I’m the guest blogger on the Indianapolis Museum of Art’s site today. Interesting reading, I hope, from a film restoration standpoint, even if you’re not attending the screening:

Month: January 2012

An Artist is Born Singin’ in the Rain

I’ve been bombarded with questions about The Artist. Everyone I see asks me about it. I felt that I had to give it a look, and a fair chance, before answering.

I’ve been bombarded with questions about The Artist. Everyone I see asks me about it. I felt that I had to give it a look, and a fair chance, before answering.

Before I go on too far, let me say that I’ve seen zillions of silent films. I know how they are supposed to look and feel. I am a harsh judge of movies that get history dreadfully wrong and don’t seem to care about it. I have been a vocal critic of Singin’ in the Rain (1952) for many years. Sure, it has great singing and dancing in it, but it gets the feel of the era entirely wrong, and it puts “history” out there that is completely and utterly bogus. I wince every time I see the movie.

I went to see Hugo a while back, in a nice theater, in 3D, and it underwhelmed me. This ties in with The Artist, because Hugo is another film that is set in that same period, the late 1920s and early 1930s. Hugo did a delightful job recreating the period. Ben Kingsley is brilliant. The effects are great. Most of the history is fairly good, although it’s been warped for ease of storytelling. Ultimately, for me, it didn’t say enough about the magic of movies and had a tedious, predictable sub-plot with the station inspector. The sub-plot felt like it had been ripped from the film adaptation of Chitty Chitty Bang Bang, and we all had to wait for this plot element’s resolution before getting back to the main action. Mostly enjoyable, but not a film I’d call a classic.

Many films that are set in this period get the history so far wrong that I want to throw things at the screen. I generally don’t have to do this, because some moron in the front row is already doing it by the time I find my motivation level rising. Public Enemies, the Johnny Depp film from a couple of years ago, was particularly offensive. The filmmaking techniques were right out of Michael Bay: cut-cut-cut editing, mushy shot-on-video camerawork, never a tripod or steady shot. Depp’s Dillinger robs palatial block-wide banks in rural Indiana–located in towns that are still just barely dots on the map. Not only does it get the facts wrong, but it gets the feel wrong. Public Enemies plays like teenager’s first feature-length video on YouTube. We might have been impressed that a teen could pull off such a feat, but we’re embarrassed that talented professionals would allow their names to be attached to such a lousy film.

I’m inclined to give a movie a break if it tends to get the feel right. Some are better than others. The Sting is so accurate that it sometimes feels colorized. O Brother, Where Art Thou? plays fast and loose with the facts, but when it gets down to brass tacks, the film feels authentically 1930s. I recommend both movies. I hesitantly recommend Hugo, too, although with some reservations.

And on to The Artist. This film has pretensions you can cut with a butcher knife. Not only does it attempt to recreate the 1920s/30s, but it is also presented in black and white, in the 1930s aspect ratio, and, most importantly, as a silent film. It’s tough to make a silent film these days. First, modern audiences aren’t used to the dramatic techniques used in them, so sometimes they’ll draw an unintentional laugh. Second, a lot of things have changed in the intervening years, so it becomes a technical challenge.

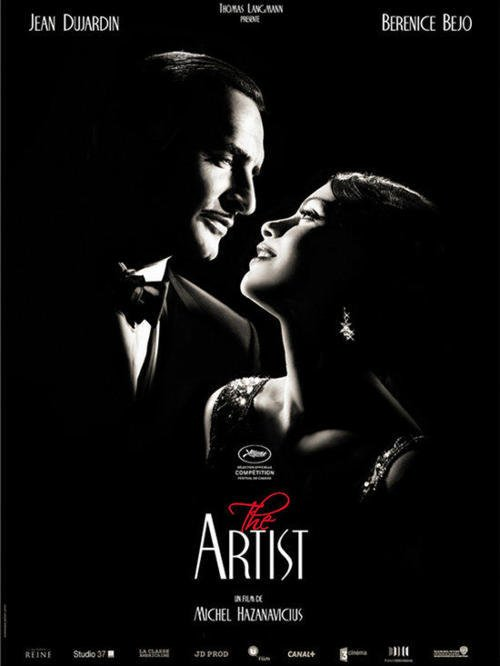

Does it work? Yes, it mostly does. The plot is fairly pedestrian, basically a retooling of A Star is Born, but that plot was old in 1937. George Valentin, a major silent star, played by Jean Dujardin, is a little careless in his personal life, has an alienated wife, and meets Peppy Miller, a rising young flapper, played by Bérénice Bejo. As sound comes in, he is increasingly unable to maintain his status, while Peppy goes on to major success.

The film progresses and we see Valentin’s downfall as we see Peppy rise to greater and greater heights, up until, well, you oughta see the movie.

Dujardin turns in an excellent performance. He manages to capture the swagger of Douglas Fairbanks with a bit of the continental charm of Ricardo Cortez. It works well within the context of the film. Bejo is not quite as good, although still commendable. She just seems a bit too bubbly at times. Also at hand are reliables like James Cromwell as the long-suffering chauffeur/butler, and John Goodman as the studio chief. They are nothing short of great, but then I would expect nothing else from them.

Director Michel Hazanavicius does a great job recreating the style of the times. Not too many closeups, which we love to use today, slower editing pace, and he even undercranks the film just a hair to give it that late 20s feel. It works. He matches the style of intertitles and even recreates the 1920s fonts very well. (You knew I was picky.)

I just wish it had been more, somehow. I suppose that it should be enough that Hazanavicius has recreated the period well enough that he’s made a run-of-the-mill late silent picture. If you’re hoping for a truly great silent picture, a drama like Sunrise, a love story like Lonesome, then, well, it isn’t here. This isn’t necessarily bad, but I can tell you that I’ve been to conventions to watch day-long silent film marathons, and The Artist would not be a huge standout. It would get good reviews, a few smiles, and we’d move on.

There are myriad little nitpicks, from the unblimped Mitchell cameras to the 2000’ film cans, to the way the nitrate doesn’t burn fast enough, to… well, OK, you get the point. More severe are problems later in the picture. Peppy Miller seems to be in 1920s flapper attire, short skirts and all, way too far into the 1930s. The climactic sequence uses a music style that almost sounds like big band music from the early 1940s, which isn’t right, either. The cutting is actually too slow, and there is a tendency to dwell on to actors speaking without cutting to an intertitle, which would not have been done at the time. But I nitpick.

The single greatest failure of the film, to my mind, is a plot point. Goodman’s studio boss calls Dujardin into his office and basically fires him, saying that the movies need to flush out all the old silent actors and replace them all with new ones.

WHAT?

Sure, there were silent actors who didn’t make it far into the sound era. A lot of leading ladies got older, were married and retired. Lon Chaney died. John Gilbert was an alcoholic and was probably blackballed by Louis Mayer. Douglas Fairbanks found sound films dull to make. Chaplin took time to adapt to sound. But there were so many others who starred both in silent and sound films, many who didn’t even seem to notice the bump…

Laurel and Hardy, Charley Chase, WC Fields, Ronald Colman, Ricardo Cortez, Gary Cooper, Warner Oland, Greta Garbo, Norma Shearer, Joan Crawford, and Loretta Young all sailed through the transition. Even though comedy didn’t flourish in the 1930s as it did in the 1920s, still stars like Buster Keaton, Harry Langdon, Vernon Dent, and many others, at least found work. Harold Lloyd was especially prosperous in the sound era. Keaton’s downfall came not with the advent of sound, but rather with his contract moving to MGM, and even with his boozing and bad films, he still worked steadily through the 1930s.

The idea that stars were summarily flushed out of the system for talkie stars is just wrong. There were a few stars with unsuitable voices, which is an idea that was blown way out of proportion with Singin’ in the Rain. Raymond Griffith had a vocal injury and couldn’t speak above a whisper. Sound films didn’t quite end his career, but it was close. Karl Dane had a very thick accent and had trouble in sound films, as did Anny Ondra, whose voice was dubbed in Blackmail (1929). In general, even those actors with relatively thick accents still did well: Bela Lugosi, Charles Boyer, and Paul Lukas come to mind quickly.

This is why the biggest flaw in The Artist is the goofy idea that a studio would summarily drop a big, moneymaking star who simply had yet to make a talking film. I can’t think of a single time that happened. Perhaps someone can correct my memory. Movies are, and always have been, about making money, not about art. If the star makes money for them, they’ll put up with about anything. As soon as they stop making money, they’re out. Do you honestly think that studios would have put up with the drug-addicted, temperamental Judy Garland had she not been brilliant and profitable?

No one should ever get their history from movies made about movies. For some reason, films are neglected art and film history seems particularly unimportant. I have no idea why, but you’re more likely to get a good reconstruction of a Napoleonic campaign than a talking film from 1931.

***Special Side Note***

Kim Novak has gone on record complaining bitterly about the use of music from Vertigo (1958) during the climactic section of The Artist. Her remarks were pointed and used a rape metaphor. Novak has been accused of looking to get her name in the papers again, and of being overly sensitive. The music is used to back up a particularly poignant scene, and no one ever did poignant like Bernard Herrmann, the composer of Vertigo’s score. Several people have said that it doesn’t really matter, because the music is from an old film anyway, and, after all, who would notice?

Here are my two cents’ worth: Who would notice? Gee whiz, guys, you are making a movie and targeting fans of older films. Don’t you think it would be obvious? Vertigo isn’t just some old movie… it’s an all-time classic, and it’s one of the greatest film scores ever written. People know it. A lot of people know it. Don’t believe me—believe Google. Perhaps Ms. Novak is a little extreme in her wording, but she has a good point. If I were writing a symphony, I could easily lift the last few minutes from a Beethoven symphony. It might work well, and it would be perfectly legal. But why would I do that?

Artistically, it’s a bad call. It immediately took me out of the film. The rest of the score, by Ludovic Bource, is quite excellent at imitating the style of the period. He even does a pretty good job of foreshadowing the quote from Vertigo. But it still doesn’t match. Vertigo is 1950s Herrmann, not 1920s pop. It’s great, it mostly works, but it’s intrusive. I would have been happier with an ending by Bource. I think he could have done it justice. (For an illuminating answer as to why Bource didn’t have his music in this scene, please check Bruce Calvert’s comment below. I didn’t know about it before publishing this.)

I am not going to jump on the bandwagon criticizing Novak. She is not stupid, and she is not a publicity hound. The use of Vertigo music in The Artist is strictly legal and above board, but I don’t think it works with the film. Vertigo is Vertigo and I think it would have better been left alone.

All that said, The Artist is still a fun film, and a great cinematic experiment.