I’m frequently bombarded with ideas and new concepts. I try to incorporate them in my marketing approach for the Dr. Film show. Since we’ve not (yet) been successful in selling the show, I study people who are successful at marketing to see what they’re doing, and I learn a lot in the process. I thought I’d pass on some of it to you.

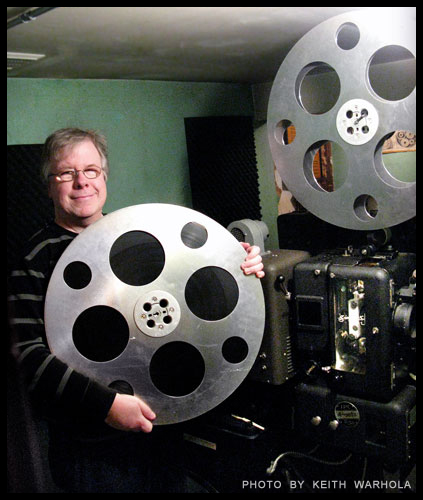

A couple of years ago, I was projecting a film festival, running a bunch of films that were not very interesting. I’m always a sucker for something different and unusual, but I wasn’t finding it on this day, so I had to keep reminding myself that this gig would pay for a big chunk of the month.

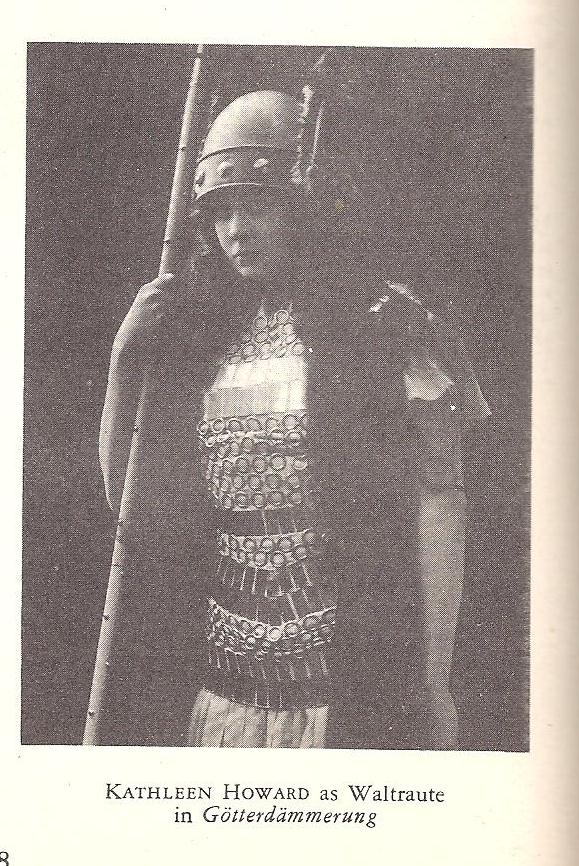

The last film I put on was called Sita Sings the Blues. It delighted me. You want something different and unusual? This was it. A beautiful animated film, using Indian-style art, with music by Annette Hanshaw, a long-forgotten singer from the 1920s and 30s. You wouldn’t think the styles would mesh, but they did, and really well. The art was great, the plot engaging. I loved the picture.

I filed it away in my brain and forgot about it. A while later, I read something that said Sita creator Nina Paley had had trouble licensing the rights to the music. The real soul of that movie is in the songs, and without them, it would ring pretty hollow. Some time later, I heard that a deal had been reached.

I looked on Nina’s website to see what the story was. What I read was quite fascinating. And now, we take a little diversion, but I promise I’ll come back to this.

The most frequent criticism I get about the Dr. Film show is that it should be free on the internet, that it should be a YouTube channel, because only there would it find an audience.

I always have had a problem with this reasoning. I love old films and I love to share them and to tell their stories. But I can’t go around putting stuff on YouTube for free.

As I’ve discussed before, I used to work with a video company, and they released obscure titles on video, films that didn’t survive in pristine form, or films that were a little out of the mainstream. The company did relatively well, well enough that expenses were paid and there was money left at the end of the year. Not much, but some.

Then a company called Alpha Video ordered one copy of everything in the catalog, making bad DVD masters that they sold for $1 at Wal-Mart, a price that no one could compete with.

This one move killed the video business, because there’s no room in the market for a middle-of-the-road distributor. It’s either top of the line, pristine prints (Criterion/Kino), or bargain basement (Alpha Video/archive.org). Releasing films from my collection cost me money, so I stopped. I still love to share movies and save them, but on a more modest level. I do in-person film shows, and they pay better than video releases ever did, if such a thing can be imagined.

But I still keep an eye and ear out for new trends in distribution. The world is changing and doing so at a really fast pace. I realize that the market for Dr. Film is not a large one, so it demands creative marketing, which ain’t my forté.

This is what fascinated me about what Nina was doing. After she reached a settlement with the people representing Annette Hanshaw, she posted Sita Sings the Blues, for free, without commercials. You can, if you choose to, donate money to her to support her new projects. It’s sort of like an online PBS.

The whole “everything is free” nature of the internet just seems to quash any way of making money, and making money is critical here. If Nina wants to make a new film, she has to cover costs and keep her lights on. The time she invests in it means time not being spent on something else that might keep the lights on, so it’s important.

This is a key point that I came to in making Dr. Film. It took me a solid month to edit the single episode we shot. I was lucky at the time because I had no other work going on. Today, I couldn’t do that. I have other work that would prohibit me taking the focused time it would take to cut an episode. This means I’d have to turn down work in order to make the show. Or I’d have to hire someone to help me… ack!

Basically, I can’t do the show for free. It simply costs too much. I either need a grant, or a donation stream, or a paying customer. If I put a 90-minute show up on YouTube, once a month, I’d literally go broke. I could cheapen it and use some of the bad production techniques that mar other YouTube productions, or stick to short clip shows, but I don’t want to do that. It would save editing time by eliminating Anamorphia, but that makes it a lot less fun, too. I want to make a good show, not just a cheap show.

I wondered whether this approach is working for Nina. (Whether it works for Dr. Film is a a different question.) She claims that the approach is working. I emailed her a bit about it, and she seems preoccupied with other work (which is great!), but the bottom line seems promising. It’s covering costs, and that means she’s still working, which is really what we want from an artist, right?

Nina’s page also points to a great site called QuestionCopyright.org. This site is wonderful food for thought… they are advocating for a rethinking of copyright law, which is a great idea. Many are talking about abolishing it, saying that content should be free and that containers (books, CDs, etc) cost money. It’s an interesting thought. Do I wholly endorse it?

No, not entirely. I love the idea, but I remain to be convinced that it’s viable. I live in a world where I’m struggling to keep the lights on and the heat bill paid. I’ve had people copy and freely distribute my work, and I got no credit or money for it.

I’m constantly having to fight against the perception that my work is worthless, so I’m pretty hesitant to set its worth at zero. Sita Sings the Blues is fundamentally different from Dr. Film anyway, because Nina gets to promote her work by showing it at film festivals and such, whereas there’s no real path for me to promote Dr. Film. I honestly think that a free Dr. Film would both get ripped off (the rare films inside it would be redistributed), and it would get almost no viewings because no one knows what it is. A double whammy.

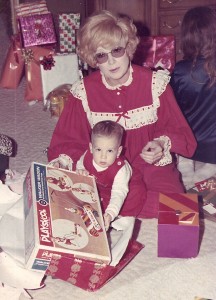

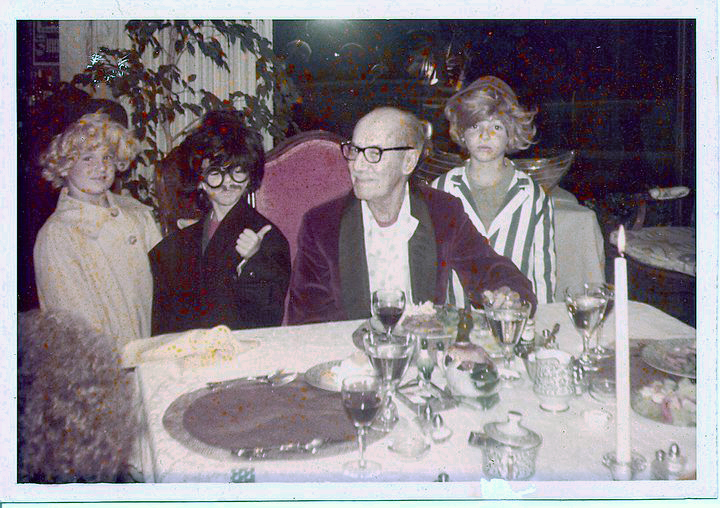

But I’m still crazy. I love old movies. I still save them. I still share them on a more intimate basis. I’m going to go on doing it. You can credit Glory-June Greiff (my long-time co-conspirator and the actress who plays Anamorphia) for keeping the Dr. Film project on the table. She’s adamant that it deserves an audience. I’ve advocated giving up on it for years and she won’t hear of it.

Will Dr. Film be out there for free? You show me a way that I can make them and stay solvent, and I would love to do it. I’ve got a new distributor talking about the show (can’t discuss it yet), and a potential for a distribution deal over local TV if that doesn’t pan out, and a further possibility of some grant money that would allow me to shoot more episodes. The other criticism of the show is that people don’t like the films chosen in the pilot episode. Maybe having a variety of episodes in a package could help sell the idea.

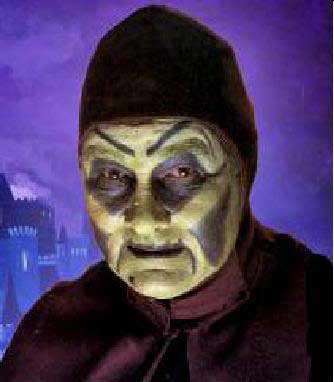

On a different but similar topic.. Penny Dreadful’s Shilling Shockers is more like Dr. Film, and I’ve been studying its distribution system. It’s more of a classic “hosted horror movie” show, without the educational component or the variety of Dr. Film. I really like it. It’s got a lot of heart despite the fact it’s cheap. The only thing I don’t like about it is that they intercut their segments with awful garbage downloaded from archive.org. I’ve come to realize that the main advantage I have with Dr. Film is that I have actual film and a knowledge of what is or isn’t public domain. Penny is getting sponsors and selling DVDs of her shows. It’s not on YouTube, but on local terrestrial TV, a new small-station phenomenon that is growing, along with occasional live streaming episodes. (I would have put some Penny artwork here but there were no pictures on her site that didn’t come with nasty rights warnings, so that has an impact on the kind of plugola I can give her.)

Going forward, I intend to post a 10 Questions With… highlighting one of the people at QuestionCopyright.org. I’d love to get more of their ideas out there. It’s a cool concept, and, again, I advocate copyright reform with every fiber in my being. I may not go as far as they do, but that’s OK.

Will any of this affect Dr. Film? I have no idea. Dr. Film is the show that’s lying on the lab table with an erratic pulse, not quite dead, and not quite alive. These are just some random ideas on trying to jump-start it.