get to see some 5 minutes of footage that you’ve never seen before in any other print. Does that mean Little Orphant Annie is restored? Yes, to the best of my ability with the materials that currently exist. If you gave me a million dollar grant to fix it (which I would welcome!), there’s only so much I can do to clean it up.

It will never look as good as Casablanca.

Of Myths and Math

Several people have asked me to expound a bit on digital projection and use math to refute the claims others are making. I have been reluctant do to it because:

a) everyone hates math in blogs and

b) I already think I go on about digital too much.

But that said, I’m going to do what was requested (now several months ago). And now, I’ll get the inevitable hate mail that “you hate digital! You’re a luddite, we hate you, move with the times.” And once again, I point out that I don’t hate digital at all. I don’t like cheap digital that’s passed off as perfection. And the new projectors are cheap digital. We were so enamored of the idea that we could save money that we jumped in head-first before the technology was ready. (I point out, to those newbies, that I did the restoration of King of the Kongo in digital, and then it went out to film.)

Now, I always encourage you to disbelieve me. After all, people call me stupid and wrong all the time, especially on Facebook. (Facebook is the great open pasture where everyone is wrong and no one is convinced about anything.) I carefully referenced everything here, so you can look things up. Even though I may be stupid and wrong, do you really thing all these links are stupid and wrong, too? Well, judging by some political polls, a lot of you do. But I digress.

Let’s hit the biggest myth first:

MYTH: Digital projection is really better than film already (or at least almost as good) and the only people who don’t like it are elitist whiner punks, the same ones who didn’t like CDs over vinyl.

MATH: This is wrong. It’s demonstrably wrong. It’s all about sampling. Let’s take sampling. A digital signal is sampled (http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sampling_(signal_processing) ). The sampling rate of a CD is 44.1kHz (this is 44,100 samples per second). Under the Nyquist sampling theorem ( http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Nyquist–Shannon_sampling_theorem ), this means that the highest frequency that can be reliably heard in a CD would be half of this, about 22000Hz.

The highest human hearing, for an unimpaired individual, measures in at about 20,000Hz.

THIS MEANS THAT IF THERE IS SAMPLING DISTORTION IN A CD, THEN YOU CAN’T HEAR IT. If your dog complains that he doesn’t like the sound of a CD, then you should listen to him. And if he does that, then you must be Dr. Doolittle. (Please, no singing.)

At least this is true for the time-based (temporal) sampling. There are good arguments about the dynamic range causing problems with things like hall ambience etc, but these arguments are often for elitist whiner punks. (I’m kidding, but not a lot… the CD technology is mathematically pretty sound.)

Now for digital imaging, let’s talk the same thing. Let’s not even bother about the limits of human sight, which is what we did in the case of audio. Let’s just make it as good as film. How’s that for fair? Have we ever measured the resolution of film?

Well, sure we have. And I’ll even be extra fair. I’ll go back to the 1980s when we first did this, back when film had lower resolution than it has now. How much nicer can I be?

Back in the 1980s, there was a groundbreaking movie made called Tron. It was the first film that made extensive use of computer graphics. The makers of Tron wanted to make sure that they generated images didn’t show “jaggies,” also known as stair-stepping. This is where you can see the pixels in the output device, which in this case is film ( http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jaggies )

So, they tested their system, and they discovered that they needed to run 4000 lines of resolution before you couldn’t see the jaggies. Don’t believe me? Let’s look at another source:

https://design.osu.edu/carlson/history/tree/magi.html

I’ve actually seen the machine they used to do this. It’s at Blue Sky Studios now. Here is a picture of it:

Now, 4000 lines are needed for a native digital image, or an image that started life as a digitally, not something you are scanning from an outside source. If you’re sampling an analog world, like with a camera or a scanner, you’d need to follow Nyquist’s rule and use 8000 lines. You wanna know why they’re scanning Gone With the Wind at 8K? Now you know.

So you’d expect today’s digital projectors to be about 4000 lines if they’re as good as film, right? Let’s see what the specs are. This is the list for the Digital Cinema Package (DCP), which is the standard for motion picture digital projection.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Digital_Cinema_Package

There are two formats used in DCPs. 2K and 4K. 2000 lines and 4000 lines, right?

DCP 2K = 2048×1080

DCP 4K = 4096×2160

That’s 2048 pixels wide (columns) by 1080 pixels high (lines) and 4096 pixels wide (columns) by 2160 pixels high (lines).

OK, so wait, that means 2048 pixels WIDE by 1080 LINES, right? So the Tron 4K rule says we should be seeing 4000 lines and we’re seeing 1080? Or the 4K top-end projectors, that not many theaters use, they’re using 2160????

So 2K is a big lie. It’s 2K horizontal, not vertical. It’s really 1K.

That’s about half the resolution that they should be running.

Don’t blame me. Blame the math.

Oh, and you know how Quentin Tarantino is always complaining about digital projection being “TV in public?” http://www.digitalspy.com/movies/news/a441960/quentin-tarantino-i-cant-stand-digital-filmmaking-its-tv-in-public.html

Well, what’s HDTV? Well, don’t believe me, see the specs here:

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/1080p

Wikipedia says it’s 1920 X 1080. But wait a second: 2K DCP, used in theaters all over the world, is 2048 X 1080. That’s almost identical to 2K theatrical projection.

Quentin Tarantino is right: Digital film presentation is TV in public, almost literally. Sure the screen is bigger, but that only makes the pixels show up more. (We can argue about a lot of other things Tarantino says, but the math is behind him on this one.)

MYTH: Even though you just showed it isn’t as sharp, it looks better in my theater than the 35mm did, so you’re still wrong.

MATH: The digital projectors look nicer because the 35mm projectors in your old theater were junky, maladjusted, and old. They were run by projectionists and technicians who didn’t care about adjusting things correctly. Sometimes there hadn’t been a technician in the theater in decades. No, that isn’t a joke.

Further, for the last many years, Hollywood has been churning out prints that are made from something called DIs. Digital Intermediates. These are film prints made from digital masters. Almost all of these are made at 2K (1080 lines). Is it any wonder that you project a soft print through an 80-year-old projector with greasy lenses and it doesn’t look as good as a new digital projector showing the same thing? (Digital intermediates started in 2000 or so, the first major film using them being O Brother Where Art Thou? )

Try projecting a REAL 35mm print, made from good materials, especially an old print or a first-rate digital one. Then compare that to digital projection. It’s not even close.

I projected a 35mm print of Samsara a few years ago and I thought there was something wrong with it. Why was it so sharp? It looked like an old Technicolor print. Why was it sharp? Digital imaging at 6K and originated on 65mm film. Worth seeing.

MYTH: There’s nothing to misadjust on digital projectors, so they’re going to be more reliable than the 35mm projectors.

MATH: I know projector repairmen, and they tell me the digital projectors break down more often. I don’t have a lot of measurable math, because it’s early yet, but I’ve seen the sensitive projectors break down very often, and the lamps often turn green before they fail. Since there’s no projectionist in the booth most of the time, then there’s no one to report arc misfires, dirty lenses, etc.

Oh, and the projector is a server on the internet, with a hard drive in it. Computer users will tell you that the internet never crashes, and further, hard drives are 100% reliable. I was working in a theater once where the movie stopped running because someone in Los Angeles accidentally turned off the lamp. (Since the projector was on the internet, some schmo accidentally shut off the wrong projector. Nothing we could do about it.)

Digital projectors can be out of focus, they are sensitive to popcorn oil, they have reflectors that are sensitive and need replaced. Don’t think that digital means reliable.

MYTH: 35mm prints just inherently get beaten up, so they don’t look good even after a few days.

MATH: Dirty projectors and careless projectionists cause most of the print damage you will ever see. Hollywood has had a war on projectionists for about 50 years, and now they’ve killed them off. For the last 35 years, most projectionists have been minimum-wage workers with little-to-no training. They do double-duty on the film and in the snack bar.

These are known in the trade as popcorn monkeys. Please blame them for most print abuse.

MYTH: The credits on digital films look sharper than they do on film, so that means that digital is sharper, no matter what you say.

MATH: Digital imaging favors something called aliasing. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Aliasing. Aliasing means just what you think it might. Due to sampling problems, the signal you end up with is different than the one you started with. It goes under an alias. This gets really technical, but you remember the old days, when they used to have big pixels in video games? (Hipsters, you won’t remember this, but if you’re the typical hipster who doesn’t think anything worth knowing happened before your birth then you won’t be reading this anyway.) Remember this kind of blocky image:

This image is undersampled (meaning that we should have more pixels in it than we do). The blockiness is called temporal aliasing, which means that we are getting a different signal out than we put in! Normally, we should filter this until the blocks go away, because in the math world this is high-frequency information that is bogus and not part of the signal (remember Nyquist?).

This image is undersampled (meaning that we should have more pixels in it than we do). The blockiness is called temporal aliasing, which means that we are getting a different signal out than we put in! Normally, we should filter this until the blocks go away, because in the math world this is high-frequency information that is bogus and not part of the signal (remember Nyquist?).

If we do the recommended filtering, it should look more like this:

This picture more accurately represents the input signal, although it’s blurry, and that’s OK, because the undersampling lost us the high frequency (sharp details) in the image.

This picture more accurately represents the input signal, although it’s blurry, and that’s OK, because the undersampling lost us the high frequency (sharp details) in the image.

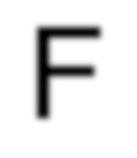

Now, I’ve already shown you that the digital image is undersampled, but let’s take a look at credits. Instead of Lincoln, let’s take a look at an undersampled F:

Now, wait, that looks a lot better than Lincoln, right? If we filter it so we get the actual image we should have been sampling, it should look something like this:

But, wait, I hear you cry: the blocky undersampled Lincoln looked bad, and the blocky undersampled F looks better than the properly filtered F. WHY IS THAT?

That’s because the blockiness of the undersampling just happens to favor the correct look of the F. In other words, we’re getting a distorted signal out, but the distortion gives us a more pleasing image! Credits will look sharper on digital projection, because they don’t do the proper edge filtering. This is why a lot of people complain they can see the pixels in the projection. (You can see the pixels in Lincoln, too, before the filtering.) If you did the proper filtering, you wouldn’t see the pixels, but then the credits would look softer again.

Now, I picked the ideal case with the F, where every part of it was a vertical or horizontal line. The worst case scenario is a S.

An undersampled S of the same scale as the F looks like this:

But with proper filtering, it looks like this:

Your brain filters this out when you’re watching credits and you tend to see the vertical and horizontal edges like in an F, which is what we read for cues with our brain. This is also why filmmakers are now favoring sans-serif fonts, because they render better at low resolution.

Your brain filters this out when you’re watching credits and you tend to see the vertical and horizontal edges like in an F, which is what we read for cues with our brain. This is also why filmmakers are now favoring sans-serif fonts, because they render better at low resolution.

So the credits aren’t sharper. It’s an illusion caused by undersampling and your brain. And I showed you with a minimum of math. YAY!

Fun with signal processing!!!

MYTH: OK, Mr. Boring Math guy, I still think that the digital stuff looks better. Can you show me a combination of what you see in digital projection vs. what it should look like?

MATH: Why yes! Thank you for asking!!!

What I notice most about digital projection is that they have boosted the apparent sharpness with something called a Hough transform, which make edges look more pronounced. This also causes edging artifacts (called ringing) that I find obnoxious.

Further, the green response is compromised rather a lot. Most digital projection I see today represents all grass as an annoying neon green. It can’t seem to represent a range of colors. We’re also getting an overly red look to compensate for the strange greens. Let’s take an ideal case: this is a Kodak color sample:

Now, I’ve exaggerated this to make it more obvious for you, but here’s what I see in most digital projection:

Notice we’re seeing almost no green in the avocado, the grapes look dead, the flesh tones are too red, the whites are AAAAALMOST blown out, and we’re seeing edge artifacts from over-sharpening.

This, folks, is why I miss film. We could do digital and do it well, but we’re not.

And, you ask, why is it that we just don’t use more pixels, use better color projection, so we don’t have to do this? It’s because more pixels = more hard drive space = bigger computer needed = more cost. Since Hollywood is in love with cheap, they’re not going to do it right until right is cheap.

Janitor in a Booth

I’m not much of a social butterfly and I have no innate “sense” of how these things work. I do know one odd thing: if you’re a projectionist, then you’re considered the lowest of low in society. I’m not sure why this is. It may be the plethora of underpaid teenagers who were relegated to projection booths, most of whom screwed up prints and caused the presentations to look bad. I suspect that it’s something deep-seated in the heart of a lot of arts organizations, and I’ll write more about that in a bit.

As most of you know, I make a “living” doing film presentations and preservations, and I prefer the look of projected film. I’ve worked in scores of venues, from Lincoln Center to a dilapidated opera house in Delphi Indiana that rained plaster from a leaky ceiling. Some places have their own projectors and a staff projectionist, but often, if I’m going to run film, then I need to bring my own projectors.

In order to make ends meet, I also act as a projectionist-for-hire, which is one of the jobs I hate most. That’s when I get treated the worst. I’ve had amateur filmmakers yell at me for running their film with not enough “pink” in it, and I had another guy who had me change the volume on his movie 200 times. (That’s neither a typo nor an exaggeration.) Sadly, a lot of people shoot things on their phone and then, when it looks different on a 30-foot screen, they panic.

And then the worst one: I was working at a museum once who had Peter Bogdanovich come in to introduce Touch of Evil. That’s great, because he’s an expert on Orson Welles… in fact Welles lived in his house for a while. But Bogdanovich is also a director who’s made some cool pictures, and I’m a big fan. I spliced together a best-of trailer reel of several of my favorites, and I also got the reissue trailer for Touch of Evil touting all the restoration techniques that went into it. It was all 35mm and all ready to get to the projector.

But they wouldn’t let me run it. And I was never allowed even to speak with Bogdanovich. I could look over and see him, and I wanted to ask him about Noises Off and The Cat’s Meow. He had interviewed heroes of mine like director Allan Dwan. Couldn’t ask him anything about it. Whatever for? Were they afraid I was going to give him projectionist cooties? Sprocketosis? What’s the deal?

My guess is that this is something of an arts caste system. Put simply, I think there’s this idea of there’s them what does the art, and there’s them what supports the artist. These “non-artists” are somehow less valuable people than the “artists.” And they shouldn’t mix company. That would be bad. Apparently, you don’t want to besmirch yourself with contacting someone who is in the support mode. That includes the sound guy, the janitor, the security people, and the projectionist. They’re like the untouchables in the caste system. Neither to be seen nor heard.

Now, the problem is that I’ve got my feet in both worlds. I have to. If I have the only print of a film, then you know who’s going to project it? I AM. I’ll insist. The fact that I’m a historian/collector makes me an artist, but the projectionist is support only, and contaminated.

So the arts communities, particularly my local one, don’t know what to do with me. I’m not the only one who encounters this. Just last night, a friend of mine from Boston, who knows more film history than most professors, was told, “You know, most projectionists don’t get to pick films like you do.”

What? So this guy has been demoted from a valuable commodity to the being the equivalent of a janitor in the projection booth. (Not that I’m trashing janitors, mind you… they provide a tremendously valuable service.)

Oh, and it’s not isolated. There’s been a huge stink in LA about underpaid projectionists, which is odd, given that there are fewer and fewer of them anyway. You’d think that the ones left working are the good ones that are really needed.

I seem to get more film historian jobs outside my local area, and I find that I seem to get more respect (and hence pay) the farther I am from home. This is why I love to hang out at film conventions where they run oddball films (sometimes mine). It’s great to be around folks who understand film and respect it as an art form, but I still struggle with carrying that idea back to my local area, where I’m apparently contaminated with projectionist ptomaine.

And that’s really sad, because it means that, instead of consulting me, programs are created by “arts people” who are completely and utterly ignorant of film. And it means that everyone programs the same five films all the time. I know of three different showings of Wizard of Oz in my area just this year, and it’s only February. OK, it’s a great film, but haven’t they made anything else? Oh, yeah, I guess Casablanca.

Again, I don’t quite understand this, but I’ve responded to it. I have taken to avoiding projection-only jobs. I don’t ever promote myself as a projectionist. I promote myself as a film historian/collector/presenter.

This has even affected my choice in vehicles. A while back, my dad was noticing that I was constantly loading film and equipment in and out of my car. He said that I should buy a van, so I could leave stuff in there all the time. I told him that I couldn’t, and I told him why.

“Dad,” I said. “It’s a perception thing. The projectionist owns a van. The film historian has a car. I have to have a car.”

“Oh,” Dad said, thinking a bit. “I understand.”

I’m still not sure that I do.

Kongo Lessons

Restoration Demo for King of the Kongo (it looks even cooler in HD!)

Some of you may not be aware that I’m in the midst of restoring The King of the Kongo (1929), which is the first sound serial ever made. You’d think that people would be happy that I’m doing it, but I get frequent complaints about it, and a lot of questions. I’m going to answer some of these today.

Q1: Why are you restoring a serial that’s bad and the prints aren’t great?

A: Because it’s bad and the prints aren’t great. The archives weren’t interested in this one. I tried. They didn’t care. They probably shouldn’t care, either, because part of their job is triage. I think it’s important—it is important—it’s just that there are a lot of films in worse shape that are in line ahead of it, so I’m doing this myself.

The bottom line is that I knew that if I didn’t restore it, then no one would, and I knew where all the elements were, so I wanted to get it done while we could.

Q2: Is the whole serial sound?

A: The serial is part silent and part talkie. The trade papers are a little confused about this, so I can’t prove this theory. The trades at the time announced The King of the Kongo as being available in silent and sound versions. There’s even an announcement that the silent version is finished and they’re starting on the talkie version. But there’s no mention that I can find anywhere of the serial being played without sound. I suspect that there was only a sound version released, and that is part silent (with synchronized music and effects) with one scene per reel with synchronized dialogue.

Q3: What survives on the serial? Are you restoring the whole thing?

A: The entire picture exists. There were 21 reels initially and we have 10 reels of the sound. That’s a little less than half of the original sound that survives. Of those, Chapters 5, 6 and 10 exist with complete sound. Three other chapters have one reel of sound with the other still being lost (each chapter is two reels and hence two discs of sound.)

I restored Chapter 5 with Kickstarter funds, Chapter 10 with National Film Preservation Foundation funding, and Chapter 6 is being done now. For all three Chapters, I owe thanks and funding support to Silent Cinema Presentations, Inc. (There’s a lot of drama about how Silent Cinema saved my bacon in previous blog installments.) I may go back and restore the the picture for the rest of the episodes and drop in the sound for those parts that survive. The complete chapters that survive have been archived to film.

Q4: This is the digital age. Why waste money on film?

A: The restorations were done digitally and archived on film because film never crashes and goes beep when you turn it on. Film is archival.

Q5: Are you going to put this on YouTube?

A: No.

Q6: Will it be available on Blu-Ray?

A: I hope so.

Q7: A friend of mine told me that UCLA has 35mm prints of this serial and so you’re wasting your time on this bad print you’re restoring.

A: I hear this rumor all the time. You know what I did about it? I contacted UCLA. You know what they told me? They have a 16mm print, just like mine and it’s under a donor restriction, so I couldn’t access it anyway. There is one more print in the US that I’ve heard about in private hands, and I couldn’t access that. There’s another 16mm print in France that’s not better than mine. There’s a partial 35mm in an unnamed US archive that’s also under donor restriction, meaning we can’t get to it. So that’s it, folks. I contacted the donors for permission and they said no.

You want footwork to find the best materials? I did it.

Q8: It’s frustrating to watch a serial a chapter at a time and then out of sequence. Why don’t you wait until you find all the sound and restore it then?

A: Because we may never find all of the sound. And right now, we’re at a point where I can sync the sound and picture with the help of some people I know. Later on that might not happen.

Q9: Why did you restore Chapter 10 and then Chapter 6?

A: Because we found the complete sound for Chapter 6 after Chapter 10 was already underway.

Q10: There’s a whole group of people who do serial restorations who are spreading bad rumors about you. Do you hate them?

A: No. I can’t hate people who do restorations. I contacted those people some time ago, offered to pool resources, and was told to go away. So I went away. They were convinced that they could do a better restoration than I could do, and that they knew where all the sound discs were. To date, they have not done a restoration. I would still be happy to pool resources with them. I feel that films should be restored from the best elements. If they know where better materials are (and they might exist in private hands), then I’m willing to help. I suspect that the elements they thought were complete were the same incomplete ones that I found in private hands, and I bought them so I could do my restoration. But I would still help them if they asked.

Q11: I heard that Library of Congress has all the sound discs.

A: I heard that too. I asked them, and I contacted the film people and the audio people. Do you know what they told me? They don’t have them.

Q12: Does this look better than the DVD that I bought of this?

A: You bet it does.

Q13: The DVD I bought is silent with music, but has long stretches with no titles. Is your music the same?

A: You have the sound version missing the dialogue track. About half of each episode was silent with intertitles. The remaining half had dialogue. The music on your DVD is patched in later to go with the action. The original score by Lee Zahler is on the discs, plus dialogue in all those long stretches with no titles.

Q14: I heard a rumor that you may start a Kickstarter program to release a Blu-Ray. That seems kind of crooked to me, since you got grant money to do the restorations.

A: I got grant money to do the lab work for the restorations. The lab work (scanning, track re-recording, and digital film out) was covered. All the by-hand work (sync, image restoration, etc.) was free. And we’d need to do that work on the 7 chapters that still need their picture restored.

Q15: Did you learn anything of historical significance while you were restoring the serial?

Yes, some.

Ben Model’s undercranking theories are borne out here. The silent sequences are shot at about 21-22 fps and then played back at 24. The actors haven’t adjusted to this yet, so they’re still playing slower for 21-22 which makes the dialogue deadly slow. Once again, we see that audiences in the silent days were used to seeing films played back slightly faster than they were shot.

This film has some very interesting set design and some interesting lighting, almost expressionistic. It’s mostly lost in the prints we see today.

Despite the fact that the film has that deadly 1929 slow pacing, I note that director Richard Thorpe has put some interesting touches in it. There’s a long shot in which Robert Frazier is tailed by Lafe McKee and William Burt. It’s staged to show off the set and so that we get a sense of distance between McKee and Frazier, but it’s all done in one shot with no cutting. There’s not a second where nothing is happening onscreen, but it’s done very economically.

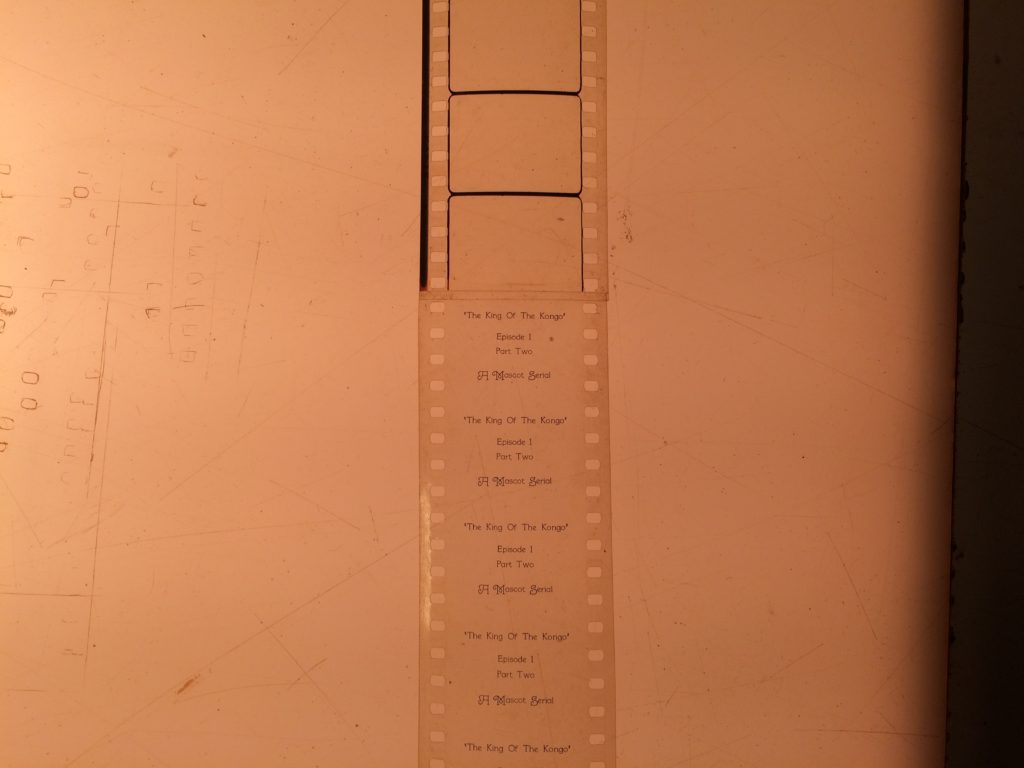

Mascot used black slugs (pieces of leader) to resynchronize shots that had drifted out of sync. I’ve seen this in The Devil Horse (1931), The Whispering Shadow (1933) and The Phantom Empire (1935). I could have taken them out, but it’s part of the Mascot “feel” and “history,” so I left them in. There are several in Chapter 10.

There’s a little throwaway line in which Lafe McKee refers to Robert Frazier as “black boy.” It’s 1929 racism. I left it in (you probably wouldn’t have noticed if I’d cut it.)

Q16: You were talking about donor restrictions. Do you mean that the donor of the film restricted access to the films after donating them?

That’s exactly what I mean.

Q17: You mean that we spend taxpayer money housing and cooling films that the donors won’t let us see?

I do mean that, yes. And that’s the topic of another blog post. Remember, I don’t make the rules. I just live with them.