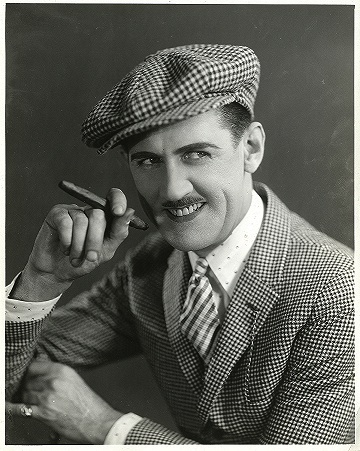

I’ve known Mike Schlesinger for a number of years. Just how many, I’m not sure. I ran into him at a film convention some time in the late 1980s or early 1990s, and laughed at one of his T-shirts. Despite what he says, he has a collection of odd shirts, always film-related, most I’ve never seen anywhere else. We also share a fondness for really stupid jokes and bad puns.

Mike is very modest and soft-pedals his various accomplishments. I can tell you, and without hyperbole, that for years he was the only guy in distribution at any of the studios with a clue about movies made before 1950. Today, the vast majority of them still don’t have a clue, and many actively don’t care. (There are more people who care now than when I started, but we can still use more.)

With most studios, it was, “Do we own that? Is that ours?” The really inept ones would tell me that they didn’t own the film when I knew they did. It was too much work to look it up. Mike would immediately know if a print was on hand, and if the film had changed hands, and he always knew who to call to help me book an odd print.

And while Mike may also downplay his contributions to film preservation (I deeply admire all the guys he mentions), he has done a lot behind the scenes to make things happen. When he was at Paramount, old Paramount titles got reprinted, and when he was at Sony, old Columbia titles got reprinted. As I always say, access is half the battle for preservation, and Mike was great about making sure prints were out there and could be rented.

Mike’s trailer for Lost Skeleton of Cadavra

Q1. You have a long history with film preservation and working at the studios. Tell us a little about each place you’ve worked and some of the things you’ve done. Are you really Leonard Maltin’s favorite film executive? Does Leonard really exist, or is he a figment of my imagination?

Actually, I’ve never preserved a foot of film in my life. Others, such as Dick May, Grover Crisp and Barry Allen, oversaw all that work. My job was in distribution. I have indeed made suggestions of specific titles, but again, I never had my hands on film. Think of them as the chefs and me as the waiter. I worked at MGM/UA, Paramount and until last December, Sony (Columbia). Each was a unique and largely satisfying experience, though ultimately I’d always run afoul of people above me who didn’t understand what I did and why it was important. Among my most fulfilling experiences (aside from the ones discussed below): bringing out the “director’s cuts” of The Boy Friend, Wild Rovers, 1900, The Conformist, Wattstax, Darling Lili and getting the ball rolling on Pat Garrett and Billy the Kid; prying The Manchurian Candidate, Broadway Bill and White Dog out of movie jail; the record-breaking 50th anniversary reissue of Citizen Kane, and the extended version of Major Dundee. Striking new 35mm prints of numerous Columbia cartoons and shorts was also a treat. (Plus I made a number of trailers which, if I do say so myself, were, as the kids say, pretty freakin’ awesome.)

It was Roger Ebert who said I was his favorite Hollywood executive. Funny story: When that hit print, I e-mailed him, “Who came in second?” He replied, “What makes you think there was a second?”

Leonard does indeed exist. I’ve even hugged his lovely wife Alice.

Q2. You’re a long-time Godzilla fan. Tell us about your involvement in Godzilla 2000.

Well, that’s not a short story, but I’ll try to make it so. Sony’s distribution chief Jeff Blake (whom I largely owe my career to) happened to be in Japan when G2K opened and was breaking records. Since the Emmerich version didn’t turn out to be the most-beloved film of its generation, the studio was unsure of how to proceed. Jeff felt that releasing G2K here would be at least a place-keeper and at best a make-good to the fans who felt let down by the Emmerich.

We had a screening, and there was considerable concern: the pace was slack and the dubbing was pretty dire. Jeff was having second thoughts. I assured him that with some judicious editing and a new dub it’d be right as rain. He said, “Okay, then you do it.” And just like that it was in my lap. He figured, I hope correctly, that I was the only one there who’d actually seen some Godzilla movies and would have the right handle on it. So with a release date breathing down our necks, I dove right in.

Jimmy Honore, then Sony’s post-production czar, provided me with an editor and a sound man. Toho’s local guy, Masaharu Ina, was also involved, as every single change had to be approved by Tokyo. I wrote a new script, hired a swell bunch of Asian-American actors to reloop, and worked with the editor to sweat nine minutes of fat out of the film (over 130 individual cuts) and restructuring scenes to increase the tension. We rebuilt the soundtrack from scratch, adding some new music cues (including a couple of classic Ifukube themes) and creating foley for scenes that had been played in total background silence. I even did directional dialogue in some scenes. The sound guys were brilliant and completely supportive, and very complimentary whenever I came up with a suggestion that worked. Happily, Toho (albeit a bit grudgingly at first) admitted that our version was a big improvement; so much so that they even re-released it subtitled in Tokyo, as well as a few other countries, like India. The reviews here were mostly positive (if sometimes patronizing). It made money. And best of all, I got a six-week crash course in post-production that has served me very well. Even I was surprised at how quickly I picked it up. And I have the unique honor of being the first person to put a line of Yiddish in a Godzilla movie.

Q3. Wasn’t It’s All True one of your pet projects?

Q3. Wasn’t It’s All True one of your pet projects?

THE project, though more for its importance. After the Kane reissue, I was approached by Myron Meisel and Bill Krohn, who had been trying to put the picture together, but Paramount owned the footage. Balenciaga was willing to pay all costs in exchange for distribution in France, Germany and Italy. So it was basically a free movie. I managed to get everyone into the same room, and after 14 needlessly drawn-out months, the deal was done. The film was completed on schedule. We were premiering it in the New York Film Festival–the first Paramount picture with that honor since Nashville. And then the distribution heads, for reasons still unknown, decided to kill it, and me in the process. It won the L.A. Film Critics Award for Best Documentary, and no one from the studio came to the ceremony. (I went on my own dime.) It’s the most important thing I’ve ever done…and hardly anyone saw it. 🙁

Q4. You picked up Larry Blamire‘s Lost Skeleton of Cadavra at a time when indies were barely being picked up, and it actually got a theatrical release. Few indie filmmakers are so lucky. Let’s hear about your discovery of Blamire and your involvement with his other films.

God, at this rate there’ll be no need to write my autobiography! Cadavra was a happy accident. The American Cinematheque used to showcase independent films on Thursday nights; I read the synopsis in the paper, it sounded fun, and as I had nothing better to do that night, I went. The theatre was packed: over 500 people laughing their asses off. During the Q&A with the cast and crew, they said it cost “well under” $100,000. I said to myself, “That’s it, I have to have this movie.” I got Larry’s and Miguel’s phone numbers from the Cinematheque, and told them I was interested. As the only other offer they’d received was a lowball from Troma, they were naturally thrilled. Jeff agreed that Sony couldn’t get hurt at such a low price and okayed the acquisition, though there again, it took over a year to get the contract signed. The rest is history, though as Larry himself later acknowledged, getting picked up by a major studio doesn’t guarantee success. It really didn’t find a wider audience until it hit cable. Now it’s the world’s tiniest franchise, and I’ve co-produced Larry’s three subsequent films, with hopefully more to come, including the highly-anticipated conclusion of the first trilogy, The Lost Skeleton Walks Among Us.

Q5. There’s a legend in the film world about your long-lost Godzilla script, which was almost shot by Joe Dante. Please, relate the whole story, down to why it didn’t get made. Is there any hope for it now?

Legend? Seriously? Wow. Anyway, it’s doubtful it’ll ever get made, what with the new Warners version coming out next year. It started, as so much of my life does, with a joke. I ran into my friend Jon Davison one day; he was at Sony producing The Sixth Day. I told him about what Toho was doing with my version of G2K (as related above), and he said, “Yeah, you’re really Mr. Godzilla now.” I laughed, “Yeah, and if these guys were smart, they’d get you, me and Joe to do the next American one.” He said, “Hey, we’re there.” Later in the day, I was pondering this and thought, “Well, why not? Who better to save the franchise?” So I called them both and asked if they were interested. They were, so I went in to the Columbia production head and pitched the idea of a “Wrath of Khan”-like sequel: a modestly-budgeted, man-in-suit picture, using Toho’s effects people, but set in America with English-speaking actors. I said we could do it for $20 million. He was intrigued, but said he really couldn’t authorize it. However, if I wanted to write it on spec, they would certainly consider it if it came out as good as I said it would. That was fine by me.

So I went home and got to work. I set it in Hawaii for various reasons, among them that I’d need no tortured explanation of how Godzilla got there, not to mention the unlikelihood of any actor turning down a feature being shot in Hawaii. (My suggested tagline: “Say aloha to your vacation plans.”) I decided to follow the Abbott & Costello Meet Frankenstein Rule–make the human scenes funny and play the monster stuff straight. I wrote it with genre favorites in mind for the cast: Bruce Campbell, Jamie Lee Curtis, Scott Bakula, Christopher Lee, Leonard Nimoy and of course Joe’s stock company. After jokingly giving it the temporary title of Godzilla—East of Java, I settled on Godzilla Reborn, which referred to not only the franchise but also the storyline, in which he’s killed and eventually resuscitated. Sid Ganis eventually came on board as a producer as well. Everybody adored the script. It shoulda been a no-brainer.

Unfortunately, by the time I finished it, Columbia had a new production head, and he wanted no part of it. Wouldn’t even read it. It takes balls to say that to Sid Ganis, who’s a former Academy president, but he did. And there ya go. Now everyone’s too old for their parts and Warners has the franchise. A damn shame; it would’ve been a monster hit. Pun intended.

Q6. How did your legendary collection of film t-shirts get started? What are some of your most popular?

Huh? I have a bunch of T-shirts, but I’d hardly call it “a legendary collection.” I just buy them like everyone else.

Q7. What the heck is Biffle and Shooster? They weren’t originally your idea, because I found them on YouTube. Who created them and how did you end up with them?

Once again, it started, as so much of my life does, with a joke. Nick Santa Maria and Will Ryan created the team, but they hadn’t really done a great deal with them. Then one day, Nick posted a picture on his Facebook page: the two of them holding up an empty picture frame and mugging. I replied, “From their classic two-reeler It’s a Frame-Up, with Franklin Pangborn as the art dealer.” And then I had a brainstorm. After I mopped up, I called them and said, “Hey, why don’t we actually do this? A B&W, 1.33:1, authentic-as-possible 1930s two-reeler, like it was one of a series.” They loved the idea. I wrote a script, went on Kickstarter, fell short by a razor-thin 89%, and then broke the two rules of The Producers and paid for it myself. I rounded up a bunch of the Lost Skeleton people, and filled in the remaining slots with some incredible industry vets. We shot for 4 1/4 days in December, and had the cast & crew screening in early March. The first public showing was at Cinefest in Syracuse about two weeks later–which is where you saw it–and now it’s out to festivals. We’re also treating it as a pilot for a potential internet series, since we have titles and loglines for 19 more. I’ve already completed the script for another and started a third. Nick and Will are each writing one as well.

Q8. If It’s a Frame-Up! is successful, what are your plans for the future? (And if it is successful, could you put in a good word for the Dr. Film show? A bad word would be fine, too.)

Well, part of the original intent was to use it as a calling card to raise money for more features for Larry (and me). But as noted above, an internet series would be fine as well. Worst comes to worst, I figure I can make two more, shoot some bridging material, and create an ersatz feature, The Biffle & Shooster Laugh-O-Rama. That at least I could sell to TV and/or make a DVD deal.

Q9. I think this is a stupid question, but it’s been asked too many times for me to ignore it: Why go back and make a cheap, impoverished-looking 1930s short? Shouldn’t you make one that’s BETTER than they were in the 1930s?

I made a cheap, impoverished-looking short because that’s all I could afford to make. If we get any kind of financing, then we’ll do the “earlier, more expensive” ones. And I didn’t make one better than those from the 1930s because NO ONE can.

Q10. I get asked questions by people all the time that aren’t particularly germane or interesting. What question did I NOT ask that I should have asked?

Why does sour cream have an expiration date? Is that when it turns good?

It is part of a global conspiracy. Expired croutons also become fresh bread. Hey, you were warned about stupid jokes, folks.