I was having a discussion, a polite one, with another film historian the other day. He’s a guy I like and respect, so I won’t sully this conversation by naming him, because I disagreed with his whole premise. That’s OK, because he disagreed with my whole premise.

To sum up, this was his position:

Comedians other than the “Big 3” are only of academic interest and should not be shown to general audiences. General audiences are so far removed from the days of silent comedy that they can no longer relate to it in any way and shouldn’t be asked to. The whole idea that we have the “Big 3” is because the critics have decided that these are the best and most worthwhile comedians to watch, and therefore any uninitiated audience should see them first. The other comedians should not be run for first time audiences because they are not as good and unique as the “Big 3.”

The Big 3, of course, are Chaplin, Keaton and Lloyd. Some people will call it the Big 4, including Harry Langdon.

Now I’ll sit here right now and tell you that I have absolutely NOTHING against Chaplin, Keaton, Lloyd, or Langdon. I like them, every one.

But I hate this idea to its very roots.

I have this strange and odd counter-idea. I think comedy should be run because it’s funny. And I have another strange and odd idea: I don’t believe that there is a Jeffersonian Meritocracy of comedians and that we’ve decided who the good ones are and who the less worthy ones are. There are just plain too many films that we haven’t seen to judge accurately.

I’ve pointed this up before, but I have to say it again: films don’t necessarily survive and get shown because they are good. They survive and are shown because they are available, out of copyright, and can be found in nice-looking prints. Film history is written by the survivors, not necessarily the best films.

This whole notion got started in Walter Kerr’s book called The Silent Clowns. Now, again, I don’t have a problem with Kerr, either. My problem is that he wrote his book in 1975 when it was just downright impossible to see a lot of the films that we take for granted today. In 1975, we could say that DW Griffith was the father of film, because everything we could see showed Griffith streets ahead of everyone else.

Now we see that this wasn’t true, that there were others who were doing really interesting work. It was the fact that Griffith’s films were seen and preserved that put him in such a hallowed position. And, again, Griffith deserves a hallowed position, just not as the only guy who made movies move forward.

In 1975, there were only a few Charley Chase films available, almost no Max Davidson around, no Charley Bowers at all, and not even all of the Keaton and Lloyd films were obtainable. The Langdons were spotty. Kerr had to rely on memories and prints that he could find in private collections (thank you, Bill Everson.)

Arbuckle? Not much. Lloyd Hamilton? A few. Snub Pollard? Hit and miss. Lupino Lane? Never heard of him. Larry Semon? Yeah, there’s some stuff around.

And that’s only the tip of the iceberg to me. I don’t think we should look at Kerr’s book as the roadmap for “this is all we should watch” because he studied it and wrote the book for us. In my opinion, he’s telling us, “Hey, I’ve studied these films, these are some of them that I like, and here’s why I like them.”

That’s valuable, and that’s why the book is great. But if we limit ourselves only to what he covered, it’s a sad thing. It’s like eating only Big Macs at a Smorgasbord. Hey, Big Macs are popular, some of the most popular food in the world, nothing wrong with them. But you can find those anywhere, and there’s so much other stuff you could try… even just to nibble on!

I would also make an argument that limiting ourselves to these guys is sad on another level. Chaplin, Keaton, Lloyd and Langdon all had an interesting commonality: they had almost complete control of their pictures and basically unlimited budgets. Chaplin even had almost unlimited time.

Is it really fair to compare Chaplin, who made one movie in 1925, to Charley Chase, who made 19 movies in 1925? I’d wager that all of Chase’s movies together cost less than Chaplin’s one. Does that make Chase a lesser comedian, or Chaplin a better one?

WHO CARES? Chaplin is funny and so is Chase, and there’s not a fair benchmark to compare them. Want some laughs? Watch Chase in His Wooden Wedding. Chaplin? Well, you know about him already. At least I hope you do. Otherwise, watch The Gold Rush.

The guy that I’d like to see analyzed by the academic types is Larry Semon. This guy was insanely popular in the 1920s, his movies made money, he had a great following, and his own studio. And his movies are interesting but not very good when seen today. It is fair to pit Semon against those other guys, but for some reason, no one does.

And we do other odd things. The Big 4 are to be revered because they came up with individual comic characters, when no one else did. Seriously?

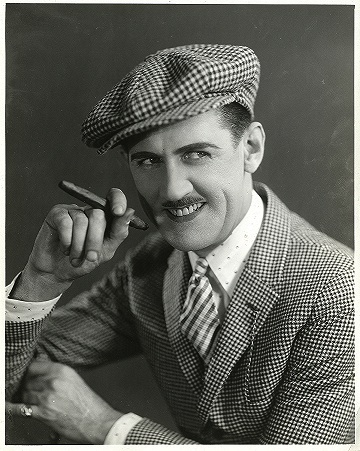

Chase had a unique character, and we can now see him build into it. Then, when talkies came in, he became too old for the man-about-town-misunderstood-husband, and he changed the character. Max Davidson had a unique character, quite unlike anyone who has come before or since.

Chase had a unique character, and we can now see him build into it. Then, when talkies came in, he became too old for the man-about-town-misunderstood-husband, and he changed the character. Max Davidson had a unique character, quite unlike anyone who has come before or since.

Oh, but Max had help, you cry. Leo McCarey and George Stevens worked on his films. Yeah? You think those other guys didn’t have brilliant writers? Clyde Bruckman worked with almost all of them at one point.

Apparently, Arbuckle, who invented a lot of things that got ripped off later, isn’t a genius because he didn’t last long enough into the 1920s, even though he did a lot of directing after the scandal that unfairly sidelined him.

Lupino Lane was too British and was willing to use special effects in conjunction with his amazing acrobatic abilities, so that negates him.

Charley Bowers doesn’t count either because he used extensive special effects, and didn’t have a unique comic character. It was just a ripoff of Keaton, according to those who are “in the know.”

Seriously?

I have two criteria for judging comic performers:

- is it funny? Does it make me laugh?

- is it stale? If I’ve seen it before done by someone else, then I’m not too impressed, and even less so if you don’t do it a lot better than I saw it the first time.

By this yardstick, I officially love Keaton, Chaplin, Lloyd, Lupino Lane, Max Davidson, Charley Chase, and Charley Bowers. And a lot of other comedians, too.

Let me make a slight sidelight for two of them. As many of you know, I’m a sucker for something different, something I’ve never seen before. I really hate boring predictable movies, especially if they’re comedies.

This is why I especially love the silent comedies of Max Davidson and Charley Bowers. Lupino Lane is great too… but he’s an acrobat with a great sense of timing and danger. It’s familiar stuff done fantastically well.

But Bowers. Wow. I disagree completely with the dismissal that he’s part Chaplin and part Keaton. (He actually looks a little like Keaton, which isn’t his fault, but it’s led to his being dismissed as an imitator.) Bowers is all Bowers. He is a reality-challenged go-getter (actually rather more like Lloyd than the other two) who solves problems in ways that no one ever thinks of. There It Is (1928), which is probably his finest surviving silent film, is so bizarre as to be beyond description. Now You Tell One (1926) has some of the most haunting ideas I’ve ever seen in a film: Bowers marches elephants into the Capitol Building, and has invented a grafting potion that allows any item to grow from a stem: cats grow from cattails, eggplants sprout eggs, etc. The sheer volume of ideas that strike Bowers is enough for me to love him.

But Bowers. Wow. I disagree completely with the dismissal that he’s part Chaplin and part Keaton. (He actually looks a little like Keaton, which isn’t his fault, but it’s led to his being dismissed as an imitator.) Bowers is all Bowers. He is a reality-challenged go-getter (actually rather more like Lloyd than the other two) who solves problems in ways that no one ever thinks of. There It Is (1928), which is probably his finest surviving silent film, is so bizarre as to be beyond description. Now You Tell One (1926) has some of the most haunting ideas I’ve ever seen in a film: Bowers marches elephants into the Capitol Building, and has invented a grafting potion that allows any item to grow from a stem: cats grow from cattails, eggplants sprout eggs, etc. The sheer volume of ideas that strike Bowers is enough for me to love him.

And there’s nothing like him again in all Cinema.

And Max Davidson. Oh, Max. I’ve come to really love Max as an actor because he pops up in movies all the time. A shock of hair, a beard, but an amazingly flexible face that can even portray policemen if necessary. As a cheap Jewish character, Max got his own series along Chase and Laurel and Hardy in the late 20s. I love Max’s reaction shots. Max’s reaction to the chaos that often surrounds him is priceless. He’s every bit as good (and different) as Babe Hardy was at portraying frustration or just plain bewilderment. Pass the Gravy (1928) hinges on him not understanding a key element of the plot for 15 minutes, and he absolutely sells the idea that he doesn’t follow it. The guy sells a one-joke comedy for 15 minutes, and it’s one of the funniest films I’ve ever seen.

And Max Davidson. Oh, Max. I’ve come to really love Max as an actor because he pops up in movies all the time. A shock of hair, a beard, but an amazingly flexible face that can even portray policemen if necessary. As a cheap Jewish character, Max got his own series along Chase and Laurel and Hardy in the late 20s. I love Max’s reaction shots. Max’s reaction to the chaos that often surrounds him is priceless. He’s every bit as good (and different) as Babe Hardy was at portraying frustration or just plain bewilderment. Pass the Gravy (1928) hinges on him not understanding a key element of the plot for 15 minutes, and he absolutely sells the idea that he doesn’t follow it. The guy sells a one-joke comedy for 15 minutes, and it’s one of the funniest films I’ve ever seen.

And there’s nothing like Max again in all Cinema.

I suppose I should sum up by saying that there’s nothing wrong with watching only the big 4 comedians. I like them all. But there’s so much more out there today, stuff that’s funny, stuff that does stand up to the test of time, and if only watch the big 4 you’ll be missing it, along with a lot of laughs.

You can still get a Big Mac at the Smorgasbord, but there’s a McDonald’s on every street corner all around the globe. Wouldn’t it be fun just to taste a spanakopita from Greece? I love them, too. Think what you might be missing.

Don’t take my word for it. Your tastes may vary. Find out for yourself, and get back to me.