Find out more on the Film Preservation Blogathon here. Donate here. The host blogs are Marilyn Ferdinand’s and Rod Heath’s.

Find out more on the Film Preservation Blogathon here. Donate here. The host blogs are Marilyn Ferdinand’s and Rod Heath’s.

I read about this blogathon with some interest. They’re raising funds for preserving and distributing The White Shadow (1923). This is a worthy project, since it’s one of those films that won’t be preserved by normal methods. We only have the first half of this film that Alfred Hitchcock co-directed. It isn’t really a Hitchcock film, and it isn’t complete, and Hitchcock remembered it as not being very good.

Exactly the kind of thing I’d love to see! Why? Because it will show just how Hitchcock developed as a director, and I love the work of some of the actors (especially Clive Brook) in the picture.

And since it’s not really terribly historically important, and incomplete, it will get shoved on everyone’s back burner. Again, that makes it the film I want to see.

I’ve been reading over the blogs on the blogathon so far, and there are quite a lot of them about Hitchcock and Hitchcock-related films. It got me thinking how I could contribute in my generally contrarian way, not really talking too much about Hitchcock, which I think is being covered adequately by others.

What isn’t being adequately covered is the thing that is most dear to my heart, which is film preservation itself. I got myself to thinking what other projects I’d love to see preserved. Now, many of you loyal readers (I realize this is an impossibility since I have too few readers to be called many!) will cry foul. Since I am involved in film preservation myself, I’ll naturally pick projects that I’m already involved in.

Well of course! That’s why it’s my blog. If you’d like to rant about your own special projects, then write about them in your blog.

Here, then are some of my top picks, in no particular order. I have restricted these to films that actually exist and could be preserved or restored, but nothing is currently being done.

- Thunder (1929). This is Lon Chaney’s penultimate film, for which about 12-16 minutes exist. I know that it was a big deal a few years back when Rick Schmidlin did a stills-only restoration of London After Midnight. Well, Thunder has two advantages over that film: a) There is actually some footage that survives and b) all indications are that it was actually a good picture. The disadvantage that Thunder has is that it’s not a lost Tod Browning picture, and few people have heard of it. I’ve been told by archivists that the photography on this film is as lovely as any ever shot, and this comes from jaded guys who have seen everything. I’d love someone to care about this film in the same way people cared about London After Midnight. Even half as much. Chaney is always an amazing actor. His work should be seen.

- Seven Chances color restoration. What?, I hear you ask. Didn’t you already do this? Yes, I did. I even wrote about it a zillion times. What I hope I proved was that a full-scale restoration could be done in the right way, from good-quality film elements, combining the best of multiple print sources. There are a number of people who would need to collaborate on this project, and it would be expensive to do it right. I hope the politics can be overcome and this film can be preserved in the way it deserves. I think my restoration could be vastly improved if we just had better source elements.

- Little Orphant Annie (1918). Not only is this a rare early Colleen Moore film, but it’s also one of the only appearances ever made by poet James Whitcomb Riley, in a film that was probably made at his house by Chicago filmmakers. I don’t know for certain, because I haven’t seen it. Film historian Bruce Lawton located a nitrate print several years ago, and I tried to raise funds to restore it from local historical societies and the Riley Foundation itself. They didn’t have the money. The print has subsequently been donated to an archive that has no immediate preservation plans. Complicating the issue is that a truncated version was duplicated (rather poorly) by a dubious collector in the 1970s. It’s felt that this version may be “good enough” even though we may have a complete original nitrate, which would be longer and better. The last I heard was that the nitrate was starting to get sticky. I hope that people wake up before this film is gone.

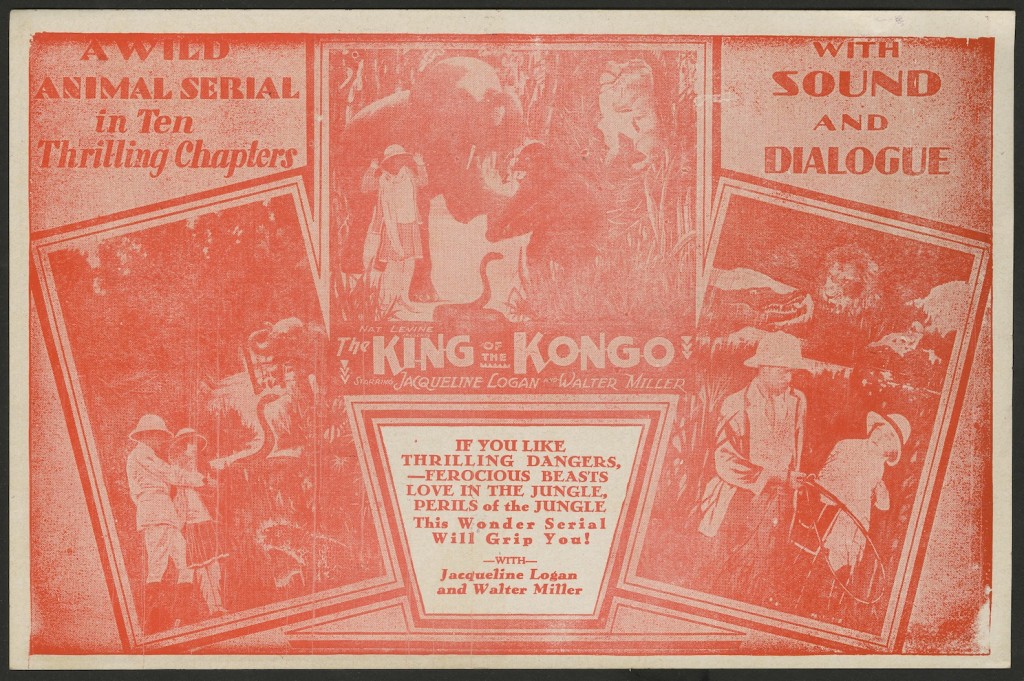

- King of the Kongo (1929). Hey, wait! Isn’t this a pet project? It sure is. I wrote about it here. Vitaphone researcher Ron Hutchinson located the original sound discs for three reels of this rare serial and they do sync with my silent 16mm print. I was able to restore the sound to the reels for the first time in 80 years. The pluses? It’s the first sound serial, and an early Boris Karloff film. The minuses? It’s painfully acted by people desperate to dive in for the immobile microphones, and it isn’t very good. We only have the sound for one complete chapter. The agonizing part: another collector has several more discs and smells money, so he will not lend these discs for a restoration, but will only sell them for an outrageous sum. Even with all the extant discs, we’d have less than half of the serial restored to sound, and I’ve got to tell you that the blu-ray sales of this one would be in the single digits. Still, it’s cool and it should be restored. I’m probably going to do a Kickstarter project to get it done…at least what we have now.

- Beggar on Horseback (1925). Gee, a silent picture directed by James Cruze, with Edward Everett Horton, from a play co-written by George S. Kaufman. Could this be a hidden gem? You bet it is. The good news is that it has been preserved, but the bad news is that it’s missing the last reel. I’ve seen it; it’s wonderful, bizarre stuff. I’d love to see this released on some sort of video with stills and bridging text. It’s not been done yet, but it should be. The trouble? As usual… copyright issues from a studio that thinks no one cares. I hope they’re wrong.

- Showdown at Ulcer Gulch (1958). OK, this one isn’t very good. I admit it. The “review” on IMDb by the fraudulent F. Gwynplaine MacIntyre makes it sound worse than it is. Chico Marx’ son-in-law, animator Shamus Culhane, directed this piece for the Saturday Evening Post. It’s no more than 15 minutes or so, but it contains cameos by no less than Groucho Marx, Chico Marx, Edie Adams, Ernie Kovacs, Bob Hope, and Bing Crosby. It stars Orson Bean and Salome Jens. I found a faded Eastman color print of this in 2001, and it is in desperate need of a color restoration. The color negative may still exist, but it’s on very unstable stock (1958-62 Eastman negative is particularly bad at fading), and it may be too far gone. Historically important? You bet! I’m not sure what the problem is, but someone is claiming a copyright on it. I’ve offered it as an extra to two separate boxed sets and have been turned down twice.

The Haunted (1965). Yes, this is another of my own pet projects. After many years of searching, I found a print of this on eBay a couple of years ago. I’ve written about it before, but it’s a wonderfully spooky pilot by Joseph Stefano, co-creator of The Outer Limits and the screenwriter for Psycho (1960). Hey, I got in a Hitchcock reference! There are more here: Hitchcock stars Martin Landau (North by Northwest), Diane Baker (Marnie), and Dame Judith Anderson (Rebecca) are the top-billed actors. Spooky photography by Conrad Hall, and a beautiful, lyrical script by Stefano make this an unheralded classic. 16mm material exists in the hands of at least one archive and a couple of different collectors. 35mm material exists in the hands of a major network. There are two different cuts, both a pilot at 60 minutes and a feature cut (distributed to Europe) at about 90 minutes, but it’s languishing in contract problems. Is there a negative? Do we need a restoration from the surviving prints? It’s not clear. I can’t recommend this highly enough: it’s as good as the best of the Outer Limits episodes, yet no one can see it. Maddening.

The Haunted (1965). Yes, this is another of my own pet projects. After many years of searching, I found a print of this on eBay a couple of years ago. I’ve written about it before, but it’s a wonderfully spooky pilot by Joseph Stefano, co-creator of The Outer Limits and the screenwriter for Psycho (1960). Hey, I got in a Hitchcock reference! There are more here: Hitchcock stars Martin Landau (North by Northwest), Diane Baker (Marnie), and Dame Judith Anderson (Rebecca) are the top-billed actors. Spooky photography by Conrad Hall, and a beautiful, lyrical script by Stefano make this an unheralded classic. 16mm material exists in the hands of at least one archive and a couple of different collectors. 35mm material exists in the hands of a major network. There are two different cuts, both a pilot at 60 minutes and a feature cut (distributed to Europe) at about 90 minutes, but it’s languishing in contract problems. Is there a negative? Do we need a restoration from the surviving prints? It’s not clear. I can’t recommend this highly enough: it’s as good as the best of the Outer Limits episodes, yet no one can see it. Maddening.- Mack Sennett credits. Paramount sold its library of short films to NTA in the 50s. NTA retitled them for TV issue. In many cases, this was butchery of the highest order, but it was done for legal reasons. In some cases, original negatives, uncut, survive, but in others, we are not so lucky. Mack Sennett did a series of shorts for Paramount in the 1930s that had a unique opening: a bulldog came out of a dog house, barking twice, and then a fade into the main title (a spoof of the popular MGM lion opening). In most cases, NTA just froze the main title, leaving the soundtrack alone, so it’s possible to hear the dog even though we never see it. Fortunately, there are a few surviving prints of the barking dog visuals. I’d love to see these restored to the Sennett shorts, because they give a fresher, more vibrant open to these films. I’ve worked on it a bit, and I think it could be done with more of them…

- Hard Luck (1921) This is one of the maddening problems in film when a movie is really too profitable, so people fight over it. An early Buster Keaton short, it does not exist in complete form. However, there are two different versions, each with different footage, that survive, and since Keaton makes money, both versions are available on video. I hate it when this sort of thing happens. I fully sympathize with the problem, because I know that Keaton pays the bills on other projects that are worthy but pay less. In this case, I really wish the two players could get together and cooperate so we could get a more complete version of this short.

- The Lost World (1925) Long a holy grail of film restoration, it was a big deal when a extra footage from this film finally resurfaced in the 1990s. Historically, it’s a knockout, because it’s the first ever giant monster film with dinosaurs found in a “lost world,” a set piece so powerful it was even stolen for the movie Up (2009). A major archive did a complete restoration of The Lost World from the best materials, and they did some roadshows around the country. Alas, they wouldn’t release it on video. This meant that another company did another restoration on it and released it themselves. The result? You guessed it. The two prints each have footage not in the other, meaning that no one yet has seen the complete version. I’d love to see the various political factions work out the problems here so that this film can finally get the restoration it deserves.

- The Mascot (1934) This is an early sound stop-motion short, with lovely, almost stream-of-consciousness animation. A couple of years ago, the Library of Congress reprinted a beautiful 35mm of this relatively common short that contained a great deal of material I’d never seen before! Ironically, my own print contained footage not in theirs! This short has been cut and recut so much over the years that the original intent of Starevitch’s wonderful work is often blunted or lost. I have a feeling that it would make a bit more sense if we had more of it to tie the narrative together.

- The Treasurer’s Report (1928) Robert Benchley’s groundbreaking and hilarious monologue was one of the first sound-on-film releases from Fox. Long available in hideous dupes, with the most common print marred with an ugly defect that looks like a tarantula leg stuck in the optical printer, this film appeared to be doomed to a life of substandard picture and hissy image. I found an original diacetate 35mm print in the hands of a collector several years ago, and another collector owns a beautiful 16mm reduction print from the original negative. Between the two prints, an almost pristine restoration could be made. Will it happen? I doubt it. The copyright on it is dubious, and there’s a problem deciding who owns what. It deserves to be saved.

- Freckles (1935) Ostensibly based on the book by Gene Stratton-Porter, this film ends up being a completely separate work. It’s also basically a lost film starring Virginia Weidler and Tom Brown. I found a badly vinegared print, still runnable, on eBay a few years ago. As far as we know, it’s the only surviving print. There’s the usual trouble: it has a copyright renewal, but no one knows who owns it now. As a result, I can’t show it except in archival conditions, I can’t copy it to video without contravening the Digital Millennium Copyright Act, and three archives have turned me down on my offer to have it preserved. One offered to store it for me but not to do any work on restoring or preserving it. No thank you!

No, there’s no Greed here, no London After Midnight, nothing really earth-shattering. There is a great deal of material that’s interesting and historically important. Some of it may be preserved eventually, some may see the light of day, but I expect some to continue languishing.

That doesn’t mean I’m not in there fighting!

I love the idea of a blogathon that actually results in a film being preserved. I have always been told that no one cares about old films, particularly silent ones. Please, just for me, prove those people wrong!