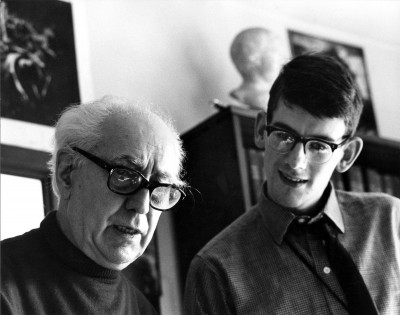

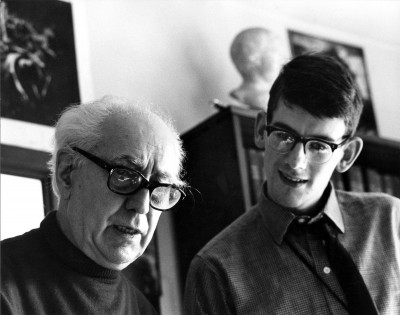

Kevin Brownlow (right), and Abel Gance (1967)

Seldom has a movie, particularly a silent film, been so enmeshed in legend and politics as Abel Gance’s Napoleon (1927). The French have their own restoration, there’s a different version at MOMA, and there’s yet a different cut made by Francis Coppola, who owns the rights to show it in the US. But the most famous, most complete version has been assembled by Kevin Brownlow, slowly, painstakingly, over the last 45 years or so. It hasn’t been shown since the 1980s in the US.

Attending a screening of Napoleon has become something of a Holy Grail. The few European screenings have attracted viewers from all over the world. The challenge of mounting a showing is daunting. The film is about five and half hours long, and it requires a screen for three interlocked projectors with a triple-wide ending sequence. Since it doesn’t have a recorded score, the film has an orchestral accompaniment written by Carl Davis, which he generally conducts himself. Just the thought of paying overtime and double overtime for the union musicians is staggering.

I was lucky enough to attend a showing in Oakland, California on March 31. It was spectacular. The theater was breathtaking, an art deco gem called the Paramount, absolutely gigantic, and painstakingly restored. I’d have gladly paid most of what I paid for admission just to look around the theater.

So what about the movie, you ask. Well, I’m getting to that…

I try to keep the Dr. Film blog pages from getting too saturated with film theory and technical jargon. I strive to have the blog full of film lore for geeks, but I also want to encourage newcomers. With this film, I have a problem. I can’t seem to discuss the movie without doing it in film geek terms.

The problem with talking about Napoleon is that it diverges strongly from most other silents. The differences between it and the run-of-the-mill silent films of the period can only be explained and illustrated by using fancy film terms. So I will apologize in advance to any newcomer who may be reading this. I hope it is still rewarding to any newcomer, but if you find if rough going, I recommend skipping forward to another one of my blog articles.

Napoleon is part of a rarefied class of films made by half-crazy directors who went wild spending money and had crews and producers that would support it. It requires a charismatic director so dedicated to the film that people will follow him into the abyss. In a very real sense the making of a film like Napoleon is like a Napoleonic campaign. Consider that Gance went to all the places that Napoleon did, with a similar sized crew/army, and prop ammunition, etc. The logistics are quite impressive.

Napoleon joins the rank of films like Intolerance, Metropolis, Lawrence of Arabia, Heaven’s Gate, 2001, The Adventures of Baron Munchausen, and a number of others. All of these have troubled production histories, bloated runtimes, maniacal directors, and out-of-control budgets. All of them are today considered at least minor classics, some major classics. Most of them were subjected to investor interference and extensive recutting.

I am saddened by the idea that many of the people who saw Napoleon did so without ever having seen another silent film. What makes Napoleon unique is that it uses a number of fascinating techniques. Some ideas were used years later, others not at all. To see Napoleon is to see one of the great experimental films ever made. There are parts of it that work brilliantly, other parts less so, but the ideas we see in this film are nothing short of staggering.

Consider these:

• Silent films tended to be cut with a slower rhythm that modern films are. Gance has several sequences in Napoleon that are cut with lightning speed, just as fast as a modern Michael Bay film. Gance had the intelligence to use this technique sparingly, so that the confusion of “chaos cinema” used in action sequences today is minimized. What does happen is that we get the effect of being “in the fight” while still clearly understanding what is going on.

• A brilliant little sequence uses a technique I’d never seen before. Napoleon sees Josephine and finally gets a chance to meet her properly. He’d met her briefly a number of times before. Gance gives us a closeup of Napoleon, and then flash cuts of their other meetings, and then back to Napoleon reacting. In the space of a second, we understand what’s going on in Napoleon’s head as he works this out. Amazing technique. No flashbacks, lap dissolves or anything. The only other time I’ve ever seen anything like it is during a scene toward the end of Charade (1963), but that usage is fundamentally different and is actually cut slower!

• Moving camerawork was difficult in 1927. Film stock was slow, which meant that a lot of light was required to keep anything moving in focus. Furthermore, most cameramen were using hand-cranked cameras, which naturally limited mobility. Gance gleefully breaks all convention here. Motorized cameras, handheld camerawork, cameras on seesaws, on wires to create smoother shots. It all looks rather seamless and more like some of the work we see today with Steadicams and the like. Gance had no such things. Perhaps the Germans were doing a bit more with the moving camera at this time, but Gance integrates it wonderfully into the film, less as a stunt and more as a real storytelling device.

• Gance’s Polyvision, with three interlocked cameras, used at the end of the film, is amazing. Gance could have met with Henri Chretien, creator of the Hypergonar process that eventually became Cinemascope. That would have given him the widescreen process he craved. What he came up with was equally brilliant. The interlocked projector technique, which he called Polyvision, is extremely similar to Cinerama, which debuted publicly in 1952. But even here Gance does things differently. Cinerama always apologizes a little for the join lines between the panels, trying to minimize them as much as possible. Gance embraces the whole idea. While Cinerama always used single shots (the same scene spread across each of the three screens), Gance will happily have a different shot on each screen, or a mirror of the right screen on the left screen. Sometimes Napoleon will be seen in closeup in the center panel while a long shot is seen on the side panels. This would never have been done in Cinerama! At the end of the film, he even tints each screen to match the French flag in a sequence that is as bravura a piece of filmmaking as I have ever seen.

Is it excessive? Sure it is. That’s the whole point. If I can make an analogy that’s used frequently, Gance starts Napoleon like an organ with all the stops pulled. You’d think he had nowhere to go. What he does is to effectively build more stops through the end of the picture and use those. Yes, it is wearing, and yes, there are sequences that are so long that any producer would scream to cut them back.

That’s why I can understand why people have wanted to cut Napoleon down to a manageable size for years. Gance himself recut it and recast it with sound. He remade it with sad results. But if we look through history, Intolerance was long and was recut. That was DW Griffith’s picture, one of the directors Gance revered. Metropolis was recut extensively. 2001 was recut. Brazil was recut. Lawrence of Arabia was recut. Each of these films was long and excessive, made by an obsessed director.

Again, that’s the point.

This is why I laud Kevin Brownlow for restoring Napoleon as it was. He’s fought the good fight against recutting it to fit modern tastes, to fit cinema runtimes, to anything other than the best we can approximate Gance’s vision. This is why that, to this day, Napoleon still stands out from the crowd. It’s not commercial. It never was. It’s not like any other film, silent or sound. It wasn’t intended to be. It is what it is. Even Coppola’s cutting and speeding-up of Napoleon, which was intended to minimize the overtime for the musicians, compromises Gance’s vision.

Napoleon felt, to me, a lot like a David Lean film (Lean, director of Lawrence of Arabia.) It also had a strong influence from DW Griffith (Intolerance) in terms of narrative structure and editing. But it also had an avant garde feel.

The acting was brilliant, particularly Albert Dieudonné as Napoleon. Davis’ score was an inspiration, based on pieces of music from each period in Napoleon’s life. The theater, presentation, and ambience were all top notch.

Out of all the brilliance of the evening, I still need to single out Kevin Brownlow. I wouldn’t call soft-spoken Mr. Brownlow obsessive. I would call him dedicated to doing the right thing. He’s suffered slings and arrows for years from people who didn’t care to have Napoleon restored.

I give him a special tip of the Dr. Film fez. Without Kevin Brownlow, we’d be missing a key piece of movie history. It’s a glimpse of a cinema that was, a cinema that never would be, and a cinema from the mind of a genius.

A still from the triptych: look carefully, and you can see where the 3 images join

Special side note: Much was made of the idea of putting Napoleon out on DVD or Blu-ray. I, for one, hope it never is. What I hope for is a well-publicized successful roadshow of the film in major cities across the US. I know that theatrical exhibition is passé today. I still think Napoleon should be seen in a theater, with an audience, and if possible, with a live score. Brownlow mentioned that Stanley Kubrick wanted to borrow a print of Napoleon to watch on his flatbed viewer (a small-screen device used for editing films.) He told Kubrick that this was a bad idea, given that the film lost most of its impact on a small screen.

“It’s like watching Lawrence of Arabia on a phone,” Brownlow said. (Mind you, I believe Mr. Brownlow would happily release the film on DVD just to get it out there for people to see. It is my own opinion, not his, that it shouldn’t be on video.)

For the record, I won’t watch Lawrence of Arabia on anything but a big screen, and I think Napoleon deserves the same respect.