When I was a kid, growing up and watching movies on TV, I read about Lon Chaney Sr., in the magazines of Forrest J. Ackerman. Ackerman (1916-2008) was a great friend of Ray Bradbury and Ray Harryhausen. As of Mr. Bradbury’s death today, Harryhausen (1920- ) becomes the last survivor of the long-lived group.

Ackerman always praised Lon Chaney and claimed he was a special actor, whose like is not to be seen today. Even as a nine-year-old, I wanted to see more of his films. In those days, most of Chaney’s pictures were impossible to see. If you were very lucky, you might see a chewed-up print of The Phantom of the Opera or The Hunchback of Notre Dame. It was unlikely that you’d see any of the other ones.

As video came to the world, I got a slow trickling of Lon Chaney movies. I was a teenager at the time. I was mesmerized by him. What an actor. Ackerman was right.

Then, many years later, I attended a lecture at Butler University with Douglas Adams and Ray Bradbury, two authors who could hardly be more disparate, but were both typecast (if one may use that word for an author) as “science fiction guys.” This, as Harlan Ellison would tell you, is considered by the literati to be one small step up from porno authors and men’s room attendants.

Adams came on and was enchanting. He read excerpts from his Hitchhikers’ Guide books, and some other things. He was a natural-born actor, able to put a spin on his work like no performers I had ever seen before. I loved every moment of what he did, and since he died not long after, I’m glad I got the chance to see him in person.

Then Bradbury came on.

By this time in his life, had had a stroke, and was stuck in a wheelchair. His speech was somewhat impaired. His ability to move one hand seemed to be a little strained.

I realize that everyone will focus on Mr. Bradbury’s literary accomplishments, which are legion, in celebrating his life. I don’t want to take anything away from that at all, because I love Bradbury’s work. But there was another side to him, as a lover of film, and since this is a film blog, that’s what I want to cover here.

Bradbury called films “wonderful” and “magical,” and he wanted nothing to do with the idea that they were somehow low-class art. He’d worked on many films himself, including the underrated Something Wicked This Way Comes (1983) and Moby Dick (1956). He did a fantastic impression of director John Huston when he spoke of the making of that picture.

He went on to talk about his favorite star when he was growing up. Born in 1920, Bradbury was an impressionable child just as Lon Chaney was becoming a big star. In those days, it was fairly easy to see movies reissued, so even as a youngster, he was able to see most of Chaney’s big pictures in reissue.

Chaney, he said, was able to reach into his soul and find something in some of these characters that was human and touching, despite how horrible they often were. Bradbury often teared up a bit when talking of Chaney’s work, and how emotional it made him.

Of course, most of the audience had no idea what he was talking about. After all, Chaney has been dead since 1930, and he only made one talking picture. Even today, a good bit of his silent material is difficult to see and a fair chunk doesn’t survive at all. But I had seen it! I knew exactly what he meant.

One of the things that always annoys me in an interviewer is when they ask me, “Can you name an actor today who is like this silent star we’re discussing?” Well, no. Lon Chaney was unique in cinema. There was no one ever like him, and there likely never will be again. Despite the fact that some of his movies were clichéd and hammy, with hare-brained plots and weak direction, Chaney was always able to wring something worthwhile out of them.

He was so good at certain things that he got tagged with them and had to do them over and over again. Weird, contortionist makeup? He was great at it. Playing disabled characters with deformities? No one better. Ethnic types? Chaney’s your man. And the thing that tied them together: No one, no one ever, was able to convey the emotions of traumatic disappointment and utter heartbreak like Chaney did. One facial expression. You felt his pain. The man was a genius.

It was almost a given that Chaney didn’t get the girl at the end of the picture, but he sure tried and it killed him (sometimes literally) that someone else ended up with his love. I often find that some of Chaney’s best performances are in his most conventional parts, like Tell It to the Marines (1926) or While the City Sleeps (1928). But Chaney could still play convincingly through thick makeup. Even a fairly conventional picture like Shadows (1922) features Chaney playing an 80-year-old Chinese laundryman. It is hard to see the 39-year-old Chaney in the part. After a few minutes, we simply believe he is that character.

As I continued to listen to Bradbury, it occurred to me that much of his work was colored in the same way that Chaney’s had been. No, not science fiction, not horror, not claptrap. Chaney was all about emotion. Often it was about a alienated person who didn’t really fit in with the rest of society. Bradbury’s work was too.

I remembered that in high school we’d been assigned to read 1984 and Fahrenheit 451. I know that the “English teacher mentality” taught that 1984 was a timeless classic. I felt at the time that Fahrenheit 451 was much more interesting, because it had passion that I never felt at all in Orwell’s novel. Bradbury’s characters deeply loved a history that society was taking away, so much that they were willing to die in order to preserve it.

It was a very Lon Chaney sort of idea.

Bradbury was moved to tears again as he recounted Chaney’s untimely death in 1930, and how it affected him personally. This man, his hero, was dead! It could even happen to someone like Lon Chaney! It made the ten-year-old boy shudder at both Chaney’s mortality and his own.

We are fortunate that Bradbury lived over 90 years, just as we are unfortunate that Chaney never reached 50. Tonight I celebrate the legacy of both men. I hope somewhere, somehow, The Man of 1000 Faces gets to meet the creator of The Illustrated Man.

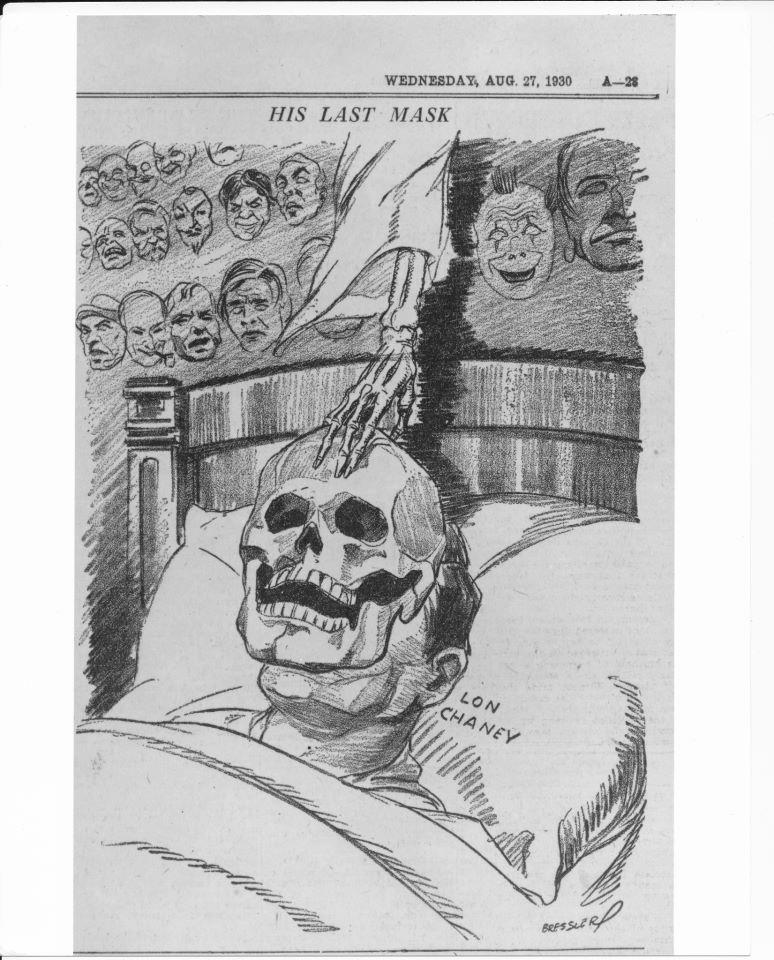

As a postscript: I have seen an artist’s picture, which I cannot find, of Death laying the final mask on Lon Chaney’s face. I can think of no better image to include here.

Post postscript: (added 8/26/12). Michael Blake found the picture, which I am including here.