Do you recognize this woman? She was a fashion editor for Harper’s Bazaar, a famous singer at the Metropolitan Opera, and she had her jaw broken by Barbara Stanwyck.

Do you recognize this woman? She was a fashion editor for Harper’s Bazaar, a famous singer at the Metropolitan Opera, and she had her jaw broken by Barbara Stanwyck.

And yet you probably don’t know her for any of those things.

The woman in this photo is Kathleen Howard (1884-1956), who is best remembered today as probably the most memorable in a string of “shrewish wives” depicted in WC Fields films. Like Fields regular Elise Cavanna, who I wrote about last year, Howard moved seamlessly between major careers. She was renowned in each one, but each was different enough that many people don’t realize that she was the same Kathleen Howard.

Howard’s performances in three of Fields’ films, You’re Telling Me (1934), It’s a Gift (1934), and The Man on the Flying Trapeze (1935) are nothing short of brilliant. It’s easy to descend into just a bitchy, clichéd performance as a Fields wife, but Howard transcends that. She’s given the characters a back story, and you can feel the frustrations in her life that have made her into the person she is. That said, she is also supremely awful to Fields, in ways that have him cringing in fear. Howard is human but still horrible.

Howard’s performances in three of Fields’ films, You’re Telling Me (1934), It’s a Gift (1934), and The Man on the Flying Trapeze (1935) are nothing short of brilliant. It’s easy to descend into just a bitchy, clichéd performance as a Fields wife, but Howard transcends that. She’s given the characters a back story, and you can feel the frustrations in her life that have made her into the person she is. That said, she is also supremely awful to Fields, in ways that have him cringing in fear. Howard is human but still horrible.

Back in the pre-internet days, we’d look at Howard’s filmography and see that she seemed to burst on the scene in 1934 with a supporting performance in Death Takes a Holiday. But where was she before that? Most stage actors dabbled in silent film and had a few credits before gaining fame in talkies.

But Kathleen Howard never made a silent film. She was busy singing. As a child, she wanted to be a singer, but everyone told her that could never happen. That didn’t stop her. She worked her way to the top as a contralto at the Metropolitan Opera.

She even wrote a highly entertaining book about it. It’s called Confessions of an Opera Singer, and you can read it here. Interestingly, her story parallels Edie Adams’ story (which Adams also chronicled in a book). Both were told that they couldn’t make it as singers, that almost no one really did, that women couldn’t handle their own careers, etc. And both were determined to make it anyway, which they did.

Howard was popular enough outside the opera house to be a recording star, and it’s actually fairly easy to hear her singing in the late teens and early twenties. Here are some.

But the best parts are for young singers, and Howard got a little old for it by the mid-1920s, so she switched gears. She became the fashion editor for the magazine Harper’s Bazaar. This was no third-rate magazine; it was one of the best in the business, and Howard wrote many articles while managing the other contributors. (This also parallels Edie Adams somewhat, since Edie became her own fashion designer in the 1960s.) You can see the cover of one of her Harper’s issues here.

Then, abruptly, in 1934, she offered her talents to Hollywood. This may sound like a leap of faith, but as an opera performer, one is also doing a great deal of acting, so she was not without considerable experience.

Again, I don’t like to link to YouTube clips that violate copyright, and I didn’t post this one, but in this case, I really think you need to see Howard in action. This is the porch scene from It’s a Gift (1934), which is one of the funniest scenes in one of the funniest films ever made. If you don’t agree with me, then you’re wrong. I’m not even going to argue with you about it.

People like Howard fascinate me because they’ve had successful careers in varied fields. I tend to be unsuccessful at everything I attempt, and yet Kathleen Howard was at the top three different times. I love her blend of careers and the way she just seemed to move effortlessly among them. Sometimes performers are inactive for years at a stretch while they regroup and try something different. Not Howard. She was in there and working.

Howard was just another of the brilliant people who surrounded WC Fields. Contrary to his public image, I am more and more seeing Fields a loyal friend who helped out other actors. Howard and Elise Cavanna were both great performers who did multiple roles.

Another guy I keep spotting in Fields pictures, sometimes just in the briefest walk-on part, is Lew Kelly. I’d love to have a whole write-up on him, but I just don’t have enough information, so I’ll hijack this posting a little for him.

Kelly (1879-1944) was a vaudeville headliner who traveled the world as Professor Dope, a character that apparently made fun of drug addicts (this was very popular in the teens.) By the 1920s, his career had more or less dried up, but he became a popular utility player for many comedians in the 1930s.

Kelly appeared with Wheeler and Woolsey, multiple shorts with the Three Stooges, but he’s in seven films with WC Fields from 1932-35, often in uncredited bit parts. Kelly was one of those guys who could just be pointed into the scene and would give a good performance every time.

What does all this add up to? Not much, I suppose. It gives a little context to history. I see some of these films and wonder who some of those people were in their “real” life. I keep finding that the answers are really fascinating to me, and I hope they are to some of you, too.

FOLLOWUP:

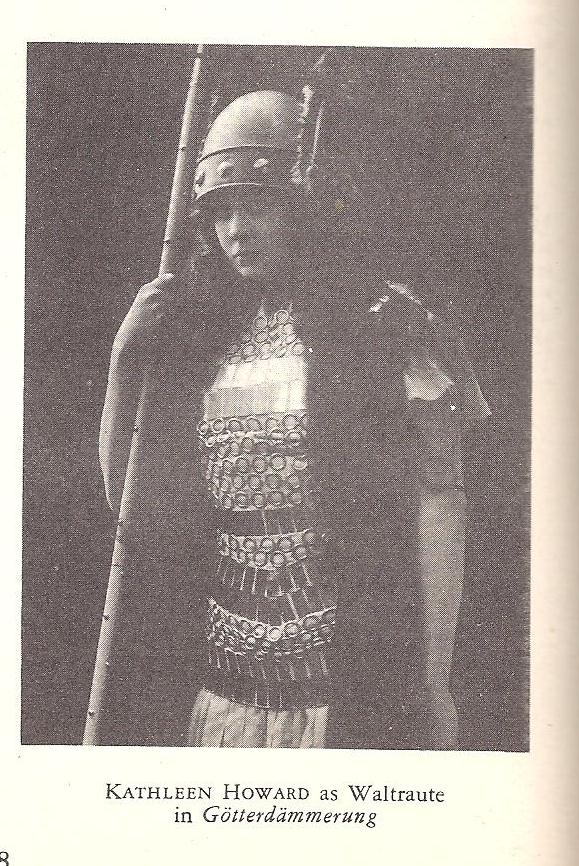

I had some fascinating off-line chatter on this topic. Dr. Philip Carli sent a nice followup in a response that I’ll include in the text here. Also, David Heighway discovered a nice picture of Howard in Götterdämmerung that I just had to post. Here are both of these followups.

Carli:

It should be mentioned that Howard was the leading contralto at the Metropolitan Opera in the teens alongside the legendary Ernestine Schumann-Heink; both women were among the very few of their period to achieve popular celebrity in that voice, and indeed both singers had extremely wide ranges, reaching well up into the mezzo-soprano range as well as into the low alto register. Judging from her few Pathé and Edison recordings, she was one of the great ones, but her career was awkwardly placed on each side of WWI so her career was largely split between Germany and the US. Although contralto parts are often secondary and frequently “women of a certain age” parts, Howard’s vocal and acting range was wide enough that she sang the title roles in Saint-Saens’ Samson et Delilah and Bizet’s Carmen with great success in Europe, and she looked pretty sexy in both parts, judging from contemporary photographs. She also created at least one notable operatic role, that of the greedy and pompous aunt, Zita (originally named “La Vecchia”, or “the old lady”), in Puccini’s only outright comedy, the one-act Gianni Schicci, which had its world premiere at the Met on 14 December 1918 with the celebrated baritone Giuseppe de Luca in the title part and American soprano Florence Easton as Lauretta (who sings “O mio babbino caro”, one of Puccini’s most famous arias); music critic James Huneker praised Howard’s comic performance as “the horrid hag” in his New York Times review the next day, unwittingly predicting the way her acting career would go with Fields.

Heighway’s photo: