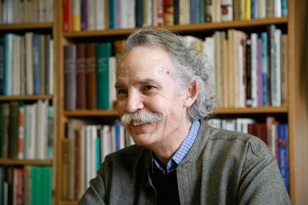

Sometimes, when I least expect it, I hear a nugget of wisdom that just keeps me thinking for days. On March 28, I attended a lecture at Indiana Landmarks about historic buildings. This will be of no surprise to the folks who know that Indiana Landmarks promotes (among other things) preservation of historic buildings. The lecturer was Henry Glassie, a really top-notch guy who gave a smoother lecture than I ever could. (Full disclosure: Indiana Landmarks is also hosting a showing of my restoration of The King of the Kongo in July of this year, but I’m not shilling for anyone.)

Glassie spoke about surveying historic buildings in Virginia, and he had traced the designs to countries that had had similar designs in Europe. Barns and houses, primarily. He noticed that there was a definite pattern in the buildings depending on where the inhabitants had originated in Europe. He also noted that the folks in the American South had cleverly adapted some of these buildings to make newer and more useful designs, while retaining the original character of the older design.

Then he started speaking about what happened to these buildings over time. You may know that a lot of barns are endangered today simply because we don’t know what to do with barns, since farming is now industrial and not familial. And modest old houses are a bit of a problem as we move into larger McMansions to hold all of our stuff. Glassie noted that all of the houses he had surveyed… all of them… that represented what is perceived as the popular cultural history of Virginia, had been saved, and in many cases restored. The others—the little dwellings, the sheds, the outbuildings—were either gone or in worse shape than ever.

The plantation houses, the houses of the rich, the story of Gone With the Wind and all that goes with it… those were saved. The smaller houses, the ones for poor families, the odd barns, the work buildings… those were being demolished, because no one wanted to deal with them.

“It’s important to save some of these,” Glassie said, “because these buildings tell us of the history not found in books.”

My mind spun! I loved this idea. I knew exactly what he meant. We preserve the popular stuff, the stuff we know about, the stuff we can still identify with, and the rest gets swept under the carpet. It doesn’t fit in with our idea of the past, so out it goes. Who cares if it documents a truth that a clever historian can read and decode? It doesn’t fit our narrative, so begone!

And immediately, I realized that this is the kind of film history I practice. The film history not found in books. I realized that this is why the “Holy Quintet” of classic films annoys me a little (Casablanca, The Wizard of Oz, Gone With the Wind, Citizen Kane, and Singing in the Rain.) Those stories have been told. They’ve been retold. They’re part of our narrative of film history.

This is why, in popular culture, Gone With the Wind is the first Technicolor film ever made. Who cares that Becky Sharp came four years earlier? And what of the two-color Technicolor that dated back to 1917? It may be true, but it doesn’t fit our narrative—out it goes.

The trouble with this is that what doesn’t fit the narrative doesn’t get seen, and what doesn’t get seen doesn’t get preserved. It’s the same with films and buildings. In the words of Hannibal Lecter, “We covet what we see.” And if we don’t see it, then we don’t care.

OK, it’s a little granule of a thought, I admit, but it’s a powerful one. The history not found in books. Wow. I began to realize that I fight very hard to tell film history not found in books. I find so many fascinating nooks and crannies that I want to share them.

I’m kind of the opposite of the traditional film history guy: If the story has been told, then I want to move on to a new story. Yeah, I know about the script troubles in Casablanca or Buddy Ebsen in The Wizard of Oz. What else is there?

I remember when I first started showing the pilot for Dr. Film. People screamed at me. “OK, we like what you did with the characters, we like how you did the show, but the feature you picked, Murder by Television (1935) is terrible! You should take that out and put something good in, something like White Zombie (1932). That’s about the same length and it’s at least a decent movie. And since it stars Lugosi, you’ll only have to re-shoot the ending, so it’ll save the whole show.”

But I didn’t want to do that. I refused to do that. I have a very solid concept for Dr. Film and White Zombie wasn’t it.

I like White Zombie. It’s a fine film. Lugosi is great in it. It would make a fantastic episode of Matinee at the Bijou. And, for the record, I like Matinee at the Bijou. But Dr. Film isn’t Matinee at the Bijou. It’s seeking to tell the untold stories.

In the opening credits, the members of the Midnight Film Society slink into their chairs and the narrator solemnly intones, “…they screen the unseen…”

White Zombie isn’t unseen. It’s one of the most common Lugosi films out there. If you’ve seen 15 Lugosi films, you’ve seen White Zombie. Since I don’t have a fantastic rediscovered print like Tom Holland found, I didn’t have anything unique to show.

As this little nugget of truth continued to worm its way into my skull, I came to realize just how much I love the untold stories in film history…

I lobbied last year (and this year) to restore The King of the Kongo because it represents so many untold stories: What was Boris Karloff doing in movies before he was famous? What were the early sound serials like? Did early part-talkies use undercranking? It isn’t a great movie either, but it deserved to be restored. It needed to tell its story.

Max Lerner once said, “History is written by the survivors.” Film history is too. I love DW Griffith, but is he really the father of film? We’ve found out recently that other people at the same time were doing innovative work as well. Griffith had the advantage of being preserved and available because of MOMA and Library of Congress, but it’s only recently that we could see early works by Raoul Walsh or even Cecil B. DeMille (whose early work is really cool… before he started making stale costume dramas that made more money.)

We know Fritz Lang (survivor) but not Paul Wegener (most films lost).

We know Willis O’Brien (survivor) but not Charley Bowers (many films lost).

We know Laurel and Hardy (only one short lost) but not Max Davidson (fewer shorts, and several missing).

The stories of Cecil B. DeMille and John Ford are changing as we find their early work to be more interesting and significant than we had thought.

MGM star Clark Gable we remember, but what of MGM star Lee Tracy? There was a time when Tracy was a much bigger star.

I find myself drawn to these kinds of things. I find that the films in the popular culture, the ones written about in books, are often no better than the obscure little pictures we’ve never seen.

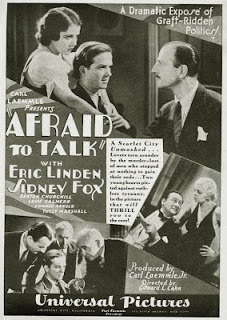

A couple of years ago, Universal reprinted Merry Go Round (1932), which might as well have been a 1945 film noir. Universal had a stupid policy in the 1960s and 70s: if it wasn’t a monster movie, or it didn’t have Bob Hope, Abbott and Costello, WC Fields, or the Marx Brothers in it, then it wasn’t worth reprinting. This meant that scads of great titles from Universal and Paramount (Universal owns the Paramount library from 1929-47) are sitting unseen in vaults because they were deemed unmarketable.

Merry Go Round was a great story of double dealing, corrupt city officials, shady lawyers, bed-hopping, etc. Just the kind of thing that would be great cinema in 10 or 15 years. And we’d never heard of it.

Because we’d never seen it.

Because its story wasn’t told in books. (And there was no reason to tell its story in books, since no one had seen it. Sitting there in a film catalog, it doesn’t look particularly interesting.)

OK, maybe I screwed up in showing Murder by Television on Dr. Film. I personally find this an “are you kidding me?” moment in Lugosi’s career. He’d just done The Raven at Universal, and now this? Why? And you unravel the answer: he needed cash, so he would take work anywhere.

Sure, it’s a bad film. But why it’s a bad film is really fascinating. And I find it a fascinating film to see for its badness. That doesn’t mean I only want to show bad films.

And it certainly doesn’t mean I want only to show good films.

It does mean I have no interest in showing Casablanca, Gone With the Wind, The Wizard of Oz, Singing in the Rain, and Citizen Kane. Come to think of it, lump White Zombie in with them.

I’m still fascinated with film history–obscure but interesting and worth revisiting—the history not found in books. If Dr. Film ever makes it to air, then you can expect to see more of these kinds of stories. I’m happy to leave the mainstream to Robert Osborne. He’s better at that than I am!