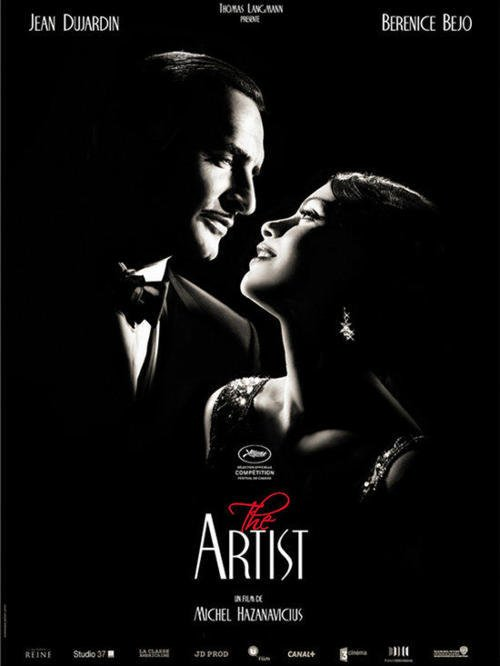

Now that The Artist has won the Best Picture Oscar, I’ve been asked by numerous people to recommend other silent films. People treat me as if I speak a foreign language and that perhaps I can teach them the secret to unlocking it. In a way, this is really true, because silent film uses a different filmic syntax, and it’s one that has to be learned with repeated viewings. Silent film technique is not primitive… it is quite advanced, in fact, but it is fundamentally different from the techniques we use today. That’s why it can seem a little silly if you are not used to it.

Most of the people who ask me about silent films are younger folks who are just discovering silents. I hope this will dispel the myth that I somehow dislike younger people or “newbies,” which is definitely not the case. The entire goal of the Dr. Film show is to be able to include films and shorts that will appeal to a broad audience, from newbies to dyed-in-the-wool film geeks.

What I don’t like, and will continue not to like, is the persistent cultural idea that there were only five films made before Star Wars, which seems to be the oldest film most people will watch. I refer to these as the “Holy Quintet” of classic films. (See the end of this article for the list of the “Holy Quintet,” just in case you’re wondering.)

Silent films suffer even more in popular culture, They were often copied poorly, causing them to have that blown-out over-white look, and they were often transferred at speeds that were completely incorrect. This only hurts the whole of silent film, because originally all the prints were lovely and they were all projected at reasonable speeds.

Most articles that I see trot out the same few silent films, often with a dismissive swish that these are flickery and sped-up, not understanding the basic idea of what silents were about.

If you’ve been reading about The Artist, then you’ve seen these articles, too. Everyone wants you to see Sunrise, Passion of Joan of Arc, City Lights, Metropolis, and Intolerance. These are becoming the clichéd “see these after you’ve seen The Artist” list.

The problem that I have with this list is that they are not terribly accessible. Not in a strict sense of availability–these films can all be found on video, and often downloaded. The problem is that these are not films I’d recommend for newbies. It’s the equivalent of handing Beowulf to a kid who’s just finished Green Eggs and Ham. Sure, Beowulf is great, but the poor kid is probably going to be put off a lot of literature because this is just too much for him.

All of the films in the “see these after you’ve seen The Artist” list are films I’ve seen, and one of the things that they share is that they tend to be rather broad-sweeping epics. They tackle big issues, they’re big and ponderous, and they’re “arty.” There’s nothing wrong with that–I like these pictures–but I fear that the won’t play well for viewers who are new to the medium. Worse still, these are all films that demand a great deal of concentration and play infinitely better on a large screen with an audience. I’ve got to face the fact that I need to hook new viewers by finding films that will play well on an iPhone. Then I slowly must convince them that the theatrical experience is far superior especially for silents!

I need to emphasize once again that silents are fundamentally different from talkies. You can watch Transformers 3 and walk into the kitchen, come back, and you’ve heard all the explosions and dialogue that you need to follow the story. We can’t do that with silents. If you miss two or three minutes, then you may be lost. More importantly, there are things we can do in talkies that we can’t do in silents, but there are things that we can do in silents that we can’t do in talkies.

Ben Model frequently points out (and accurately), that one of the things we can do in silents is to have large, noisy objects sneak up behind the protagonist while he is unaware of them. In Buster Keaton pictures, this is often a train. When Buster’s back is to the train, even if we can see it, we’re somehow able to believe that Buster can’t hear it. We don’t hear it either. Once he sees it, then he is aware of its existence. Sight is the only sense we have in a silent film.

The other thing that many have already gleaned from me is that I tend to veer off the mainstream, so I figure that you can find all the big, epic silents you need. I’ve prepared a list of ten silent films that I hope will encourage you to see more.

These are not what I think are the ten best silent films. I hate lists like that. These are not my favorite silent films. I hate lists like that. These are not even what I consider a balanced overview of what silent films represented. I’m not sure I could do that with just ten.

Here are the criteria I used–

- The film must be available in some way on video or for download.

- The film should be something that helps showcase the uniqueness of silent film. It should either be something difficult to make as a talkie or something that was never attempted again for other reasons.

- Big photographic epics that play well on big screens should be avoided. Tight comedies or dramas play better on small screens.

- Let’s have some fun and pick films that most others skip over and don’t mention.

The list, in random order, not by quality.

- Sherlock Junior (1924) with Buster Keaton. I didn’t want to pick The General, because everyone will pick it, and because it’s a little too epic for new viewers. Still, Keaton has a special timeless quality about him that appeals across generations. This film is action-packed, and it contains a delightful sequence in which Keaton walks into a movie screen. Again, it couldn’t be made as a talkie, because the “film” he walks into is bizarrely disjointed and would contain wildly disparate sounds to destroy the illusion. Sherlock is probably not Keaton’s best film, but it is a film I think would appeal to a broad audience.

- The Mark of Zorro (1920). I have to include a Douglas Fairbanks title in this list in order not to feel inordinately guilty. Thief of Baghdad needs to be seen on a big screen, but Zorro is a blast no matter how you see it. I’m not going to recount the Zorro legend to you, because you should already know it. Fairbanks plays him brilliantly. He was a force of nature, an unstoppable guy who seemed to embody the term “irrational exuberance.” Fairbanks was not afraid to break all the rules of filmmaking and storytelling, either. The last 20 minutes of so of Zorro is a non-stop chase. It’s too long, it stops the film cold in its tracks, and it does nothing to forward the story at all. I loved every second of it and would never cut a single frame. Fairbanks makes it work.

- Films of Max Davidson. Available only as a German DVD, mostly due to rights issues and because Americans don’t like the idea of Max in general, these films are gems. Max had his own series of short films under producer Hal Roach in the late 1920s. He could hardly have misfired with the help he had available: many of the shorts were directed by young comedy genius Leo McCarey and photographed by budding genius director George Stevens. Still, Max is one of the great comic performers, if only because he reactsso well. Max’s reaction shots are a model of how a comic can and should stretch a funny situation for maximum laughs.One example I can give of Max’s brilliance is in Pass the Gravy (1928). This is truly one of the funniest short films ever made by anyone at any time. And it basically has one jokestretched out for almost 20 minutes. I can even tell you the joke without giving anything away! Max’s character is a stereotypical little Jewish guy from the 1920s, complete with beard, cheapness, etc. He generally has an idiot son who commits some sort of mischief. In this one, the son accidentally kills the neighbor’s prize rooster, Brigham. The son then cooks it, leaving the FIRST PRIZE band highly visible on the rooster’s leg. The family serves it up to the neighbor in hopes to mend the discord between the two families. Max doesn’t understand what’s happened, but the rest of the family does, and they desperately try to explain the problem in pantomime so that the neighbor doesn’t find out. It’s a work of genius.Should Second Husbands Come First? manages to top this in terms of sheer political incorrectness. Money-grubbing Max is trying to marry a rich widow, much to the dismay of her two sons. They concoct a scheme to break up the wedding: one son dresses up as a shamed woman, holding a young child “she” claims to be Max’s illegitimate son. The boys could only find a black baby for their shenanigans, so they powdered all the visible parts. Mortified at the events, Max’s cheap friends quickly take back all their wedding gifts. The baby’s pants fall off, revealing a posterior of the incorrect tone. The ruse is exposed, and Max demands all the presents be returned. Yes, folks, in the space of 45 seconds we have two Jewish jokes, a black joke, and a butt joke.Hal Roach felt these were all OK because they were not of a vicious nature and everyone was subject to the humor in these films. I tend to think he was right, but there are still people who think these films should be banned. Maybe they should be banned, but you should see them first, because they are truly hilarious.

- Grass and Chang. These two groundbreaking documentaries are about as fascinating as movies get. I don’t want to tell you too much about them, because they have to be seen to be believed. The thing to bear in mind while seeing them is that they were made by Merian C. Cooper and Ernest B. Schoedsack, who later made King Kong (1933). You start to realize in watching these films just how much Cooper borrowed from his real-life experiences when making Kong, and you see a glimpse of native life (and wildlife) in Asia that was not captured any other way. There are probably more tigers killed in Chang than exist worldwide today! Beautiful photography, intense editing, fascinating action sequences. Yes, they’re violent, not for young children. Yes, they’re hoked up for maximum effect. That doesn’t stop them from being landmark films. As a side note, it’s important to realize that Cooper was basically the real-life (and smart) equivalent of Forrest Gump. Almost every major event in the 20th Century had Cooper’s involvement: he was a WWI aviator, POW, anti-Communist, pioneer in the aviation industry, documentary filmmaker, studio head, major investor in Technicolor, major backer of David Selznick and John Ford, WWII hero, major investor in Cinerama, and several other things. Amazing films, amazing man.

- The films of Charley Bowers. I don’t know what to say about this guy. He’s unique in all of cinema. Was he smoking something? Probably. Bowers’ blend of stop-motion and live-action was pioneering and mind-blowing. Sadly, most of his films were lost for many years, and many have only been rediscovered in the last decade or so. Bowers’ comic character was sort of a combination of Chaplin and Keaton with a bizarre inventive streak thrown in. Bowers casually showed elephants walking into the Capitol in Washington DC, with effects as convincing as any today. In one film he invented a solution that could graft anything onto living plants. A desperate farmer, overrun with vicious mice (bearing machine guns), hired Bowers to eradicate the pests. Bowers solved the problem by harvesting cat-tails, grafting them onto plants, at which point live cats sprout from the plants! This is all shown on screen in full view. Bowers’ stop-motion happened simultaneously with Willis O’Brien’s work. While Bowers never animates dinosaurs, he meshes live action with stop motion in brilliant ways that O’Brien never tried. O’Brien and Ray Harryhausen rarely moved their camera during animation, but Bowers gleefully pulls back from a closeup to longshot, effectively animating both camera and model. Bowers is one of the great rediscoveries of the past twenty years, the kind of rediscovery that keeps collectors like me digging for more lost films.

- The Wind (1928) with Lillian Gish. Swedish director Victor Seastrom (aka Sjöstrom) was a great innovator in silent cinema who returned to his native land and eventually acted in Bergman films. This one is one of his best and most effective. Again, it’s simple. Gish is an innocent young woman stuck in a small shack in the desert. She’s been stuck with crass, unfeeling relatives in a hot, desolate landscape. Her isolation is something we can feel intensely, and we can understand her starting to go slightly mad in the environment. In self-defense, she kills a man who was making improper advances, then buries him. A wild windstorm ensues, blowing up the dry sand all around the shack. The man is uncovered and flails around outside at the windows. Is he really dead? Gish has to deal with a range of emotions and a terrifying situation. It’s a brilliant film, not screened enough.

- The Unknown (1927) with Lon Chaney. This is a film that doesn’t lend itself to description. I love running it for audiences, because it starts off a bit silly, drawing titters, and then moves into territory that has people cringing by the last reel. Director Tod Browning has been roundly trashed in popular criticism in the last decade or so. Well, whether like Dracula or not, this is a great film. Chaney plays an armless circus performer who throws knives with his feet, at lovely young Joan Crawford. Unbeknownst to almost everyone, Chaney actually has arms, using them to steal and murder after hours. Alas, Crawford sees his form, identifying his unusual double thumb, as he commits a murder. Chaney has a brilliant idea: he bribes a doctor to remove his arms, thereby making certain that he can never be identified for his crime. Chaney’s performance in some of the later scenes is remarkable.

- The Kid (1921) with Charlie Chaplin. I have to include a Chaplin film, and everyone is going to tell you to see City Lights or The Gold Rush. Those may be more important films, but The Kid is very accessible, very well acted, and filmically very important: it was the first major comedy feature picture. Certainly, Tillie’s Punctured Romance (1914) is also a feature (just squeaking by the time requirement), but The Kid is far more advanced structurally. It paved the way for comedies and comedy-dramas for years to come. Jackie Coogan is a wonderful child performer, and Chaplin exploits him perfectly. Chaplin’s mastery of both film direction and geography meshed with his sensitive portrayal combines to make this a great film.

- The Patsy (1928). Marion Davies is one of the most maligned talents in cinema. Citizen Kane unfairly portrayed her as a talentless hack, something that Orson Welles regretted in interviews for years. Her long-time lover, William Randolph Hearst, often threw Davies in costume dramas, a genre for which she was ill-suited. When left to her own devices, Davies was an ace comedienne, able to make a charming performance from even the frothiest script. In this film, as the forgotten “good girl” in the family, Davies loses all the cute men to her sister. Thinking she needs a better personality, Davies impersonates Pola Negri, Lillian Gish, and Mae Murray. (Don’t worry, it’s funny even if you don’t know the people she’s imitating). Davies is a delight to watch in her attempts to win the favor of a young man– a man also being pursued by her sister. Throw in sterling work by Marie Dressler as the mother, and this is a howl from start to finish.

- Destiny (1921). I know the pundits are going to say Murnau, Murnau, Murnau! To you I say, Lang, Lang, Lang! Murnau is more pretentious and arty than Lang, and Lang, (when he’s not being long-winded and preachy), is more accessible. This, to me, is his best film. A young woman, Lil Dagover (also the female lead in Cabinet of Dr. Caligari) is distressed when her lover leaves with a stranger and does not return. The stranger is Death, and his garden wall is impenetrable. Eventually, Death agrees to a challenge: if she can defeat him and save just one of three men from his fate, then Death will reunite the lovers. This concept has been ripped off a zillion times, from The Seventh Seal to Bill and Ted’s Bogus Journey. Sadly, the surviving prints of this film aren’t the greatest, so I’m a little hesitant to recommend it on that level, but I hope viewers will find its simple story so compelling that it overcomes the deterioration of poor copying.

I know that I’m going to get brickbats hurled at me because of these choices. What? No Harold Lloyd? No DW Griffith? No deMille? No Arbuckle? No Ince? No William Desmond Taylor? No Louise Brooks? No Colleen Moore? No Valentino? No Napoleon?

Well, this is the problem with lists. You note that I produced more than ten examples of people omitted from this silly list. I hope that these films will pique your interest and challenge you to watch more silent films. I hope it will encourage you to patronize some of the revival theaters and film conventions that trot out many rare films that can only be seen on the big screen.

(And OK, you made it this far. The holy quintet of classic films are as follows: Casablanca, Citizen Kane, The Wizard of Oz, Singin’ in the Rain, and Gone With the Wind. I actually had a theater manager tell me that he’d just like to have a theater running a different one of those five films every week because they’d all do good business. So much for challenging your audience a little!)