This is a real departure for the Dr. Film blog, and we’re not going to do this very often, but, well, just this one time.

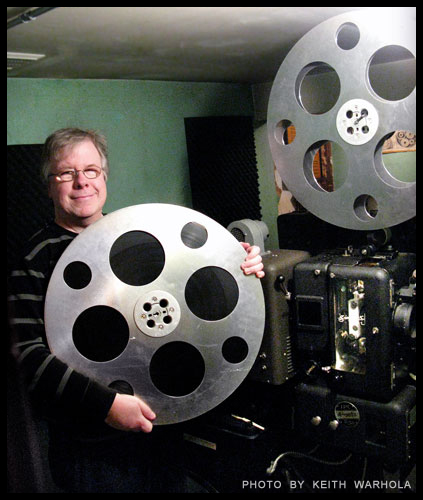

Here’s an interview between Dr. Film and his alter ego Eric, about Eric’s new book. If you haven’t followed the podcasts, Dr. Film is Eric’s utterly hostile, completely film-centric alter-ego.

Dr. Film: Hi, Eric, nice to see…er… be you.

Eric: Nice to be you, too.

Dr. Film: I hear you have a new book coming out.

Eric: Yes!

Dr. Film: Well, it’s about film, right?

Eric: Nope, not really at all. There’s only one section in it that has a film reference. It’s a joke, that only film geeks will get. It’s called “Pardon Me While I Have a Strange Interlude.”

Dr. Film: Then why are you wasting our time with something that’s not about film?

Eric: Because I already have an audience here, so I might as well.

Dr. Film: I see. So tell us about the book.

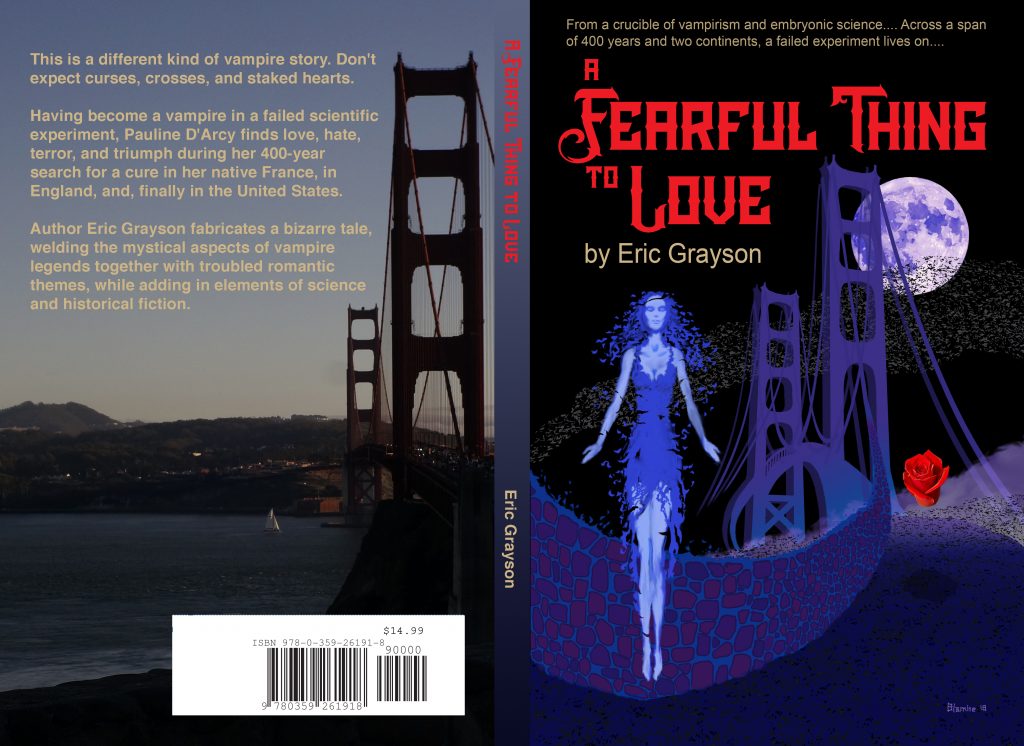

Eric: It’s called A Fearful Thing to Love. It’s a weird science-fiction/horror sort of story about a young woman who’s turned into a vampire. But not your standard vampire. It’s also a romance and sort of a science-gone-wrong story.

Dr. Film: Wow. So it could be a movie.

Eric: Well, I hadn’t thought of it as a movie. I suppose it could be. It would probably be expensive, since some of it is set in 2091, some of it during WWII England, and some of it in late 1600s France.

Dr. Film: So she lives a long time.

Eric: Yes, a very long time. It’s been compared to the Twilight Zone story Long Live Walter Jameson, by Charles Beaumont, but others have found elements of The Andromeda Strain and other things in it, except those aren’t about vampires and this is.

Dr. Film: OK. What made you write this?

Eric: I got tired of reading the standard vampire story about curses and evil and stuff, and all the religious trappings. I get that out of the way early in this one, and it doesn’t come up again. This is more like an unfortunate disease.

Dr. Film: How is it that people who have known you for years have never heard you talk about this?

Eric: Because there’s nothing more boring that an author talking about a book he hasn’t written, unless it’s a filmmaker talking about a film he hasn’t shot. People write you off really quickly; they can’t be part of your vision because they haven’t seen it. It’s like the people I used to see at Star Trek conventions asking me if they’d like me to read their story about Mr. Spock. NO! RUN!

Dr. Film: So is there a lot of sex and violence in the book?

Eric: Some. Not what you’d call a lot, and it’s not explicit, except some at the beginning. It’s more a character study and an exploration of ideas.

Dr. Film: OK, you have a female vampire, so that means we have to have lesbian scenes with hot chicks in it, right?

Eric: (looks at audience) I’m sorry, folks. He’s a politically incorrect idiot, but what are you going to do? I see that’s what you’re expecting. Well, this is written to go counter to your expectations. If you’re looking for Stoker or LeFanu, or even Hammer’s Countess Dracula, you’ll be disappointed.

Dr. Film: I’m trying for the hard sell and you’re making it tough here, dude.

Eric: Think moody, think more Outer Limits or maybe a lighter version of Charles Beaumont or Lovecraft, and you’ll be closer to what this is.

Dr. Film: Well, that’s something, I guess. How is it that you have time to do this with all your film work?

Eric: Good question. I didn’t. I get calls and emails all the time so it’s impossible to concentrate on something like this. I gave up writing seriously in about 1990 or so, because I just wasn’t producing the results I wanted. I worked on this during Thanksgiving, Christmas, and New Years for the last several years, the three days of the year that no one pesters me.

Dr. Film: What made you dig it up after all these years?

Eric: Easy answer. I’ve been pestered relentlessly by Glory-June Greiff, my co-conspirator on the Dr. Film show, to do something with this. She liked it better than I did.

Dr. Film: So does that mean you have more fiction writing that we haven’t seen?

Eric: Yes.

Dr. Film: What is it?

Eric: Let’s see how this one does.

Dr. Film: No hints?

Eric: No.

Dr. Film: A sequel to this one?

Eric: Not in the works, no.

Dr. Film: So this is a different sort of vampire story, written to counter your expectations. What else can you tell us about how it’s unexpected?

Eric: It’s deliberately structured to go counter to the standard English teacher way of laying out a novel. It’s not in 3 acts, but rather 5. And instead of escalating action and danger, it has less as the story progresses. And the last act is almost a comedy, with a happy ending.

Dr. Film: A happy ending in a vampire story? That’s weird. You’ve still disappointed me that there isn’t a lesbian scene in it.

Eric: I didn’t say there wasn’t a lesbian scene. There is one, but not with hot chicks, and there’s absolutely no sex in it.

Dr. Film: You have a lot to learn about marketing.

Eric: Spoken by the genius.

Dr. Film: Does this mean that you’re going to be doing less film work?

Eric: Not necessarily. It just means I’m not a one-dimensional cliche character like you are.

Dr. Film: I represent that. What sort of film work do you have coming up?

Eric: That’s more of a question for you, isn’t it?

Dr. Film: I suppose it is. Well, there are two projects that may be coming up soon, but I can’t tell you about them.

Eric: Yeah, I can’t either. But maybe soon. I had some time with no film projects and I put it into getting this and the podcast done.

Dr. Film: Those podcasts are cool.

Eric: Yeah, you would say that.

Dr. Film: We get a lot of requests to restore more film. Why aren’t you doing that?

Eric: Because our dear market isn’t strong enough to support the sales of these films, and a TCM sale fell through when Filmstruck collapsed. If I’d sold more copies of Little Orphant Annie, I’d be working on more film projects.

Dr. Film: So the fact that you’re doing this book is because you didn’t have enough work otherwise?

Eric: I suppose you could say so.

Dr. Film: Does that mean that you’re going to be polluting my sacred film space with promoting your junky book?

Eric: No, I would never do that to you. I know how it would hurt you. If I write a film book, then that’s another story. I’m planning one; it’s about halfway done.

Dr. Film: Well, is there a place that people can go to discuss this book?

Eric: I’m glad you asked. There’s a new Facebook forum for it. It’s here: https://www.facebook.com/graysontext/

Dr. Film: I feel better already.

Eric: I knew you would.

Dr. Film: Any other film tie-ins on this book? You know how I am about that.

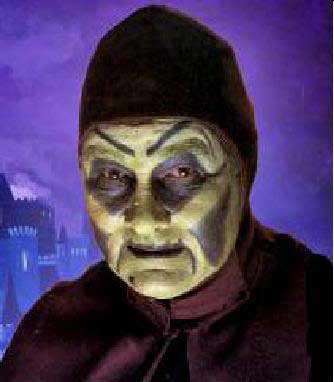

Eric: The cover art was done by Larry Blamire, the creator of the Lost Skeleton series, a talented director and author in his own right.

Dr. Film: Wow, so another hyphenate. But it’s a great cover.

Eric: It’s a fantastic cover. I may ask Larry if he can make small posters of it available.

Dr. Film: I think you should plug our new podcast again.

Eric: That’s a great idea. We’ve only been working on it since 2015. It’s here: podcast.drfilm.net.

Dr. Film: Available on most mobile and desktop services!

Eric: Well, we should wrap this up before it gets too boring.

Dr. Film: Too late.

Again, that book link is here: http://www.lulu.com/shop/eric-grayson/a-fearful-thing-to-love/paperback/product-23899576.html