I’m posting this in various groups that are asking me about this. If you follow me on the Dr. Film page, you may have heard some of this, but it’s worth reading because there’s new information in here too.

THE PROJECT:

King of the Kongo is the first sound serial, made in 1929. Although it’s been on video for years, the prints available are really bad, and they were all made from the sound version without the sound discs, so not only does it look bad, but doesn’t make sense without the sound.

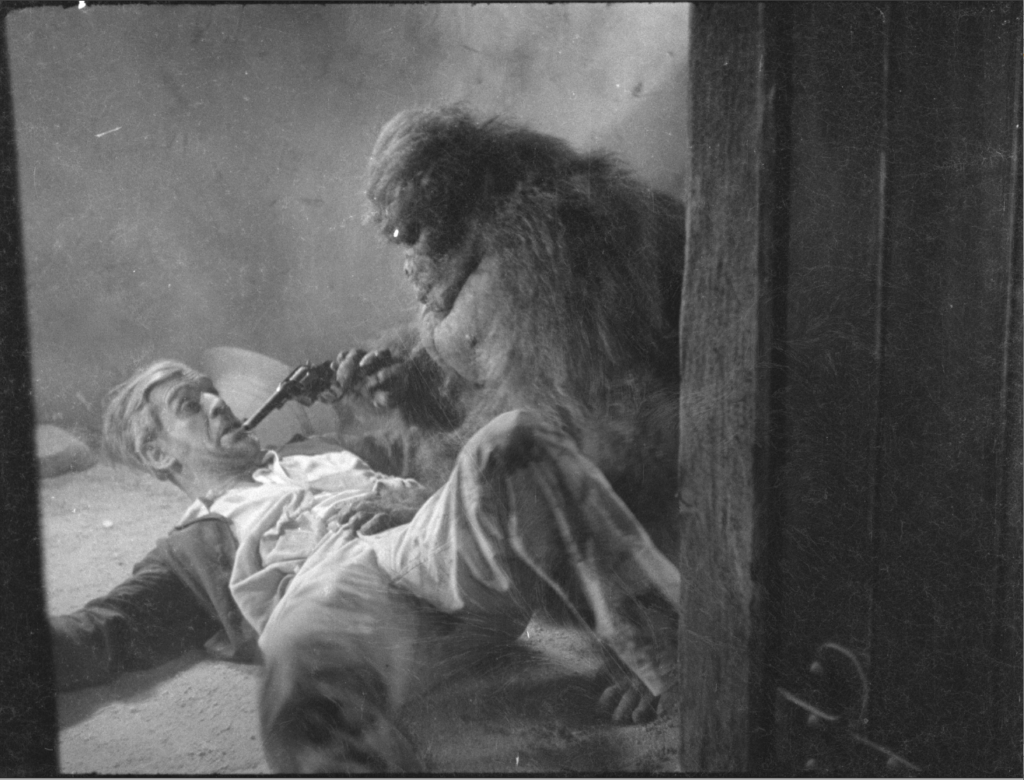

It’s not a great film, but it’s fun. I think it was partly the inspiration for Son of Kong, which also takes place in a wrecked temple, has a gorilla, jewels, and some dinosaurs in it. Other than that, they’re different!

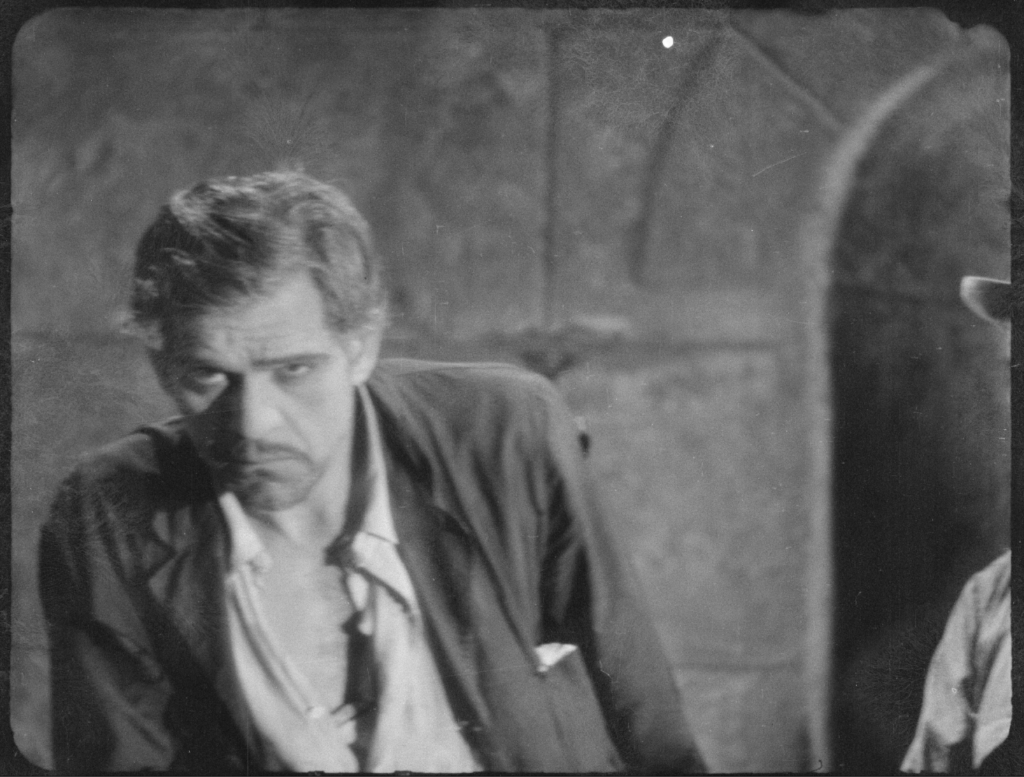

It’s also the first time Boris Karloff has dialogue in a sound film. It’s his second sound film, the first being Behind that Curtain, which came out about a month earlier, although he has no real dialogue in that.

I’ve been working on this since 2011, and I bought a print of the film in 1989! I have collected as many sound discs as survive on this one. The entire picture survives, but only some of the sound. Keep reading.

THE HISTORY:

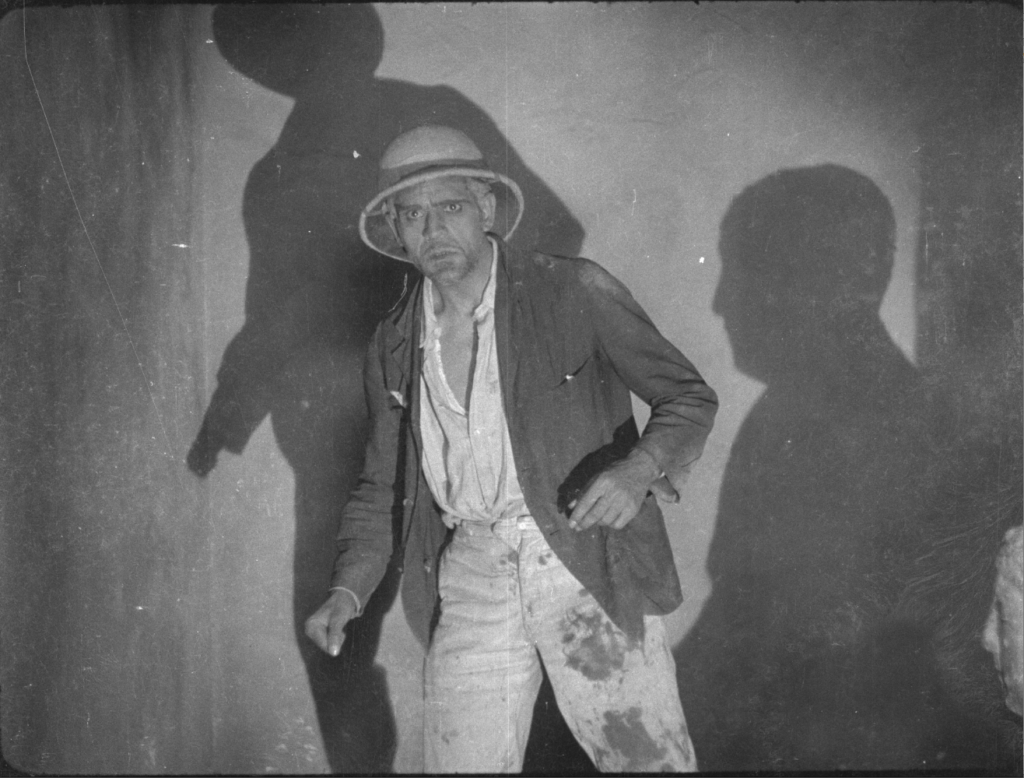

King of the Kongo was released in late summer 1929 to a lot of ballyhoo. It was released as a sound-on-disc only and it was called a “wild animal serial.” True to their word, there are lions, cheetahs, “gorillas,” “dinosaurs,” and elephants in the film. There was a silent version offered, but I have found no record that it actually played anywhere in the silent version.

In the 1950s, two collectors found a beaten up nitrate print with no sound discs and made a run of 16mm prints. I spoke to one of the collectors who made these prints. There are a few of these in private hands. I think there were only 5-6 made. I bought one of these prints. The lab work is, shall we say, questionable.

Several video companies released various copies of the film mastered from various prints in the 1970s and 1980s.

In 2011, I discovered that the print I had bought in 1989 was actually the sound version. I had only dimly considered it for a restoration project, but the curiosity got me to contact Ron Hutchinson, who sent me copies of several sound discs he had.

I did a Kickstarter to restore Chapter 5, and subsequently restored Chapter 6 and 10 with National Film Preservation Foundation grants. Each chapter is two reels (each reel lasting about 10 min), and there’s a talking sequence (about 2-3 min) in each reel. The rest of each reel is silent with a music and effects track. So far, the sound survives for about half the serial: Chapter 4 (one reel), Chapter 5 (both reels), Chapter 6 (both reels), Chapter 7 (one reel) Chapter 8 (one reel), Chapter 9 (one reel) and Chapter 10 (both reels). The script for the entire film survives.

As I was finishing up the work on the last of the NFPF grant work, word came to me that there was a stock film library that had the entire film in 35mm. Given that what I had was from beaten up 16mm prints made in the 1950s, the idea that there was nitrate was of some surprise.

THE CURRENT PROJECT:

I had been negotiating with the owner of the stock film library and the Library of Congress (where the stock film library is now held) since 2015. The length of time this has taken has led many to believe that I’m an evil hoarder who will never release this material. I just felt there wasn’t really cause to release what I had if there was a chance of getting better material, really four generations better than what I’d restored.

This year, I got all the details worked out, and we went through the whole film. In one state or another most of it survives in 35mm. We still have only 10 of the 21 reels of sound, but that’s not changed in several years.

The LoC currently has 47 reels of material on the film, and, amazingly, much of this is original camera negative! Given that this was a Mascot serial, later a part of Republic, the master negatives should have burned with the bulk of the Republic and Mascot material in the great Fox nitrate fire of 1937. Just how this survived is a mystery.

So we’re trying to restore the entire film with the best surviving material from each chapter, the best surviving sound material from each chapter, and using actors to recreate the missing sound.

WHERE WE ARE ON IT:

I am restoring the whole film at 4K right now. The Library of Congress is still in the process of scanning materials. I’ve only seen about 1/3 of the material so far. I have a grant that covers most of the cost of the actors and the blu-ray mastering, but the whole process at 4K is REALLY SLOW, and there’s a lot of damage in the film (keep reading). I’m hoping to have a release of this on Blu-ray in 2020. The grant I have is barely going to cover expenses, which means I’m going to have to do a lot of the work myself instead of farming it out while I do only the most critical work. This just means it takes longer, but it’s happening. FINALLY.

So far, I’ve rendered preliminary passes of Chapter 7, 9 and 10. I’ve discovered that there’s a section of Chapter 9 that’s rotted out and will have to be replaced from 16mm. Also, the surviving 35mm of Chapter 10 is missing the cliffhanger resolution and will have to be restored from 16mm. Even though we’re working from stunningly sharp negative on most of this, the negative is deteriorating. There are glue splices that are starting to rot and there’s flickery decomposition throughout most reels. I’m working with animation historian Steve Stanchfield to remove most of this, one more pass through restoration programs I wasn’t expecting.

WHAT I HAVE LEARNED:

This film really has some beautiful photography in it. This aspect of the film has been missing in the horrible dupes that have been available for many years. You can tell that some of it was shot on location and in a hurry in those scenes, so the lighting there is kinda hit or miss, but the interior scenes are very well done with some atmospheric lighting.

Some of the scenes in Chapter 6 were originally tinted! Pretty amazing. The negative has tinting instructions in it.

The temple scenes, credited with being shot at Angkor Wat in Cambodia, were inserted from camera negative shot in 1922 and 1927. These shots, by and large, are responsible for a lot of the deterioration. Apparently, producer Nat Levine just bought this negative and then had costumes made to “match cut” in with the footage of his actors shot in California. The closer temple shots in California are shot in some deteriorating building, and I think it’s a Spanish mission.

WHAT I AM HOPING TO DO:

I’ll have a restoration commentary on this (that seemed to work well on Little Orphant Annie), and I’d like to have some guest commentators on this so I’m not shouldering a three-hour yawn fest of me telling you that this is from print one or print six. I’ve contacted a whole swath of people and I’m hoping to have a number of them provide some good insights here.

WHAT YOU MAY HAVE HEARD:

There is another entity trying to release King of the Kongo on DVD/Blu-ray. They have been spreading bad will in social media and the collector network. If you have heard that I am hoarding material or if I am out after a cash grab on this for my own glory, this is not true. The actual answer is that I’m bordering on psycho for working on this as much as I have! I’ll be lucky to break even!

I don’t go for trashing other people in public forums, so I wish these guys well, and I hope they continue their work in restoring other serials. I have no idea why they are so upset with me, but it’s been pretty nasty in some circles. If they release King of the Kongo in their group, you have my blessing to buy it. Maybe they’ll have some cool stuff I missed.

No, I will not be working with them. Sorry, life is too short.