Dr. Film readers: I wrote this for another blog as a guest, but they didn’t use it. But I can’t just trash a useful blog posting, so you get to read it now!

People from Generation Y, often called Millennials, are being lumped into a group by our media. They are said to have a core belief that modern cinema began with Star Wars: Episode IV (1977), and that any movie older than that is culturally irrelevant. Under these conditions, it becomes difficult to make a case that 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968) is still culturally relevant at all, since it is much older and depicts a future now 12 years past. Even though it may seem a distant relic, 2001 is still a stunning and fresh experience.

The vast majority of films that try to depict the future, particularly anything with a science fiction slant, fail miserably both in dramatics and accuracy. Fritz Lang’s Metropolis (1927) shows a bleak world of labor unrest and a severely divided culture. HG Wells’ Things to Come (1936) foretells a second World War that is stunningly accurate, but Wells’ war lasts for 30 years and degrades into global tribal conflict, a worldwide Afghanistan. The triumphant moon landing does not occur until 2036 and is technically incorrect in almost every way.

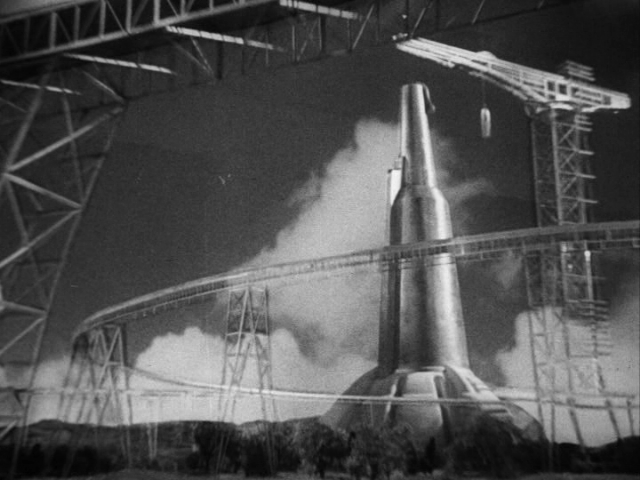

Learning from his mistakes in Metropolis, Fritz Lang tried again with Woman in the Moon (1929), which is amazingly accurate up until the rocket lands on the moon. This is, no doubt, largely because Lang hired advisors from the scientific community, many of whom went on to work on the German V-2 rockets and, later, the American Apollo program. Similarly, producer George Pal hired only top people for his Destination Moon (1950), which, despite some very hokey dramatics, holds up pretty well.

But 2001 is in a class by itself, and always has been. Novelist Arthur C. Clarke simply projected the American space program forward into the future, making the assumption that we would maintain a constant level of funding. That was his only major mistake, because the Apollo program was not the beginning of a slow ramp of progress, but a bubble of innovation in a sea of lethargy.

2001’s gleaming spaceships, rotating space stations, and moon colonies never came to pass, not because they were impossible or impractical, but because we did not care to pursue them. Where Lang and Wells had been overly pessimistic and lacked technical vision, Clarke and director Stanley Kubrick miss the mark only because America decided to cut back space exploration.

Kubrick employed groundbreaking techniques at every point in 2001. It was the first time in history that a movie based in space was truly convincing. George Pal’s 1950s epics had come close, as did Forbidden Planet (1956), but 2001 topped them all. It was the start of a career for Douglas Trumbull, who has continued as an innovator in the field of special effects.

After 2001’s triumphs, the movie industry went back to doing cheesy, unconvincing special effects, simply because it was too expensive to do them the way Kubrick had done. It was easier to invoke the spirit of Flash Gordon with ray guns and buzzing rockets than to do the stately effects that Kubrick produced. 2001 represents a gigantic step sideways, out of the mainstream of cinema. It was not until George Lucas made the process more economical with computer-controlled model work that the same degree of conviction came back to movies. Lucas managed to combine the fun of Flash Gordon with the more convincing feel of 2001, and he did it without being a budget buster.

From a dramatic standpoint, 2001 represents another giant step sideways, a step that has not been replicated. Kubrick strove to make his film visually engaging with a minimum of dialogue. At many points, Kubrick’s directorial technique recalls silent cinema. He challenges the viewer to keep up with the story. It is not brainless and transparent in the way that many comic-book movies are today. 2001 demands constant attention and participation from the viewer.

2001’s uniqueness in film history does not make it culturally irrelevant. The film depicts many key innovations that did come to pass. Scientist Heywood Floyd (William Sylvester) flies to the moon in a shuttle not dissimilar to the later space shuttle. He makes a video telephone call to his family. Astronauts Poole and Bowman (Gary Lockwood and Keir Dullea) use computerized tablets that parallel modern iPads. In fact, the similarity has been used as a complex legal defense in a lawsuit between Apple and Samsung (http://io9.com/5833739/samsung-uses-2001-a-space-odyssey-as-prior-art-in-apples-ipad-lawsuit)

We still have no modern computers that talk and interact like HAL, voiced by Douglas Rain. Rain’s creepy, emotionless delivery is one of the most memorable in the history of cinema. It was the inspiration for Anthony Hopkins’ eerie portrayal of Dr. Hannibal Lecter in The Silence of the Lambs (1991). Apple’s new Siri functionality on the iPhones comes closest to HAL, but Siri hardly seems as threatening as a room-sized computer that controls all of the life-support systems in a gigantic spaceship. Siri also bumbles and misinterprets in a way that HAL never did.

Ironically, HAL has the greatest amount of dialogue and screen time of any of the characters in 2001. Many of the humans are denied closeups and establishing stories, making 2001 feel cool and distant toward most of its key characters. The story is not about individual humans but about the larger class of humanity itself. It is HAL’s conflicted view of humanity that causes the plot to move forward. The mysterious monoliths seem to nurture and encourage humanity to go off and pursue new horizons.

Ultimately, 2001 is not outdated, but simply a story of a future that never occurred. Its use of sparse dialogue and deeply technological themes foretells a cinema that never occurred, or an alternate universe. After more than 40 years, there still is no other film quite like 2001.