I remember a play I was in many years ago. I was playing a Supreme Court Justice in First Monday in October. One of the main questions in it concerns an obscenity case in which the justices are called upon to decide whether a particular porno movie is so obscene that it cannot be shown. The justices all gather together and watch the movie, except one.

The holdout justice insists he doesn’t need to see the movie. He’s voting for it to be shown, no matter what. He feels that the First Amendment is sacrosanct and any chipping at it lessens us all.

Amen!

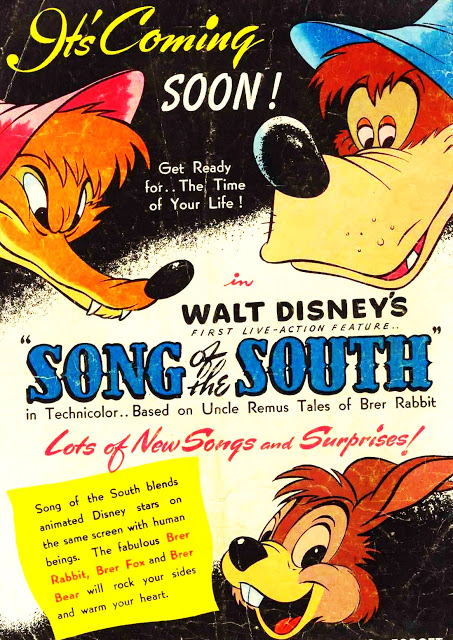

There’s been a lot of hubbub on one of the movie collector forums about Disney’s Song of the South (1946). This is one of the few films Disney has never released on home video… well, one of the few popular color and sound films. I’ve never seen it. Its last theatrical release was a rather sparse one in 1986.

And the cries come out against it: “It’s racist.” “It’s antiquated.” “It would offend people.” “We shouldn’t show it in case it does offend people.” “It’s not a great work of art, in part because it’s offensive.”

I never understand this stuff. It cuts across political barriers, too. Basically, the criterion for banning something is “I don’t like it.” Books, movies, music, you name it, someone wants to ban it. It’s often in the name of “the children.” We wouldn’t want to expose children to this sort of thing, would we?

Let’s look at what this is, instead of our opinions about it:

James Baskett won an honorary Academy Award for the film.

Oscar winner Hattie McDaniel appears, the first African-American woman ever to win an Oscar.

Walt Disney considered Baskett a discovery, one of the best actors he’d found.

The work with animated characters superimposed over live action is groundbreaking, especially in a color film (this was shot with the three-color Technicolor camera.)

It’s one of the last works of legendary photographer Gregg Toland, the cinematographer of Citizen Kane.

Is there racial stuff it it? Sure. Is it insensitive by modern standards? I have no doubt it is.

Should parents plop their kids in front of it without explaining it to them first? NO! But that goes for a lot of stuff. The television is not an electronic babysitter, nor is the iPhone or any other device. Sure, there’s a lot of mindless stuff out there that can just be watched, and this isn’t one of them.

I haven’t seen Song of the South. I don’t need to. It should be out there to be seen. If we have to get Leonard Maltin, Whoopi Goldberg, or Bill Cosby to do an introduction, then fine. It should be seen.

This reminds me of an interchange I had with a friend of mine who I’ll only identify as “Chef Carl.” I was asked to come up with a program for Black History Month. OK, I said, let’s show how racism once rocked the movies. Let’s really show it. I had some good examples. They wouldn’t let me do it. The manager of the theater said it would be perceived as insensitive because I’m white. OK.

So I thought about all the African-American folks I know and thought, “Who’d be the best one to introduce these pictures and explain the history of them?” I thought of Chef Carl. He even agreed to do it. Then the manager came forward and wouldn’t allow Carl to do it either. Why? Well, they were afraid that Carl would be seen as a “token black,” which was bad, too. I told Carl about it. I still remember his answer:

“So you can’t introduce the movies because you’re white and I can’t introduce them because I’m black.” BINGO. The most accurate response I can imagine.

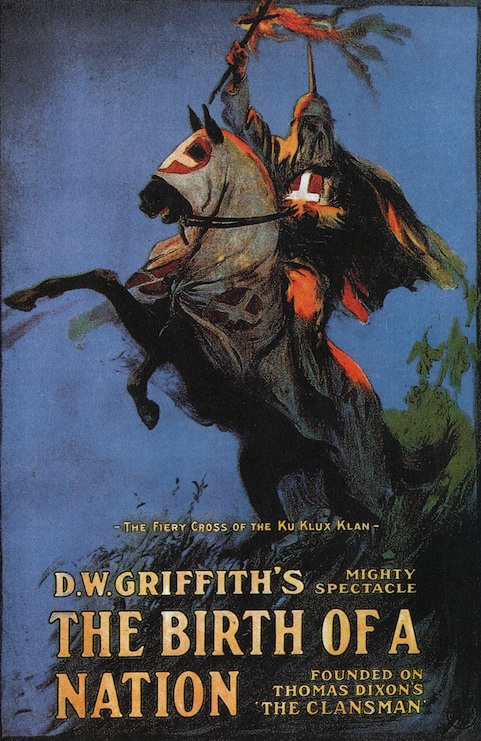

There’s a similar uproar with Birth of a Nation (1915), which is a DW Griffith film. Birth of a Nation changed the world. It was the first time that it was clear that a long, feature-length film could make money and keep making money. It caused the landscape of movies to change. Vaudeville houses switched over to movies. Movie houses changed from flat Nickelodeons to raked, long theaters. Theaters put in extra projectors to make smoother changeovers. It was a big deal, and it made money in the North and South, wherever it played. It’s a good film, it’s a landmark film, and it’s one of the key films in the history of the motion picture.

There’s a similar uproar with Birth of a Nation (1915), which is a DW Griffith film. Birth of a Nation changed the world. It was the first time that it was clear that a long, feature-length film could make money and keep making money. It caused the landscape of movies to change. Vaudeville houses switched over to movies. Movie houses changed from flat Nickelodeons to raked, long theaters. Theaters put in extra projectors to make smoother changeovers. It was a big deal, and it made money in the North and South, wherever it played. It’s a good film, it’s a landmark film, and it’s one of the key films in the history of the motion picture.

It also sparked a resurgence of the KKK in America. There was a lot of racist content, and one of the Klansmen is a hero. It was true to the book it was based on, which was also racist. Without even really understanding what he did, DW Griffith made a racially polarizing film in 1915. It was so polarizing that he got death threats and there were Klan rallies that showed the film to whip up support for a new (and very different) Klan.

Griffith (a child of Kentucky) felt so awful about the film’s reception and what it did that he made a followup called Intolerance (1916) that made the age-old plea of “Why can’t we just get along?” Just how racist Griffith himself was is the stuff of much speculation. I can simply state that Madame Sul-Te-Wan (1873-1959) a long-lived African American actress, appeared in Birth of a Nation. There’s also a reel of home movies shot at DW Griffith’s funeral in 1948. She’s in that reel, too, crying and needing support from others, the only person in the whole reel who seemed to be moved at the occasion.

If DW Griffith was the evil, racist pig that many modern authors make him out to be, then why was Madame Sul-Te-Wan so moved at his funeral? She knew him… we didn’t.

Shouldn’t we see the film for ourselves to find out? Or, if we choose not to, shouldn’t we be free in that choice, too? There have been protests at showings of Birth of a Nation even as recently as a few years ago, rife with cries of “It should be banned!”

No, it shouldn’t. The surest way to perpetuate an idea is to try to stamp it out. I’ll repeat that, and it’s key: The surest way to perpetuate an idea is to try to stamp it out.

Let me give you an example of what I’m saying. When FW Murnau made Nosferatu in 1922, he stole it from the novel Dracula. Let’s be honest, he stole it. They changed all the names around, but the plot is barefaced and recognizable. The book was very much in copyright and Murnau was sued. The studio lost, and the film was ordered destroyed. All prints, and the negative, too.

Except.

Nosferatu became forbidden fruit! Film pirates the world over clamored for “the last print.” There were a lot of “last prints” saved, duped, and bootlegged. It got way more release in foreign countries than any of other Murnau’s films did. He became a popular director mostly because of the fame of a movie that no one was supposed to see.

So consider Der Januskopf (1920). This was another FW Murnau film pirated illegally from a novel and play. In this case it was Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde by Robert Louis Stevenson. It became Janus-kopf (Janus head) and the two characters were Dr. Warren and Mr. O’Connor. The dual role was played by Conrad Veidt. Veidt’s butler was played by Bela Lugosi, who was on his way from war-torn Hungary to America. This is one of his few appearances in a German film.

Historically important? You bet. But no one sued over this film, and there was no clamor over its illegal piracy. No one bootlegged the last prints or the negative, which stayed in storage until it rotted.

Two films, one director, both pirated, one forbidden fruit, and one completely legal. The forbidden fruit survived. Stamping out the idea perpetuated it. Today, you can get a version of Nosferatu on any street corner, in various versions, cuts, tints, and speeds.

And is that different now? Nope. Song of the South is forbidden fruit. It’s out there. As of this writing, there are 85 copies on eBay for sale. Those are just the ones who are brazen enough to post them.

Just 10 copies of Steamboat Willie for sale, though. That one… it’s always been available. It’s a landmark Disney picture, the first cartoon with sound, the first big Mickey Mouse picture, and 10 copies.

So is Song of the South a great film? I have no idea. I might like it, I might not. I might be offended, and I might not. My advice to Disney is to make it available and therefore control the dialogue about the film. Now it’s forbidden fruit. You can make it a “Never Forget” historical item, which it needs to be. You can also make sure that everyone knows why it’s historically important.

By the way, I don’t want political comments in the comments section or I’ll shut it down. “Those liberals” and “Those Republicans” are equally guilty of censorship, albeit often for different reasons. This isn’t a political forum. It’s a film forum.

Bravo, Dr. Film. Context is everything and that should be addressed. “Song of the South” was based on the tales of Joel Chandler Harris. I saw the film as a child and I do not think anyone believes I’m racist.

The issues you raise call to mind the recent furor over the current president of Purdue University, our ex-governor Mitch Daniels, wanting to ban the books of historian Howard Zinn in our schools. No! Whether or not one agrees with Dr. Zinn’s interpretations of history (and history is, in fact, interpretation), his views should be allowed to be read.

In the case of Song of the South I have more problems with the book. The Brer Rabbit parts are fine (though the dialect writing is antiquated and a bit offensive in its own right) but the bridging sequences with Uncle Remus and the little boy are patronizing at best- the Disney film manages to make them easier to take.

Great article. Another case of the absolute silliness of trying to ban something because it’s “offensive”, of more recent vintage, was the uproar a couple of years back over the racist content of Huckleberry Finn. The silliest part, to me, was that many of the folks who were all for banning this Mark Twain classic are the same one who defend the drivel spewed by the likes of Kanye West and Eminem as “art”.

This is prompting me to go back and look over the Joel Chandler Harris stories again. Now _he’s_ a controversial figure, but in a relatively subdued academic way; his writing the Uncle Remus stories are seen as cultural and dialect anthropology as well as racial suppression, but it gets more complicated the more you investigate him and his writings. Nobody screams about Harris the way they do about SONG OF THE SOUTH. (I’m half tempted to write that last sentence in dialect – but I can’t choose one to employ; the very word “dialect” seems to offend now. How about Finnish with an overlay of South Bronx?)

Interestingly, I HAVE read some of the Harris stories, and they’re variable in their racist content. They are also well-beloved in the South, something that we Yankees often forget. They’re not beloved for their racism, but for the way they codify so many aspects of Southern culture.

I’m glad you’ve read some of the stories, Herr Doktor. As I recall, Harris was something of a progressive in his time. He certainly had the reputation of possessing an inquiring mind and a humane outlook, two things not often encountered in post-Reconstruction Southern cross-race writing. As I said, his legacy and standing are complicated. I really need to read his stuff again and get a fresh view.

I’m not a film person, but as a historian, I’m interested in these items as cultural artifacts. As offensive as they are, they’re an important part of understanding a period in time. “Banning” these films denies us the possibility of observing that facet of people’s opinions. Some of choices for banning also seem to be subjective. I consider “Gone with the Wind” to be a racist film, but no one seems to want to ban that. Some studios have attempted to deal with this by editing the racist parts out, (i.e., some of the Stepin Fetchit films), but that changes the meaning of the cultural artifact and also goes from demeaning a group of people to simply denying that they exist. I had a thought on how films like this might be dealt with. If a film student wants to see “Birth of a Nation” – or for that matter, “Triumph of the Will” – they may do so because these films are in the public domain. No one profits from showing the film and it can be judged on its own merits or demerits. Releasing a film into the public domain would be an acknowledgment by the present owner of a film that the material in it is no longer considered appropriate and would relieve them of the responsibility for the opinions expressed in the film. (However, if someone wants to continue to profit from racism, then perhaps it’s time to discuss reparations.) A blue-ribbon committee of film scholars and African American history scholars could certainly come up with a list of films that could be rated RPD – “Racial Public Domain”. It is important that we as a society not attempt to ignore or destroy parts of our history that are an embarrassment to the present culture. It’s part of learning what influences were a part of creating the society that we are today. The Disney Corporation could make an important step in this direction by acknowledging their past and releasing “Song of the South” into the public domain to let the public decide on its intrinsic worth.

It’s a great idea. Let’s see how viable it is. Disney has spent millions in bribe money, er campaign contributions, to keep everything it has ever made in copyright, and I don’t see how this one would ever be an exception.

Couplea things…. First, nothing in the Bill of Rights is absolute. And absolutist view of the 2nd Amendment prohibits laws against selling machine guns to 5 year olds. An absolutist view of the 1st Amendment prohibits laws against sexually exploiting that 5 year old in the film that the one justice didn’t need to see. The 1st and 4th Amendments are in active opposition to each other; an absolutist view eliminates the very need FOR a Supreme Court.

Second, I completely agree with you re racist images in old media. I encounter young people regularly who honestly believe that black people are just “too sensitive” when it comes to claims of racism in media. We encourage that belief when we scrub media history clean of its racist past. When I get asked “Why are black people so sensitive about that stuff?” I always reach for a UK paperback from the 1960s of Agatha Christie’s 1930s mystery which now goes by the name “And Then There Were None.” The original title was “Ten Little Niggers.” It’s not a KKK pamphlet, it’s the single most successful mystery novel ever written by anybody ever.

While I think it would be a mistake to just air the racist WB cartoons of the 30s-40s on Saturday mornings as regular programming, it would be a huge tragedy – and far greater mistake – to erase these from our cultural history. If there is an actual undeniably true thing it may well be that “those who forget history are condemned to repeat it.”

Of course the First Amendment isn’t absolute. And in the play, it’s not a 5-year-old being exploited, either.

Your example of the Christie novel is well-taken. It’s racist, and really awful. Shouldn’t be denied. That said, it’s a great mystery novel too. It’s worthwhile art AND it’s racist. We can’t separate the two.

As a person who has been banned himself from certain newsgroups because of his opinions (and oddly enough, like NOSFERATU, is doing just fine thanks) and as someone who once opened a commentary track for the Minstrel Show movie YES SIR MR. BONES (1951) with the words “If you are offended by this sort of material………..why are you watching it?”, I can personally vouch for the silliness of the attempted banning of anything from the public consiousness. If one wishes to see SONG OF THE SOUTH, one has to go no farther than Youtube, where it remains perenially and Disney seems to turn a blind eye unlike most of its other materials which turns up on that channel.

Yet we live in a world (especially on the Internet) where we can insulate ourselves from any disagreeable information, we can create our safe little Facebook havens where we see only our friends and can “unfriend” anyone who might have something to say that we don’t want to hear. We get our news only from the websites and newsgroups who say what we think we believe in, so we don’t ever have to have our fragile beliefs challenged. We can sit in our virtual worlds, feeling that false sense of security, and convince ourselves that we are right and good.

In banning something like SONG OF THE SOUTH, just who are we protecting, the African-Americans? They know just how racist this Country has been and still is, seeing that film is not likely to offend them or tell them something they do not already know. We are only protecting we right and good white-folk, so we can try to convince ourselves that we are still and always have been right and good and would have never, ever, done anything nasty to anyone else, and that delusion is always the most sad and dangerous of them all.

RICHARD M ROBERTS